Fossils uncovered in northeastern Ethiopia, dating to between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago, provide new insights into the course of human evolution.

An international team of researchers has uncovered new fossils in Africa showing that Australopithecus and the earliest known members of Homo lived in the same region at the same time, between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago. Among the finds was a previously unknown species of Australopithecus, unlike any identified before.

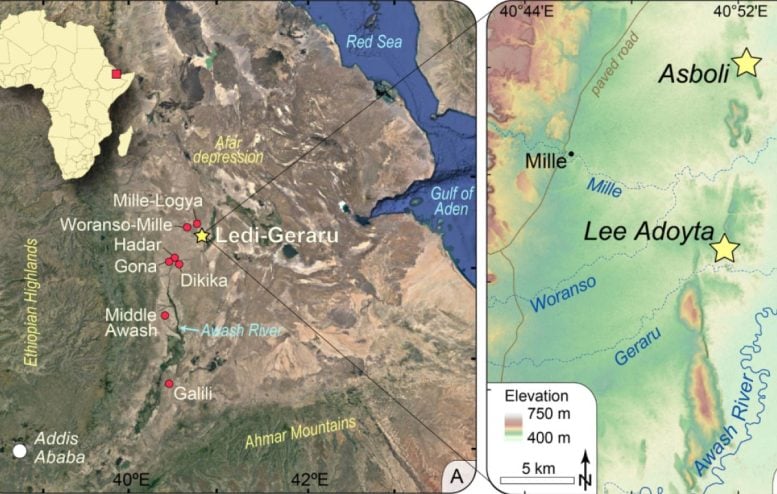

The discoveries come from the Ledi-Geraru Research Project, led by scientists at Arizona State University. This site has already produced the world’s oldest known Homo specimen, as well as the earliest examples of Oldowan stone tools.

Detailed study of the newly recovered Australopithecus teeth confirmed that they represent a distinct species rather than belonging to Australopithecus afarensis, the species of the famous fossil “Lucy.” This finding reinforces that no remains of Lucy’s lineage are known to be younger than 2.95 million years.

“This new research shows that the image many of us have in our minds of an ape to a Neanderthal to a modern human is not correct — evolution doesn’t work like that,” said ASU paleoecologist Kaye Reed. “Here we have two hominin species that are together. And human evolution is not linear, it’s a bushy tree, there are life forms that go extinct.”

A research effort spanning decades

Reed serves as a Research Scientist at the Institute of Human Origins and is a President’s Professor Emerita in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University. She has also co-directed the Ledi-Geraru Research Project since 2002.

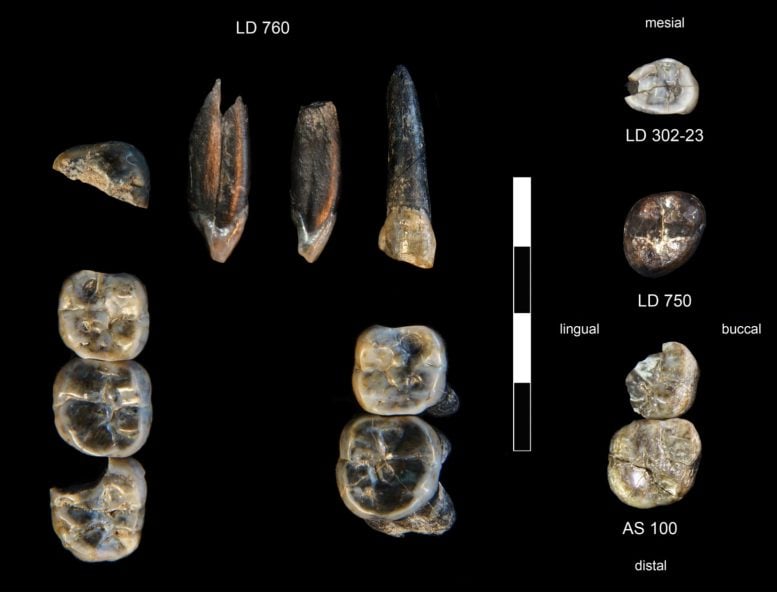

So what fossils helped shape these new conclusions? The team uncovered 13 teeth in total.

The Ledi-Geraru site has drawn attention before. In 2013, Reed and her colleagues reported the discovery of the earliest known Homo fossil—a jaw dating to 2.8 million years ago. The new study builds on that legacy, describing additional teeth from the site that belong to both the genus Homo and a newly identified species of Australopithecus.

“The new finds of Homo teeth from 2.6 – 2.8 million-year-old sediments, reported in this paper, confirm the antiquity of our lineage,” said Brian Villmoare, lead author and ASU alumnus.

“We know what the teeth and mandible of the earliest Homo look like, but that’s it. This emphasizes the critical importance of finding additional fossils to understand the differences between Australopithecus and Homo, and potentially how they were able to overlap in the fossil record at the same location.”

The team cannot name the species yet based on the teeth alone; more fossils are needed before that can happen.

How do scientists know these fossil teeth are millions of years old?

Volcanoes.

The Afar region remains an active rift zone, marked by frequent volcanic and tectonic activity. When these volcanoes erupted, they released ash containing crystals known as feldspars, which provide scientists with a way to determine their age, explained Christopher Campisano, a geologist at ASU.

“We can date the eruptions that were happening on the landscape when they’re deposited,” said Campisano, a Research Scientist at the Institute of Human Origins and Associate Professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

“And we know that these fossils are interbed between those eruptions, so we can date units above and below the fossils. We are dating the volcanic ash of the eruptions that were happening while they were on the landscape.”

Ledi-Geraru’s ancient landscape

Finding fossils and dating the landscape not only helps scientists understand the species, but it also helps them recreate the environment millions of years ago. The modern faulted badlands of Ledi-Geraru, where the fossils were found, are a stark contrast to the landscape these hominins traversed 2.6 – 2.8 million years ago. Back then, rivers migrated across a vegetated landscape into shallow lakes that expanded and contracted over time.

Ramon Arrowsmith, a geologist at ASU, has been working with the Ledi-Geraru Research Project since 2002. He explained the area has an interpretable geologic record with good age control for the geologic time range of 2.3 to 2.95 million years ago.

“It is a critical time period for human evolution as this new paper shows,” said Arrowsmith, professor at the School of Earth and Space Exploration. “The geology gives us the age and characteristics of the sedimentary deposits containing the fossils. It is essential for age control.”

Reed said the team is examining tooth enamel now to find out what they can about what these species were eating. There are still remaining questions the team will continue to work on.

Were the early Homo and this unidentified species of Australopithecus eating the same things? Were they fighting for or sharing resources? Did they pass each other daily? Who were the ancestors of these species?

No one knows – yet.

“Whenever you have an exciting discovery, if you’re a paleontologist, you always know that you need more information,” said Reed. “You need more fossils. That’s why it’s an important field to train people in and for people to go out and find their own sites and find places that we haven’t found fossils yet.”

“More fossils will help us tell the story of what happened to our ancestors a long time ago — but because we’re the survivors, we know that it happened to us.”

Reference: “New discoveries of Australopithecus and Homo from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia” by Brian Villmoare, Lucas K. Delezene, Amy L. Rector, Erin N. DiMaggio, Christopher J. Campisano, David A. Feary, Baro’o Mohammed Ali, Daniel Chupik, Alan L. Deino, Dominique I. Garello, Mohammed Ahmeddin Hayidara, Ellis M. Locke, Omar Abdulla Omar, Joshua R. Robinson, Eric Scott, Irene E. Smail, Kebede Geleta Terefe, Lars Werdelin, William H. Kimbel, J. Ramón Arrowsmith and Kaye E. Reed, 13 August 2025, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09390-4

Funding: U.S. National Science Foundation

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.