Earth’s atmosphere is large, extending out to around 10,000 km from the surface of the planet. It’s so large, in fact, that scientists break it into five separate sections, and there’s one particular section that hasn’t got a whole lot of attention due to the difficulty in maintaining any craft there. Planes and balloons can visit the troposphere and stratosphere, the two sections closest to the ground, while satellites can sit in orbit in the thermosphere and exosphere, allowing for a platform for consistent observations. But the mesosphere, the line section in the middle, is too close to have a stable orbit, but too sparse in air for traditional airplanes or balloons to work. As a result, we don’t have a lot of data on it, but it impacts climate and weather forecasting, so scientists have simply had to make a lot of assumptions about what it’s like up there. But a new study from researchers at Harvard and the University of Chicago might have found a way to put stable sensing platforms into the mesosphere, using a novel flight mechanism known as photophoresis.

The mesosphere itself is located between 50 and 85 km up, and while it isn’t technically considered “space” (i.e. it’s not past the Karman line) it is very different from the lower levels of the atmosphere we are more accustomed to. It’s affected both by weather from below and above, reacting to solar storms as often as hurricanes. Since it serves as that kind of interface level, it plays a critical role in how the layers both above and below it react as well.

But we haven’t been able to place any stable monitoring equipment in it due to the difficulty for the two types of continual monitoring systems we have – balloons and satellites. This has led to the moniker “ignorosphere” because scientists have been forced to essentially ignore the existence of this layer of atmosphere due to lack of data.

Graphic showing the location of the photophoresis disc in the atmoshpere compared to satellites and airplanes. Credit – Ben Schafer and Jong-hyoung Kim

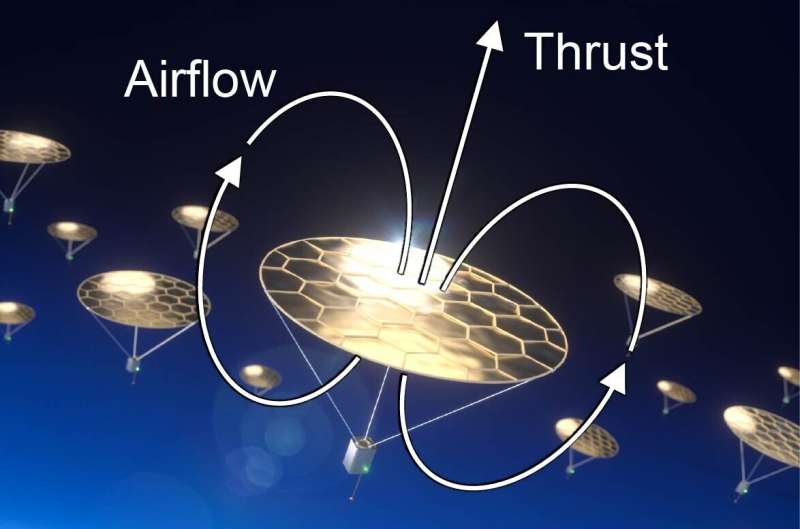

Enter the new paper about long-term sensors in the mesosphere. Photophoresis is a process where more energy is created when gas molecules bounce off the “warm” side of an object than its “cool” side. In this case, the warm side is the side of the object facing the sun while the “cool” side is the underside facing Earth. The effect is only noticeable in low pressure environments, which is exactly what the mesosphere is.

Admittedly the force from photophoresis is miniscule, so the researchers had to develop really tiny parts to have any chance of taking advantage of it. They recruited experts in nanofabrication techniques to make a centimeter scale structure as a proof of concept and tested them in a vacuum chamber designed to have the same pressure as the mesosphere.

The prototypes reacted as expected, and managed to levitate a structure with just 55% of sunlight at a pressure comparable to that of the mesosphere. That marks a first that anyone has ever demonstrated a functional prototype of a photophoresis powered flight, mainly due to how light the structure itself was.

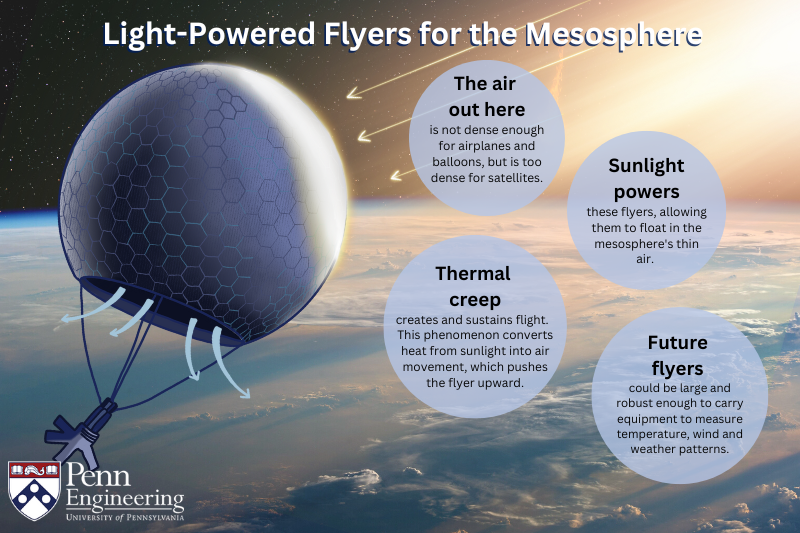

Harvard and Chicago aren’t the only researchers working on photophoresis propulsion – Igor Bargatin’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania received a NIAC grant for a similar concept in 2023. Credit – Melissa Pappas

Harvard and Chicago aren’t the only researchers working on photophoresis propulsion – Igor Bargatin’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania received a NIAC grant for a similar concept in 2023. Credit – Melissa Pappas

Devices powered by this technique could be sent to monitor the mesosphere, but they could also be useful farther afield. Mars is an obvious candidates, since its low pressure and sparse atmosphere are both hallmarks of the planet but also largely unexplored at different layers. Other planets and moons could be potential targets as well – anything that has an atmosphere that is spare enough to support a levitating spacecraft could be served by one of these fliers.

Unfortunately, there’s still some advanced engineering left to do. The nanofabrication technique that was used to build the flight structure didn’t include any functional hardware, such as sensors or wireless communication equipment. A structure that simply floats without transmitting data isn’t scientifically useful, so in order for these devices to start making the type of scientific impact they hope to, the nanofabrication techniques will need to be improved to functionalize the payload they use.

The researchers have no doubt that is possible though, and have already created a start-up company called Rarefied Technologies, which was accepted into the Breakthrough Energy Fellows program last year. With that support, and some ongoing research in nanofabrication, hopefully it will only be a matter of time before we see centimeter-sized sensors scattered throughout the “ignorosphere” and beyond.

Learn More:

Phys.org / Harvard School of Engineering – Sunlight-powered floating structures offer a new window into Earth’s upper atmosphere

B. Schafer et al – Photophoretic flight of perforated structures in near-space conditions

UT – A new Propulsion System Could Levitate Vehicles in the Earth’s Upper Atmosphere

UT – Atmosphere Layers