Use of smoked tobacco

Our analysis determined that tobacco was smoked by 13.10% of the middle aged and elderly individuals in India with a rural-urban absolute difference of 7.32%. Among adults aged 15 years and above, GATS 2 found the prevalence of smoked tobacco to be 10.7%. The rural-urban difference determined was 3.6% [21]. The National Non-communicable Disease Monitoring Survey (NNMS) found the prevalence of smoked tobacco to be 12.6%, with the prevalence in rural areas being 1.5% more than urban areas among individuals aged 18–69 years [32].

In our analysis, in rural and urban areas, a higher prevalence of tobacco smokers was found among males, the elderly, Muslims, those from scheduled castes, those with less than a primary school education, those in an unskilled profession, those not living alone and North Indians. In rural areas, the highest prevalence of smoking was among the richer wealth quintiles while in urban areas, the highest prevalence was among the poorest. Previous studies too showed similar determinants of smoked tobacco use [12, 14].

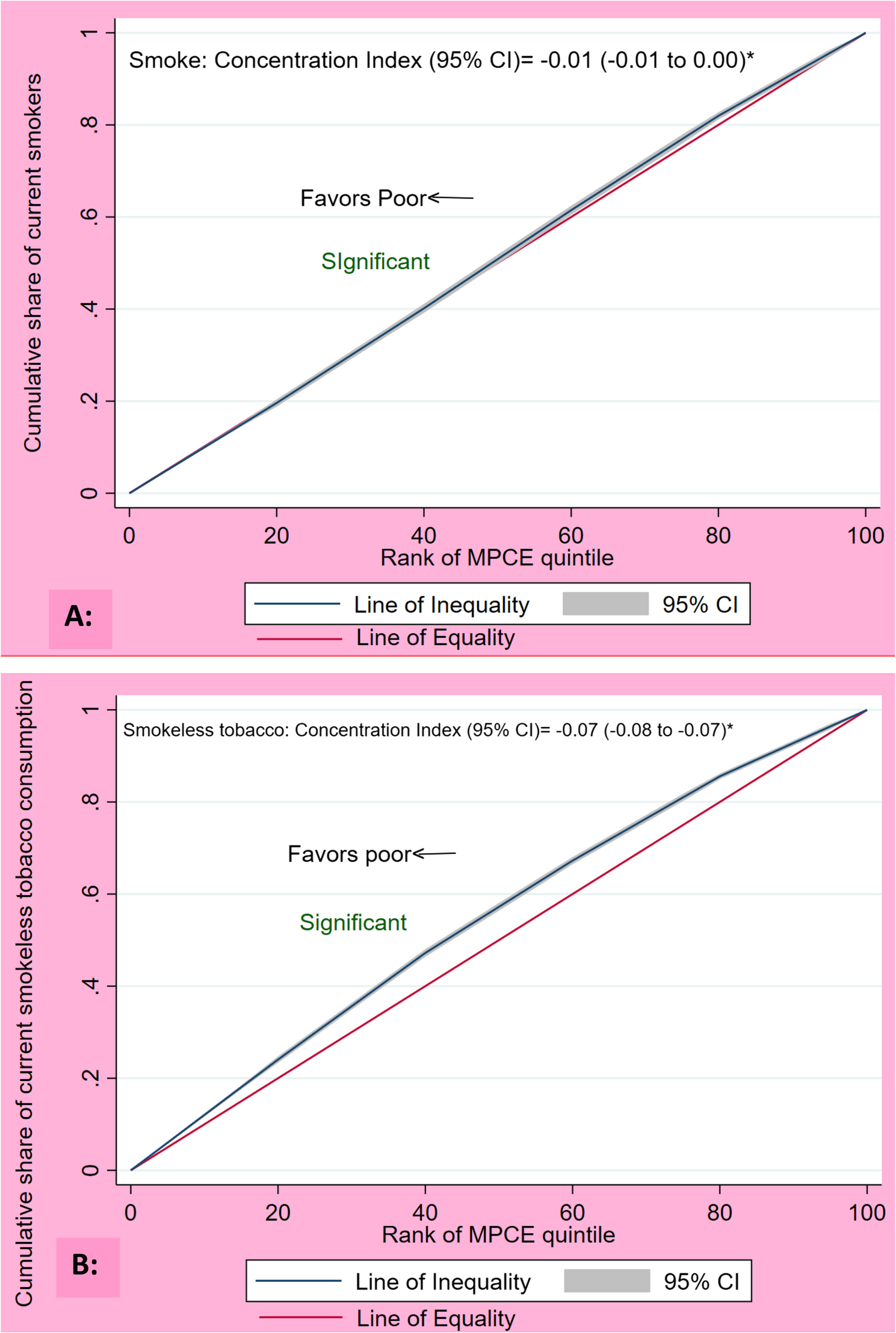

The concentration index of smoked tobacco use showed a slightly higher concentration among the lower wealth quintiles. This is in line with previous literature where the concentration indices calculated for smoked tobacco using data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 5 found a higher concentration among the poor as compared to the rich [33]. A compilation of 4 rounds of NFHS data from 1998 to 2021 found the prevalence of smoked tobacco consumption to be consistently higher among the lowest wealth quintiles [12].

The decomposition analysis of smoked tobacco showed that rural-urban differences in gender composition, educational status and caste were the determinants which contributed the most to the rural-urban difference in the prevalence of smoking. These factors contributed more to the difference in smoked tobacco, than smokeless tobacco, indicating that improving the educational status of the rural population or increasing their sex ratio would decrease the use of smoked tobacco in rural areas more than that of smokeless tobacco.

Gender disparities in smoking can be largely attributed to the socio-cultural beliefs prevalent across India. Among men, smoking is often a communal activity, with practices such as sharing a hukkah viewed as a sign of comradery [27]. It is also perceived as a way to build social connections and is even associated with masculinity. In contrast, women who smoke often face social stigma, as smoking is considered unconventional and inappropriate for women [27, 34]. This social judgment serves as a strong deterrent for women, contributing to the gender gap in smoking prevalence. The situation is changing presently, possibly due to shifting gender roles and changing societal norms [35]. The prevalence of smoking among females has fluctuated minorly since 2005, in contrast to the steep decline among males [36]. This transition may alter the determinants of tobacco use in the future. The prevalence of smoking among rural women is considerably higher than urban women, possibly due to their lower educational status and the prevalent use of inexpensive bidis (traditional hand-rolled cigarettes) [35, 36].

Use of smokeless tobacco

In this analysis, the prevalence of the use of smokeless tobacco in middle aged and elderly Indians was found to be 20.43%, with the rural prevalence being 23.82%, urban prevalence being 13.03% and difference 10.79%. The NNMS determined the prevalence of use of smokeless tobacco to be 24.7%, with a rural (28.3%)-urban (17.6%) difference of almost 10% among individuals 18 to 69 years of age [32]. As per GATS-2, the prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among Indians more than 15 years of age was 21.4%, with a rural prevalence of 24.6%, an urban prevalence of 15.2% and a difference of almost 10% [21].

In our study, the middle aged and elderly individuals with a higher prevalence of smokeless tobacco use as compared to their counterparts were males, Muslims, scheduled tribes, those from the poorer and poorest wealth indices, those with less than a primary education, Northeast Indians, and those who had no media exposure. In rural areas, those with a skilled profession and in urban areas, those with an unskilled profession had higher prevalence of tobacco use. In urban areas, smokeless tobacco use was more among the elderly. A significantly higher concentration of smokeless tobacco users was found among the poor as compared to the rich.

An analysis of GATS 2 data of Indian women found that smokeless tobacco consumption was more among those with lesser education, those from scheduled tribes, those from the poor wealth quintiles and those from Northeast India [17]. An analysis of GATS 2 data by Nair et al. from Northeast Indian states found similar determinants [37]. A decomposition analysis of data from Northeast India found that 90% of the difference in the prevalence of smokeless tobacco use between men and women could be attributed to differences in the age, employment status, education and wealth status [37], emphasising the high contribution of socioeconomic determinants to smokeless tobacco use.

The decomposition analysis showed that differences in the regions of domicile, occupation and education between rural and urban populations contributed the most to the difference in the prevalence of smokeless tobacco use. This re-emphasises the fact that socio-economic factors and regional cultural differences are important determinants of smokeless tobacco consumption.

Smokeless tobacco use is socially accepted in several rural areas of India due to longstanding traditional beliefs and practices [7]. These cultural norms contribute to the wide variation in both the prevalence and types of smokeless tobacco products used across states. In certain eastern and northeastern states, its use remains deeply rooted in local customs [37], and offering betel nut with betel leaf, for instance, is regarded as a sign of hospitality [38]. In these regions, high rates of smokeless tobacco use are also observed among women and youth [17, 39]. In South India, particularly among some indigenous rural tribes, chewing tobacco holds such cultural significance that it is prioritized over food and is commonly used during weddings, festivals, funerals, and even pregnancy [7]. However, studies on tobacco-related beliefs and practices from other states are lacking, highlighting the need for further research to inform culturally tailored interventions.

Policy implications and recommendations

Since the prevalence of smoked and smokeless tobacco consumption was found to be higher in rural areas than urban areas, control efforts should be focussed more there, through cessation programs and strengthened law enforcement. To address the varying prevalence of tobacco use across different states in the country, we propose differential taxing by states, as well as a more decentralized tobacco cessation program design and implementation at the state or regional level. Social and behaviour change communication should be strengthened to address the socio-cultural factors of tobacco use.

In line with previous literature [13], our results emphasise the importance of focussing on the underlying inequities which contribute to differential tobacco consumption. Improving the educational status of the rural population could decrease the difference in the prevalence of smoked tobacco consumption by 41% and smokeless tobacco by 20%. Given the significant negative concentration index, tobacco cessation activities should target poorer wealth quintiles.

The distinct cultural habits and beliefs which have led to regional variations in smokeless tobacco consumption should be explored using qualitative research methods and addressed on an individual basis.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which could be found which delineated the factors contributing to the difference in the rural-urban prevalence of smoked and smokeless tobacco consumption among middle aged and elderly adults in India. The results are generalisable to the population aged 45 years and above in India, given the nationally representative sample included and the appropriate sample weights used.

However, this study has some limitations as well. Given the cross-sectional nature of the primary data-set, temporality could not be determined and there is a chance of reverse-causality. Bonferroni correction was not used while determining the factors associated with tobacco use. Since the data collected was self-reported, there may be underreporting of tobacco use because of social desirability bias. Additional factors which could potentially influence tobacco use, such as knowledge about the toxic effects of tobacco, were not determined for this analysis. The sample chosen for this analysis was middle aged and elderly Indians, due to the lack of data openly available for the entire adult population, which would have made the results more generalisable.