A landmark UK Biobank study reveals that not all additives are equal: while sugars, sweeteners, and flavorings drive higher mortality, gelling agents may offer protection, reshaping how we view the risks of ultra-processed foods.

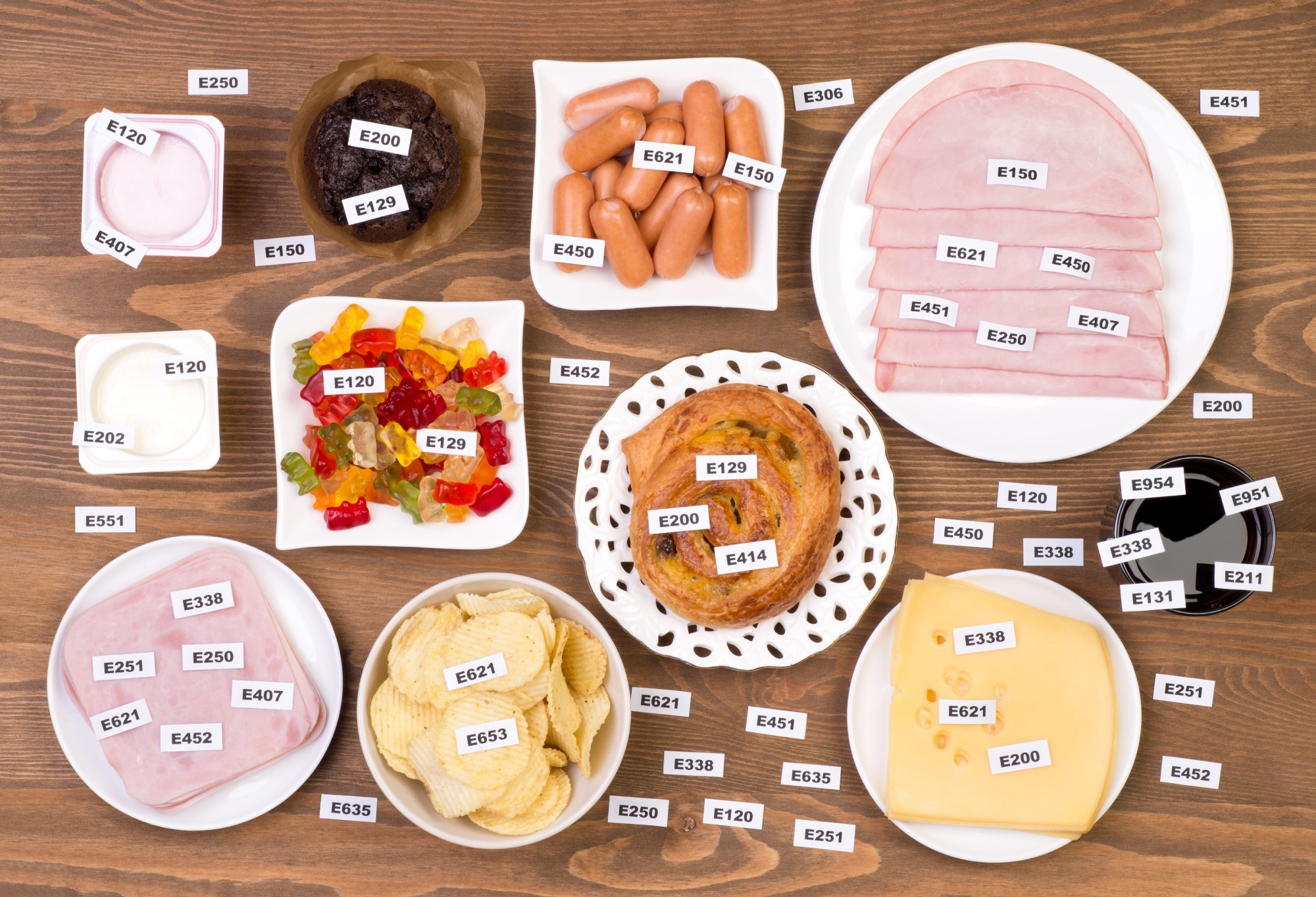

Study: Association of 37 markers of ultra-processing with all-cause mortality: a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Image Credit: photka / Shutterstock

In a recent article in the journal eClinicalMedicine, researchers in Germany investigated whether specific markers of ultra-processing (MUPs) are associated with mortality, beyond the established links between ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and poor health.

Their findings indicate that certain types of sugar, sweeteners, coloring agents, flavor enhancers, and flavors were associated with a higher risk of mortality, as was overall UPF intake.

Background

UPFs are highly industrially processed items that are typically rich in fat, sugar, and salt but low in nutrients such as fiber, protein, and vitamins. These foods are marketed aggressively and valued for their convenience, often replacing healthier dietary options.

The consumption of UPFs has been rising globally, with countries such as the UK and the USA deriving more than 50% of their total energy intake from them, compared with around 10% in Italy.

This trend is concerning, as UPFs have consistently been associated with obesity, weight gain, and numerous negative health outcomes. Consequently, several national dietary guidelines recommend limiting UPF intake.

Food processing is commonly classified using the NOVA system, which categorizes foods into four groups. UPFs fall under NOVA group 4 and can be identified through MUPs. These include cosmetic additives such as sweeteners, flavors, and colors, as well as non-culinary ingredients like modified oils or fructose.

A food is classified as UPF if it contains at least one MUP. Although UPFs have been strongly linked to mortality, no studies have directly examined whether specific MUPs contribute equally to these risks. This knowledge gap is critical, as certain additives may lead to negative health outcomes, while others may not.

About the study

Researchers used data from the UK Biobank, a large prospective cohort study of over 500,000 adults recruited between 2006 and 2010.

For this study, 186,744 participants aged 40–75 years were included after applying exclusions for missing information, implausible dietary reports, and pre-existing health conditions such as diabetes or malabsorption disorders. Dietary intake was assessed using up to five 24-hour web-based food recalls completed per participant.

To estimate UPF and MUP consumption, researchers matched each food item reported to up to ten commercial products from UK supermarkets. Ingredient lists were analyzed for 57 possible MUPs grouped into nine categories, with 37 of these found in at least one product. For each food item, a Marker Likelihood Index (MLI) was calculated based on the proportion of commercial products containing a specific MUP.

The proportion of intake from UPFs or specific MUPs for each participant was calculated relative to total food intake (expressed as a percentage of total food intake, %TFI).

Mortality data were obtained from national health registries, with follow-up until December 2022 (mean follow-up 11.0 years).

Statistical analyses used Cox proportional hazard regression models with penalized cubic splines to examine associations between MUP intake and all-cause mortality, adjusting for age, alcohol intake, BMI, ethnicity, health status, education, psychiatric history, income, physical activity, blood pressure, sex, smoking, and socioeconomic deprivation. Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the findings.

Key findings

The participants were 58 years old on average, and 57% were female; UPF intake accounted for an average of 20.0% of their total food intake. Over 11 years of follow-up, 10,203 deaths occurred. Higher UPF consumption was significantly associated with increased all-cause mortality, with the lowest risk (HR-nadir) at 18% TFI and risk rising beyond that intake level.

When examining specific MUPs, five categories – flavour, flavour enhancers, colouring agents, sweeteners, and varieties of sugar – showed strong positive associations with mortality risk at specific intake levels:

- Flavour: HR-nadir at 10% TFI, with 40% TFI vs 10% TFI showing HR=1.20

- Flavour enhancers: HR-nadir at 0% TFI, with 2% TFI vs 0% TFI showing HR=1.07

- Colouring agents: HR-nadir at 3% TFI, with 20% TFI vs 3% TFI showing HR=1.24

- Sweeteners: HR-nadir at 0% TFI, with 20% TFI vs 0% TFI showing HR=1.14

- Varieties of sugar: HR-nadir at 4% TFI, with 10% TFI vs 4% TFI showing HR=1.10

In contrast, no associations were observed for processing aids, modified oils, protein sources, or fibre.

At the individual level, 13 specific MUPs were significantly related to mortality. These included glutamate and ribonucleotides (flavor enhancers); acesulfame, saccharin, and sucralose (sweeteners); caking agents, firming agents, thickeners (processing aids); and fructose, inverted sugar, lactose, and maltodextrin (sugars). Notably, gelling agents (processing aids) showed an inverse association with mortality risk. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of results, especially for UPF, flavour, coloring agents, and sweeteners.

Conclusions

This exploratory study is the first to assess broad categories and specific MUPs in relation to mortality, showing associations between higher mortality risk and both overall UPF intake as well as several MUPs (flavors, flavor enhancers, coloring agents, sweeteners, and sugars).

The findings are consistent with mechanistic evidence linking these additives to weight gain, metabolic disruption, and alterations in gut microbiota. The inverse association for gelling agents (possibly due to pectin content) highlights significant variation in health effects across additives.

Strengths include the large cohort size, extended follow-up, and novel MUP-based classification using commercial product analysis, which enhances objectivity compared with predefined UPF food lists. However, as an exploratory analysis, limitations include reliance on self-reported dietary data, potential residual confounding, limited power for rarer MUPs, and the ‘healthy volunteer’ bias of the UK Biobank.

These results highlight specific MUPs, such as flavorings, colorings, sweeteners, certain processing aids (e.g., thickeners), and sugars, as potential drivers of UPF-related health risks. Replication and exploration of mechanisms in future research are needed.