September 2025 marked two years since the launch of Indonesia’s carbon exchange, IDX Carbon. After a strong start, the market has slowed, with trading activity now lagging far behind comparable schemes internationally.

IDX Carbon was envisioned as a cornerstone of Indonesia’s climate strategy. Its launch on 26 September 2023 signaled the country’s commitment to join the global shift toward market-based mechanisms for reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and attracting investment.

Globally, carbon markets are booming. According to the World Bank, carbon transactions – including taxes and emission trading systems (ETSs) – generated over USD100 billion in revenue in 2024. In contrast, Indonesia’s contribution remains modest, with total transactions of only IDR78 billion (USD4.9 million) since IDX Carbon became operational. To date, just eight projects have been listed, and only 132 participants are registered to trade.

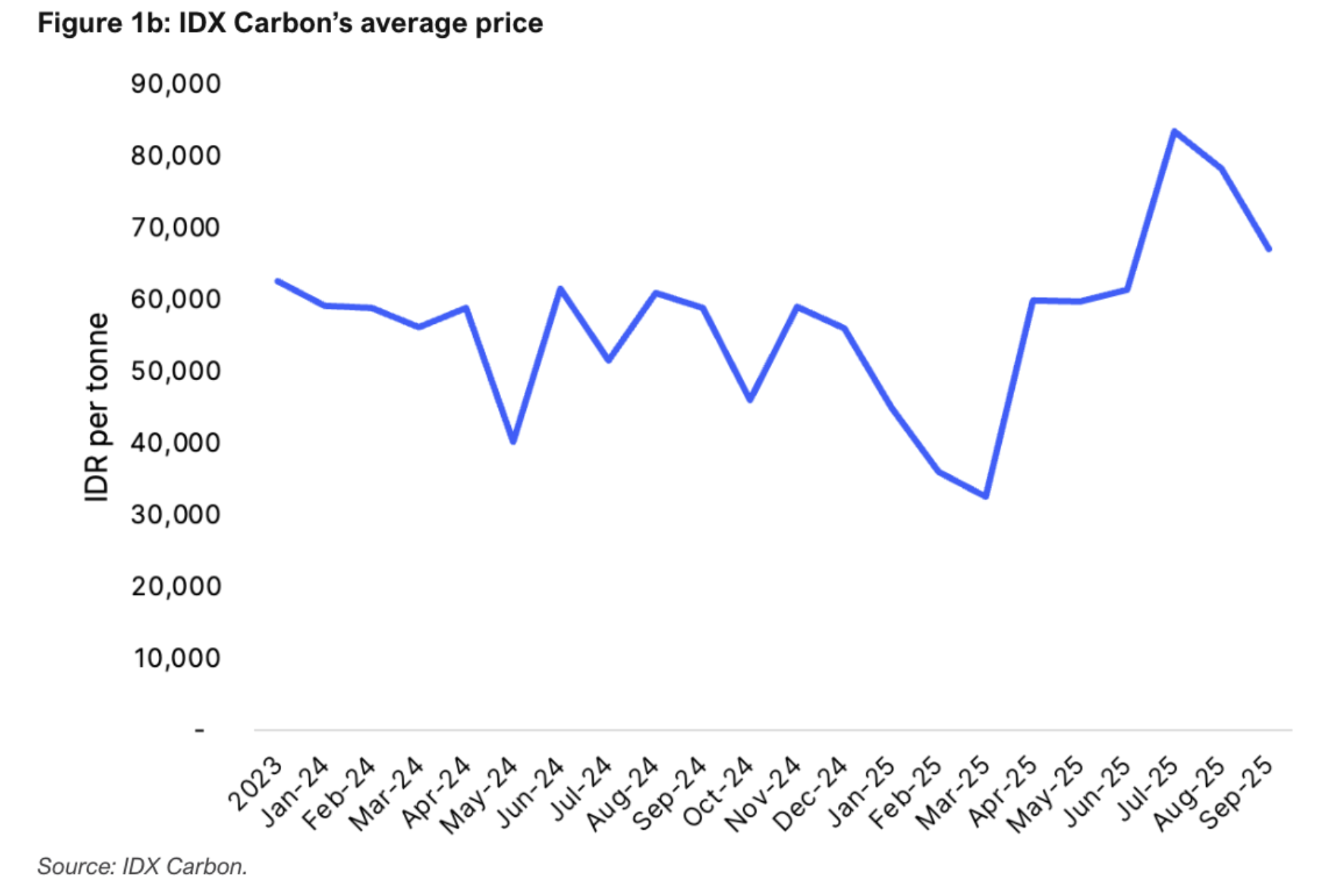

The performance of IDX Carbon has not met expectations, particularly given its promising start in 2023. In the final three months of that year alone, the market recorded transaction values of IDR31 billion (USD2 million) and a trading volume of 494,254 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). Following that early momentum, however, the market has shown a steady downward trend.

The average carbon price dropped from IDR62,533 (USD4.1) per tonne in 2023 to IDR55,985 (USD3.9) per tonne in December 2024, with no transactions recorded in February 2024. The trade value fell to just IDR20 billion, with a reduced trade volume of 413,764 tCO2e and only three projects listed. A brief surge occurred in October 2024, coinciding with the inauguration of President Prabowo Subianto’s administration and following the government’s plan to establish a Climate Change Management and Carbon Trading Agency (BP3I-TNK), when trade reached a peak of IDR13 billion (USD0.9 million). However, this proved short-lived, as activity declined again in the final months of the year. In other words, while new markets initially tend to grow after establishment, the Indonesian carbon market has shrunk.

At the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) climate summit in Baku, Indonesia played a prominent role in advancing discussions on carbon trading, aiming to generate additional revenue and attract foreign investment through the sale of carbon credits. Before the summit, Indonesia and Norway had also made significant progress in strengthening international climate cooperation under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. A notable development at COP29 was the signing of a Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA) by Indonesia and Japan for bilateral carbon credit trading — the first of its kind under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement.

Following COP29, Indonesia opened IDX Carbon to international buyers in January 2025, signaling a strategic shift toward global integration. The move sparked renewed market activity, reflecting heightened investor interest. However, despite initial increases corresponding to the announcement, overall activity has been minimal and covers only a small portion of Indonesia’s emissions. From March to September 2025, the total transaction value fell to just IDR1 billion (USD72,621), with a modest trade volume of 27,613 tCO2e. As of September, the average carbon price was IDR67,047 per tonne (approximately USD4), with eight projects listed and 132 registered participants. The cumulative volume of the retired carbons reached 600,768 tCO2e.

By comparison, Japan’s GX-ETS started in 2024 as a voluntary scheme and already has over 700 participants, covering nearly 50% of national emissions. Participation is likely to increase as it becomes mandatory in 2026. The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the world’s most robust carbon market, with over 11,000 participants and an average carbon price of USD70. It covers more than 40% of the EU’s total emissions.

Why is Indonesia’s carbon market stagnant?

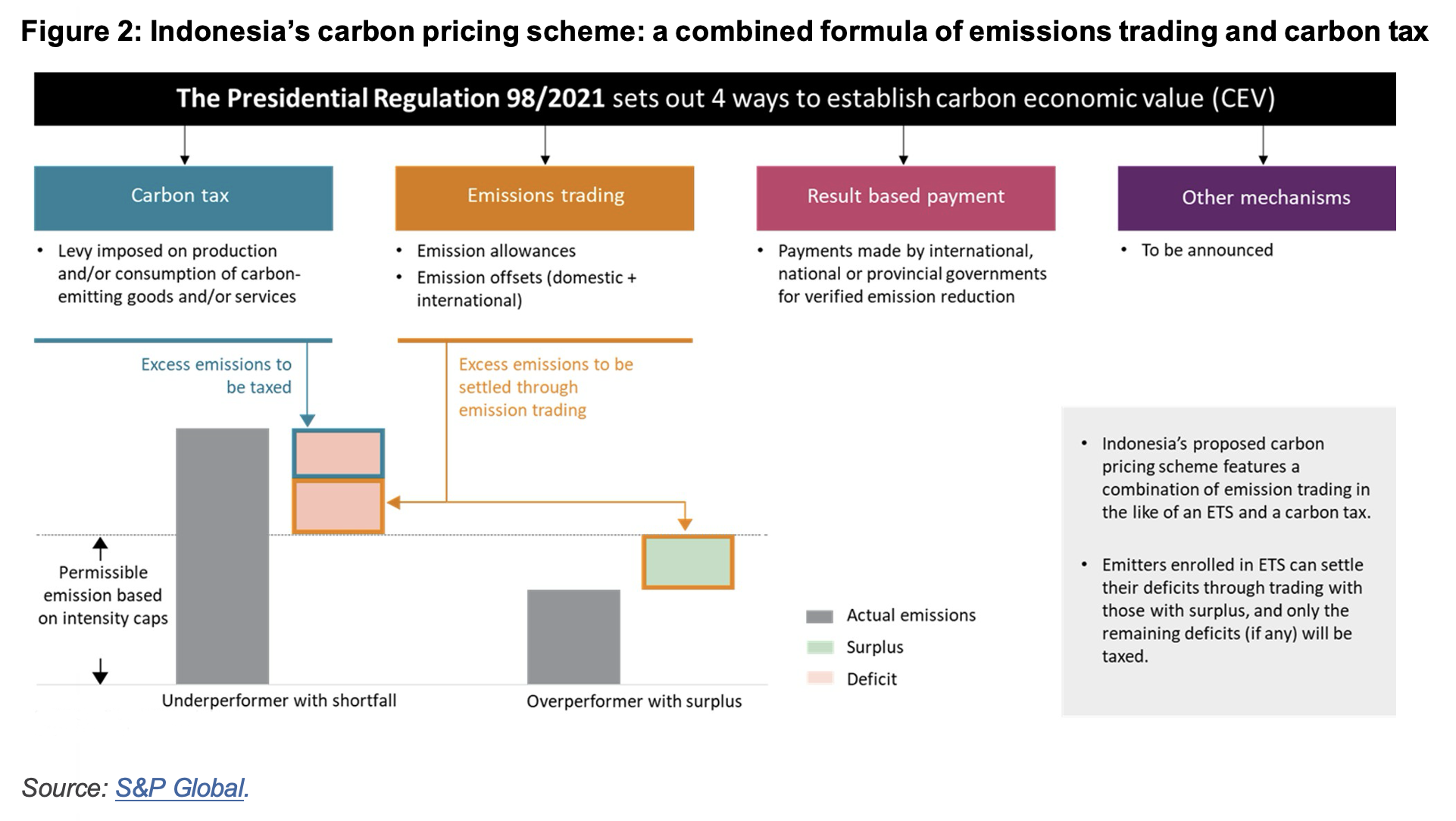

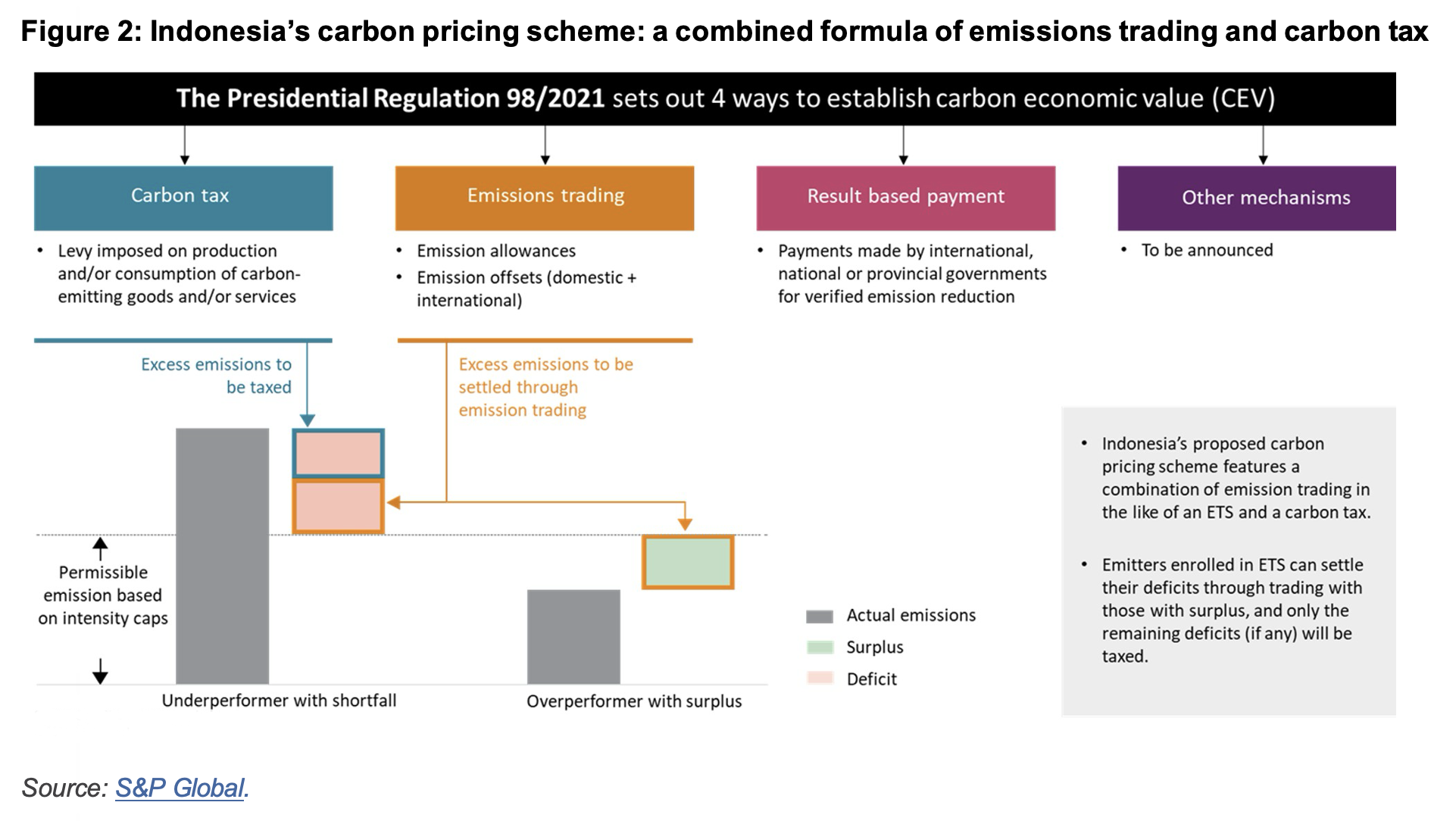

The stagnation in Indonesia’s carbon market can be traced to several underlying factors. Fundamentally, the system is a hybrid carbon pricing strategy that blends a cap-and-trade mechanism with a fallback carbon tax. Under the cap-and-trade mechanism, emitters are assigned sectoral caps (PTBAE-PU). Those operating below their cap earn emissions reduction certificates (SPE-GRK), while those exceeding it must either purchase these credits or pay a carbon tax if credits are unavailable.

In theory, this structure offers both flexibility and fiscal discipline. However, in practice, it has been constrained by design flaws and political caution.

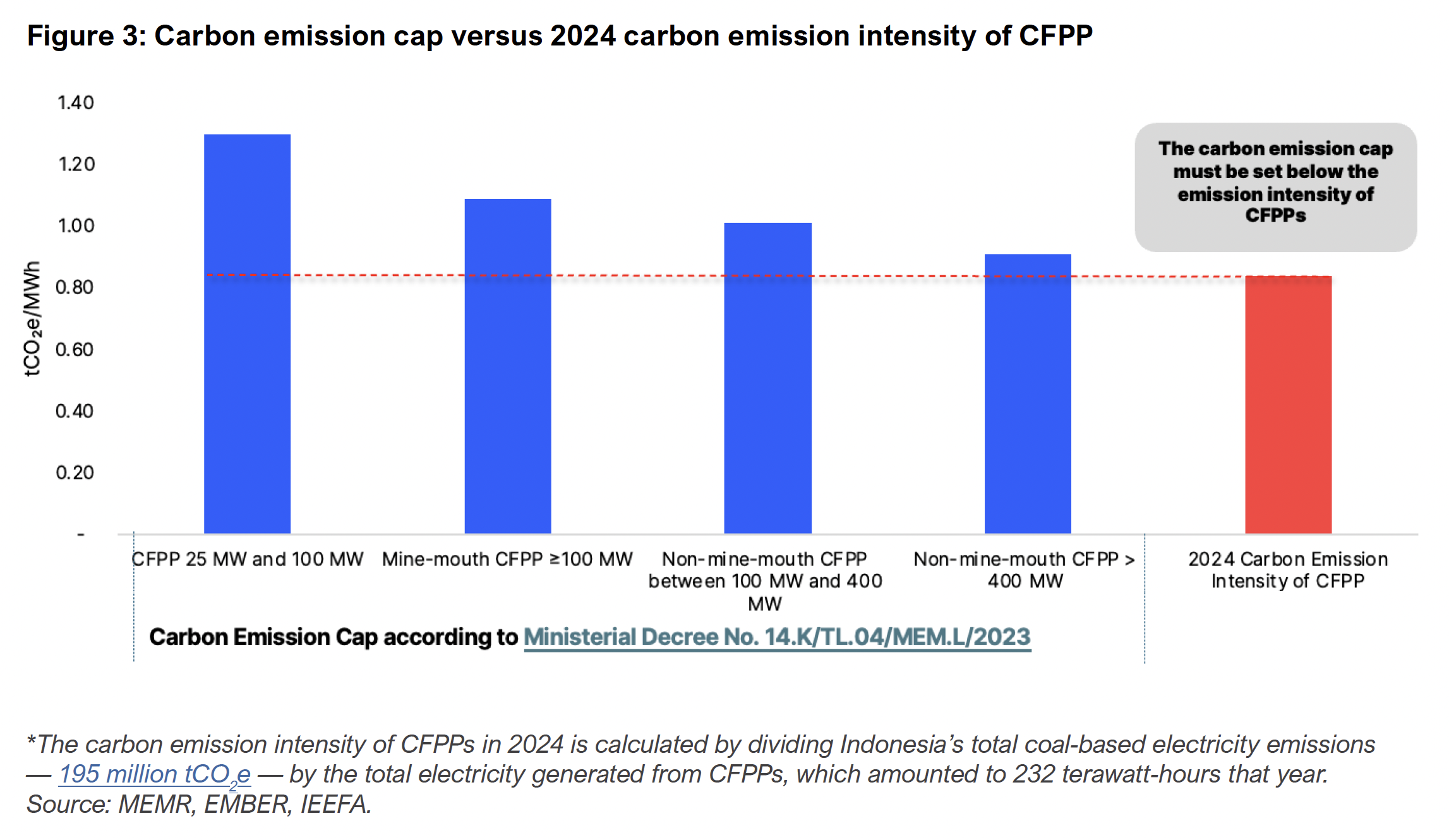

Currently, the carbon market is limited to coal-fired power plants (CFPPs), with 245 registered participants and a combined installed capacity of 54 gigawatts. The sectoral caps are defined in Ministerial Decree No. 14.K/TL.04/MEM.L/2023, which establishes differentiated emission thresholds based on plant type and capacity. For CFPPs with capacities between 25 and 100 megawatts (MW), the cap is 1.297 tCO2e per megawatt-hour (MWh). Mine-mouth CFPPs of 100MW or above face a lower cap of 1.089 tCO2e/MWh. Non-mine-mouth CFPPs between 100MW and 400MW must comply with a cap of 1.011 tCO2e/MWh, while the most stringent cap, 0.911 tCO2e/MWh, applies to non-mine-mouth CFPPs above 400MW.

Despite this structure, the emission thresholds are set so high that only a small fraction of facilities exceed them, resulting in minimal demand for credits or tax payments. This weakens incentives for emission reduction and trade participation.

Exacerbating the issue, the carbon tax (outlined in the 2021 Tax Harmonization Law and Presidential Regulation 98/2021 [PR 98/2021]) remains undefined and unenforced. Although an initial rate of IDR30,000/tCO2e (approximately USD2/tCO2e) has been proposed, implementation has been delayed due to challenges in measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV), as well as political resistance and industry pushback.

Beyond technical design, the development of Indonesia’s carbon market is also restricted by unclear trading and certification procedures. While PR 98/2021 provides the legal basis for carbon pricing, implementation is hindered by overlapping mandates across ministries and a lack of efficient licensing and certification processes.

To address these challenges, the government issued Presidential Regulation No. 110/2025 (PR 110/2025), which aims to introduce a transparent governance framework and foster cross-ministerial collaboration. PR 110/2025 builds upon PR 98/2021 and outlines a more comprehensive structure for Indonesia’s carbon governance, aligned with international climate commitments and domestic green economy goals.

There are several key additions in PR 110/2025:

- Introduction of carbon allocations

These carbon allocations serve as a strategic planning tool aligned with national low-carbon development and green economy goals. The allocation process involves coordination across multiple ministries, including forestry, environment, energy, industry, agriculture, finance, and national planning, and forms the basis for preparing and determining Indonesia’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). - Introduction of ministerial authorization and corresponding adjustment

Entities will be allowed to use carbon units to fulfill other countries’ NDCs, meet international mitigation obligations, or serve other global interests. PR 110/2025 incorporates the concept of corresponding adjustment, in line with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) guidelines, to ensure transparency and avoid miscounting. - Refined carbon trading framework

The updated carbon trading framework distinguishes between domestic and international trading. International transactions are categorized based on whether they require authorization and corresponding adjustment, particularly those linked to NDCs and Paris Agreement compliance, or are voluntary and not tied to international obligations. - Strengthened transparency mechanisms

The updated framework expands on the previous one and clearly outlines steps for obtaining SPE-GRK certification, which can serve as a basis for accessing green and sustainable financing instruments. - Formation of a cross-ministerial dedicated committee

Notably, the new regulation proposes a dedicated committee, led by the Coordinating Minister for Food Affairs, with representatives from relevant ministries. This shift aims to foster a more integrated and strategic approach to developing the carbon market.

Overall, PR 110/2025 provides a more integrated, accountable, and internationally aligned framework. However, its effectiveness will depend on timely implementation, continuous monitoring, and rigorous evaluation to ensure it delivers the necessary support and institutional clarity for a robust carbon market. Simultaneously, strategic reforms will also be essential.

Strategic reforms to unlock Indonesia’s carbon market potential

Carbon pricing offers a powerful tool that helps countries reduce emissions, while mobilizing revenue, boosting innovation, and attracting global investment. For Indonesia, the opportunity is especially significant. The country holds substantial potential to lead global climate action through nature-based solutions and renewable energy.

Home to the world’s third-largest tropical rainforests (125.9 million hectares), Indonesia can theoretically absorb up to 25.18 billion tonnes of CO2. Its mangrove forests, spanning 3.31 million hectares, store around 33 billion tonnes of carbon, while its 7.5 million hectares of peatlands hold an estimated 55 billion tonnes. Collectively, Indonesia’s ecosystems have the capacity to absorb over 113 billion tonnes of CO2, positioning the country as a key player in the global carbon market.

Beyond nature-based assets, Indonesia’s renewable energy advantages are equally noteworthy, potentially translating to an annual emission reduction of up to 27.5 billion tonnes of CO2e. However, carbon prices currently remain below USD20 per tCO2e, far short of the USD50–USD100/tCO2e needed by 2030 to meet climate goals. A carbon market established to monetize assets rather than reduce emissions could undermine the rationale for carbon prices.

Several strategic reforms are needed to enable Indonesia to actively benefit from the carbon market:

- Robust caps and tax rates

Effective carbon caps with clearly defined downward limits should be implemented and supported by more robust taxes. The current caps on carbon emissions need to be lowered and gradually tightened over time to reflect the urgency of climate goals, as can be seen in the EU ETS’s Fit for 55 climate package. One key change needed is a faster reduction in the emissions cap, which limits the total amount of carbon allowances available to industries. To reinforce these limits, carbon taxes on emissions that exceed the caps must be substantial enough to influence industry behavior. - Transparent regulations

Indonesia should establish comprehensive regulations and standards to ensure transparency and accountability. Although IDX Carbon is open to international buyers and offers a relatively low price, the projects available still lack international certification, making them less attractive to global investors. The recent announcement that Indonesia has signed an MRA with Verra, one of the world’s leading standard setters for climate action and sustainable development, marks a pivotal step forward. However, building trust among buyers and investors in Indonesia’s carbon credits, particularly regarding transparency, remains a persistent challenge. - Market reforms

Any carbon tax should be implemented in combination with market reforms. The impact of a carbon tax would be most significant for the energy and industrial sectors, which remain heavily reliant on CFPPs. Given the potential impact on energy prices and industrial competitiveness, the government must engage stakeholders across sectors to design a socially and economically viable approach. - Low-carbon transition pathway

Along with caps and taxes, there needs to be a viable path to access decarbonized energy and incentives to invest in lower-carbon industrial processes. The insignificant supply of renewable energy certificates available illustrates the challenges facing a zero-carbon transition. Currently, access to clean energy is under the control of the national electric utility, PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN). If PLN is unable to invest in clean energy supplies quickly and cost-effectively, the government should create pathways for the private sector to develop renewable energy. Introducing regulations to enable open access to the transmission grid, as previously highlighted by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), would significantly advance this objective. -

Certification and monitoring

Robust certification guidelines and monitoring systems are essential. The government’s plan to establish a dedicated agency for carbon market governance is an opportune innovation and should be fast-tracked. A centralized body could streamline the MRV process (especially certification procedures), improve enforcement, and enhance investor confidence. However, success will depend on strong inter-ministerial coordination, particularly among the Ministries of Forestry, Environment, Energy and Mineral Resources, and Finance.Measurement standards should be established to facilitate robust and credible data collection. For the power and industrial sectors, consideration might be given to requiring automated emissions monitoring, supported by auditable reporting.

- Institutional strengthening

Reinforcing the institutional capacity of IDX Carbon is essential. Carbon markets are inherently vulnerable to fraud due to the intangible nature of the assets traded. Weak oversight, poor credit integrity, and a lack of transparency have led to controversy in other countries. The government should strengthen IDX Carbon by enforcing rigorous standards for credit issuance, verification, and trading.

Towards a net-zero future

With President Prabowo emphasizing a clear vision for net-zero emissions by 2060 or earlier, the urgency to build a credible and functional carbon market has never been greater. A gradually declining emissions cap, aligned with climate goals, would send strong price signals, incentivize low-carbon investments, and accelerate sectoral transformation.

By balancing domestic priorities with phased international integration, Indonesia can unlock climate finance, enhance energy security, and position itself as a regional leader in carbon governance. If implemented effectively, the country’s hybrid model could serve as a blueprint for emerging economies seeking to reconcile development goals with climate ambitions.

Read the summary in Bahasa here: Dua Tahun Berjalan, Pasar Karbon Indonesia Stagnan dan Sepi Peminat