Kevin Keane,Scotland environment, energy and rural affairs correspondentand

Joanne MacAulay,Reporter

Getty Images

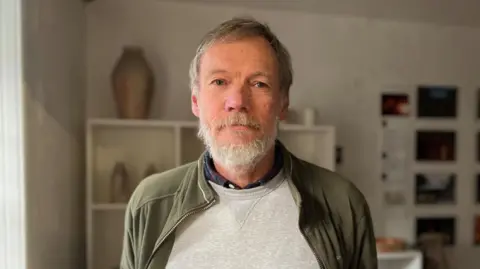

Getty ImagesThe future of nuclear power in Scotland is shaping up to be a battleground at next year’s Holyrood election – and Torness, on the banks of the Forth, is on the frontline.

The Labour government at Westminster has declared its intention to usher in a new “golden age” of nuclear.

But the SNP government at Holyrood opposes new nuclear power stations and can use planning laws to prevent them being built – even though energy policy is reserved to the UK Parliament.

Torness in East Lothian is the last remaining nuclear power station in Scotland.

The imposing building fills the windscreens of drivers heading towards Edinburgh on the A1 and dwarfs Stevenson’s Barns Ness Lighthouse in the next bay.

It is run by EDF Energy and directly employs about 550 workers, with about 180 contractors also based at the site.

During periods of maintenance, that number can swell to above 1,000 – providing a boost to nearby shops, restaurants and hotels.

EDF Energy

EDF EnergyIt provides significant employment to the town of Dunbar, six miles to the west – birthplace of the naturalist John Muir who’s credited with establishing the modern day conservation movement.

But the power plant is due to close in 2030 and there are fears about the impact on the local economy.

Andrea McPherson, 30, grew up in Dunbar and works as an environmental compliance coordinator at Torness.

She says the site makes a positive contribution to the local community.

“With statutory outages, we have about 800 contractors coming onto site for a good eight weeks or longer and they obviously contribute to the local economy (through) lodging, meals, leisure, gyms.”

She also believes that nuclear power has “a lot of future prospects”.

Morag Miller, 32, joined the workforce at Torness a year ago from the oil refinery at Grangemouth, where she had been an apprentice.

She says it is “disappointing” that there’s not going to be a low-carbon alternative employer when the site closes, where displaced oil and gas workers like her could find jobs.

But not everyone in the community is convinced that Dunbar needs new nuclear.

Local potter Philip Revell doesn’t believe “expensive” nuclear should be a part of the energy solution and that decommissioning will provide jobs “for many years to come”.

He added: “Nuclear waste has to be looked after for, in some cases, hundreds of years, which is mind-boggling and nobody’s come up with a solution yet.

“So I think it’s a crazy thing to be doing, to create more waste.”

Earlier this year, the UK government announced its plans to fund new nuclear power plants in England and Wales, including smaller modular reactors (SMRs).

Last month it confirmed that the first of those would be built at Anglesey in North Wales.

Great British Energy Nuclear has been tasked with identifying other potential sites and reporting back to ministers by autumn 2026.

Although energy is reserved to Westminster, Scottish ministers can use planning legislation to prevent new nuclear power stations from being built.

It was the same tactic deployed when the Scottish government blocked fracking for shale gas in 2017.

The government has said it will continue to focus on renewable energy rather than “expensive” new nuclear power.

Its policy was reinforced in a draft energy strategy which was published almost three years ago.

It says Scotland’s future efforts should focus on renewables such as the Berwick Bank wind farm which will be capable of delivering electricity to up to six million homes.

The huge development will sit about 24 miles off the East Lothian coast, with the power coming to shore at Dunbar and Blyth in Northumberland.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUK energy minister, Michael Shanks, said the Scottish government’s “ideological” stance was “the absolutely wrong position to take”.

He added: “Sites like Torness could be where we could site future small modular reactors of the future with the thousands of jobs and apprenticeships that go with it. The SNP’s blocking that.”

The Scottish Energy Secretary Gillian Martin reiterated that Scotland has a policy of no new nuclear reactors.

“Instead, we are focused on supporting the development of Scotland’s immense renewable energy potential – which provide more jobs, are faster to deliver, are safer, and more cost effective than the creation of new nuclear reactors,” she said.

In East Lothian, council leader Norman Hampshire has asked UK ministers to draw up a “characterisation” of the Torness power station site in the hope that it could still be considered for a replacement.

The process would mean commissioning a full independent survey of the site taking into account geological, environmental, infrastructure and community considerations.

Torness closure would be ‘a huge blow’

The Labour councillor says the closure of Torness without a replacement would be devastating to the community in Dunbar and across Scotland.

“There’s a lot of jobs… and all of that feeds into the local economy. So, if Torness isn’t there it’s going to be a huge blow and there’s not the other jobs to replace these jobs here locally,” he said.

“Although we support a lot of renewables here within East Lothian, both onshore and offshore, we know the wind doesn’t blow all the time and when that power drops you need something to back up these turbines. Nuclear is the only baseload that we have available.”

He says the Scottish government’s ban could be lifted if there is a change of power after the Scottish parliament election next year.

And he added: “If we still have a government in Scotland that’s opposed to new nuclear, we will look to challenge that because energy is not a devolved issue.”

‘A range of opportunities’ in renewables

SNP councillor Lyn Jardine, who represents Dunbar, says the main reasons for opposing new nuclear are the delivery time and the costs, as demonstrated by the Hinkley Point C development.

The project, which will be the first new nuclear power station to be built in 30 years, is being delivered five years later than planned and is costing billions more than originally estimated.

Ms Jardine said East Lothian would continue to be an energy generation hub for both Scotland and the UK.

Work is already underway to lay a huge subsea electricity cable from Torness to the north east of England

“If we’re looking for continuity, there’s a quicker way of ensuring that energy is delivered and that’s through renewables in Scotland.

“If you look at what’s going in, in terms of renewables infrastructure, just across the A1, there’s a range of opportunities there.

“I don’t think we need both (renewables) and a new nuclear station,” she added.

EPA

EPAThe Scottish Conservative leader Russell Findlay said in April that the Scottish government’s ban on new nuclear was “bone-headed” and pledged to overturn it with the consent of local communities.

The Scottish Greens say nuclear has “no place in Scotland” while the Scottish Liberal Democrats say developers would need to demonstrate, beyond reasonable doubt, that the new technologies were “effective, safe, clean and value for money.”

Reform UK Scotland has not made an official statement on where it stands on Torness. But UK deputy leader Richard Tice spoke in Parliament a year ago of the “foolishness of relying on wind power” and a need for “more nuclear fast” including small modular reactors.

All of that, and with the continued decline in North Sea oil and gas output, sets us up for a pre-election showdown on the future of Scotland’s energy mix.

Jobs and communities will be at the heart of it but so too will the cost of producing that energy.

The UK has some of the highest energy prices in the world which are placing huge pressure on domestic and business consumers.

It’s a significant contributor to the cost of living crisis and voters will no doubt be looking for guarantees that how Scotland generates its electricity will put money back in their pockets.