As the number of foreign children living and attending school in Japan grows, the pressure is on to give them the communication skills they need to get their education. But the systems in place for their Japanese language training are falling behind, leaving tens of thousands of kids in situations where they cannot understand their school lessons.

Foreign Families On the Rise

According to the Immigration Services Agency of Japan, the number of foreign nationals living in the country as of the end of 2024 was 3,769,000. This represents an increase of 358,000 from the end of 2023 and is 1.8 times higher than a decade ago.

A particularly fast-growing category is foreigners with the “engineer/specialist in humanities/international services” visa, which includes a wide range of occupations such as technicians, interpreters, designers, language instructors, and more. Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare data shows that the number of foreign workers in this ESHIS category reached 411,000, a 3.9-fold increase in the 10 years leading up to 2024.

ESHIS visa holders are permitted to bring their families to Japan, just like those with visas for work such as university teaching, legal services, and accounting. Naturally, this has led to a rise in the number of foreign children living in Japan. It’s within the context of these structural changes that the urgent need for Japanese language education for foreign children has arisen.

The number of foreign children enrolled in public elementary and junior high schools reached some 129,000 in fiscal 2024, a 9.0% increase from the previous year, according to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT).

The problem is that many schools lack the staff needed to teach JFL, or Japanese as a foreign language, to these children. As a result, more and more children are growing up without sufficient Japanese language skills. Without a shared base in language, which is crucial for communication, their academic and career prospects will be adversely affected and they will tend to be isolated in their communities.

70,000 Children in Need of Japanese Instruction

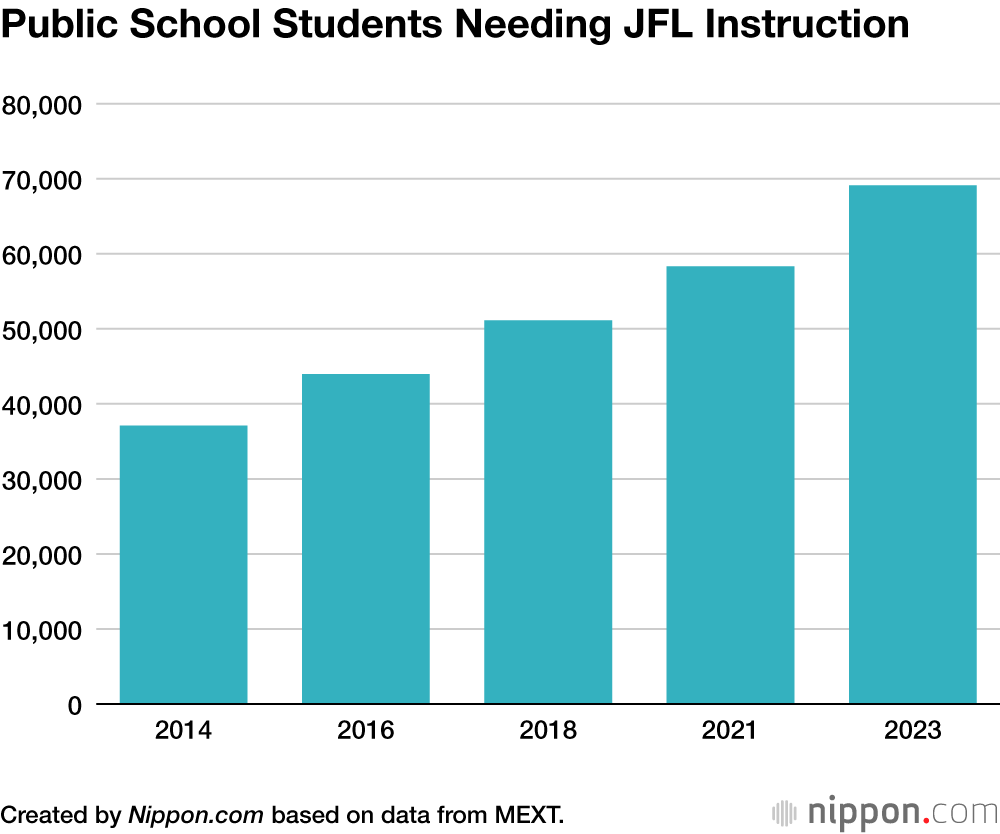

In MEXT’s statistics for fiscal 2023, there were almost 70,000 students that require JFL instruction in public schools, double the number from a decade earlier.

In Matsudo, a city in Chiba Prefecture adjacent to Tokyo, 23,000 of its approximately 500,000 residents as of the end of 2024 were foreign nationals.

To address their needs, the city’s Board of Education set a policy to establish JFL classrooms in elementary schools with at least 18 students requiring instruction in fiscal 2022. As of fiscal 2025, 15 out of the city’s 45 public schools had established these classrooms. From fiscal 2024, a school readiness program was established, where foreign children receive 20 days of intensive instruction before entering school, covering Japanese language essentials for school life such as greetings and reporting health issues. The Board of Education has assigned 33 staff members for this language education and has also secured 37 paid volunteers.

Matsudo’s efforts are relatively comprehensive. In urban parts of Japan, such as the Tokyo metropolitan area and Aichi Prefecture, where there are many students requiring this instruction, it is easier for schools to provide adequate support.

Growing Crisis at Regional Schools

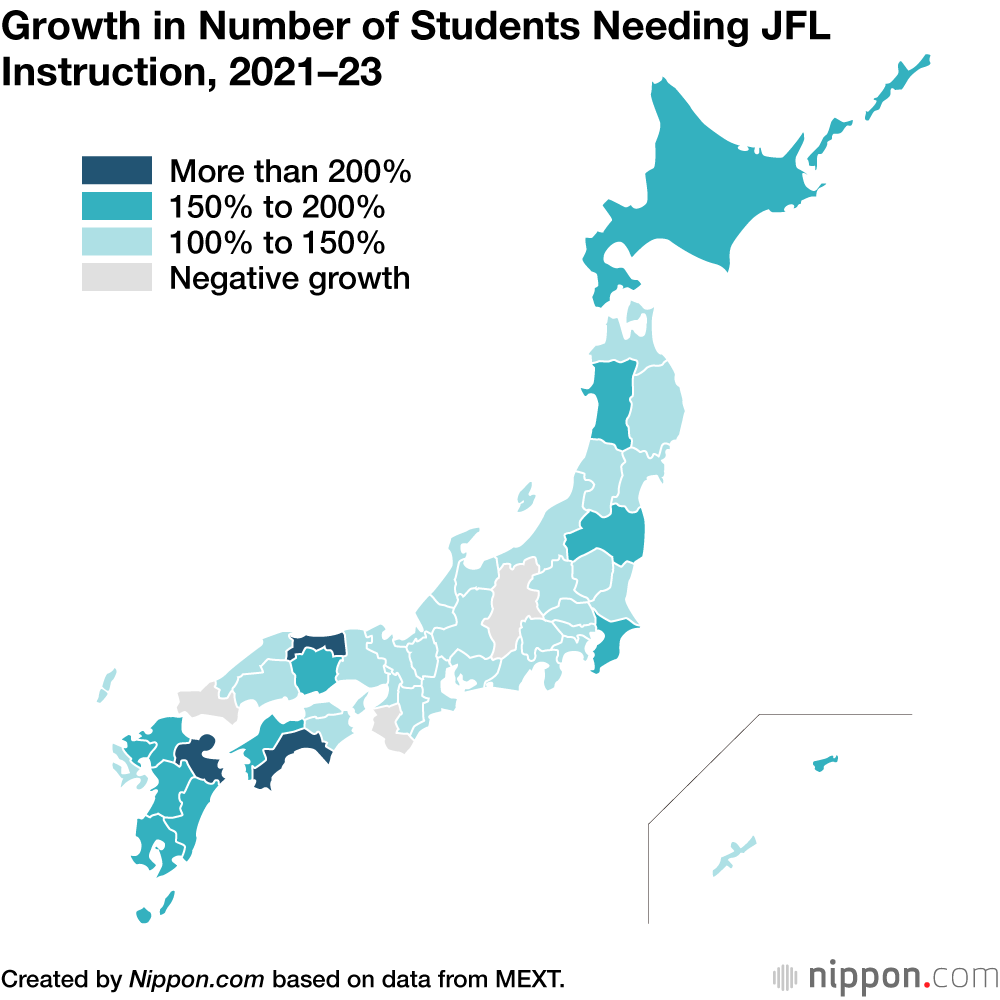

On the other hand, the situation is particularly serious in more rural areas, where foreign children are more thinly dispersed. In terms of the rate of increase of foreign children requiring JFL instruction from 2021 to 2023, Tottori Prefecture was the highest, seeing growth of 2.4 times, from 18 to 44 students. It was followed by Ōita (2.3 times, from 50 to 114), Kōchi (2.3 times, from 12 to 27), Kagoshima (1.9 times, from 28 to 53), and Saga (1.9 times, from 40 to 74). Because the number of foreign children in these areas is much smaller than in urban areas and securing teaching staff is more of a challenge, local governments tend not to have sufficient systems in place.

In fiscal 2023, roughly 30% of public elementary and middle schools across Japan (9,241 schools) had students who needed JFL instruction. According to Wakabayashi Hideki, a visiting associate professor at Utsunomiya University’s School of International Studies who has been involved with the education of foreign children, 70% of these schools had four or fewer foreign children, demonstrating the situation of foreign children being thinly dispersed.

Looking at the breakdown of children requiring JFL instruction by their native tongue, the highest is Portuguese-speaking children, many of whom are of Japanese-Brazilian descent. The number of children native in Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese languages is also rising quickly, and some regions are seeing an increase in those with Nepali and Burmese backgrounds.

“The problem is more likely to go unrecognized when only a few students need support, and municipalities often can’t secure budgets and staff,” says Wakabayashi. “Homeroom teachers and other staff are often left to handle the situation alone. And when students come from multiple linguistic backgrounds, that can make the challenge even greater.”

Many children are unable to keep up with classes taught in Japanese through school instruction alone. That’s why, in urban areas, an increasing number of Japanese language classes are being offered outside of schools by public organizations, NPOs, and local governments to support their learning. By contrast, such programs are often lacking in certain regional areas.

MEXT has issued a Guide for Accepting Foreign Children, and included Japanese instruction in the national curriculum guidelines starting in fiscal 2018. While the government sets staffing standards, it leaves decisions about actual staffing levels and local JFL programs to municipalities, offering mainly subsidies.

The Limits of Keeping It Local

There is also the more fundamental issue of children not attending school. In fiscal 2023, a record 970 foreign children of school age were not enrolled, a 24.6% increase from the previous year. Adding also children whose enrollment status could not be confirmed, MEXT puts the number of such children who may not be attending school at 8,601.

The Constitution of Japan guarantees children the right to receive an education and stipulates that guardians must ensure their children are educated. Legally speaking, this applies only to children with Japanese citizenship, but based on the International Covenants on Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, foreign children are guaranteed the opportunity, if desired, to receive the same education as Japanese children.

Japan’s foreign population is expected to hit 9.39 million in 2070, making up 10% of the nation’s total, according to 2023 projections by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. However, the inflow of foreign nationals is already outpacing these projections, making it likely that the 10% mark will be reached as early as 2050.

“In Japan, there is little awareness of the need to build social infrastructure with the settlement of foreign residents in mind,” says Menju Toshihiro, visiting professor at Kansai University of International Studies. “As a result, the education system for foreign children has largely been left to local governments and individual schools, leading to significant regional disparities. To ensure that foreign children, who will help support Japan’s future, can acquire the same academic abilities as Japanese children, the national government must establish a clear policy and restructure the education system.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)