A newly discovered Denisovan gene, hidden within human DNA, may have helped the first Americans adapt to their new world.

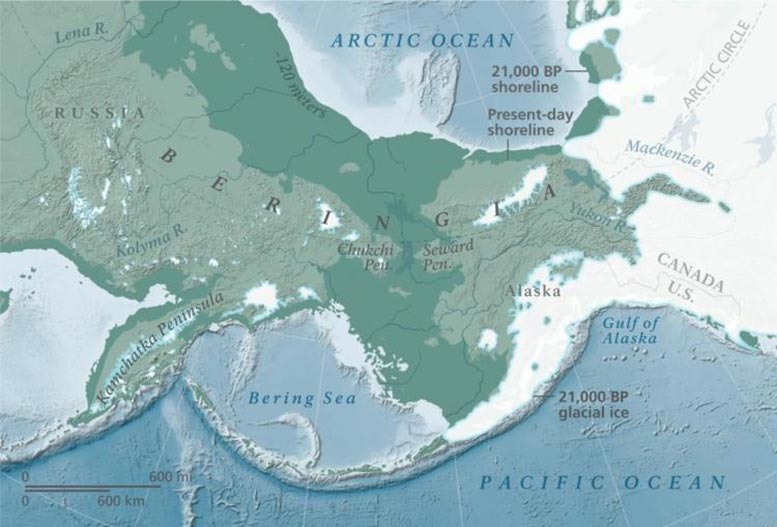

Thousands of years ago, early humans braved a dangerous migration, traveling across vast stretches of ice over the Bering Strait to reach the unfamiliar lands of the Americas.

According to new research from the University of Colorado Boulder, these travelers may have brought along something unexpected: a piece of DNA inherited from a now-extinct hominin species. This genetic legacy could have played a key role in helping them survive and adapt to the challenges of their new environment.

The researchers recently published their findings the journal Science.

“In terms of evolution, this is an incredible leap,” said Fernando Villanea, one of two lead authors of the study and an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at CU Boulder. “It shows an amount of adaptation and resilience within a population that is simply amazing.”

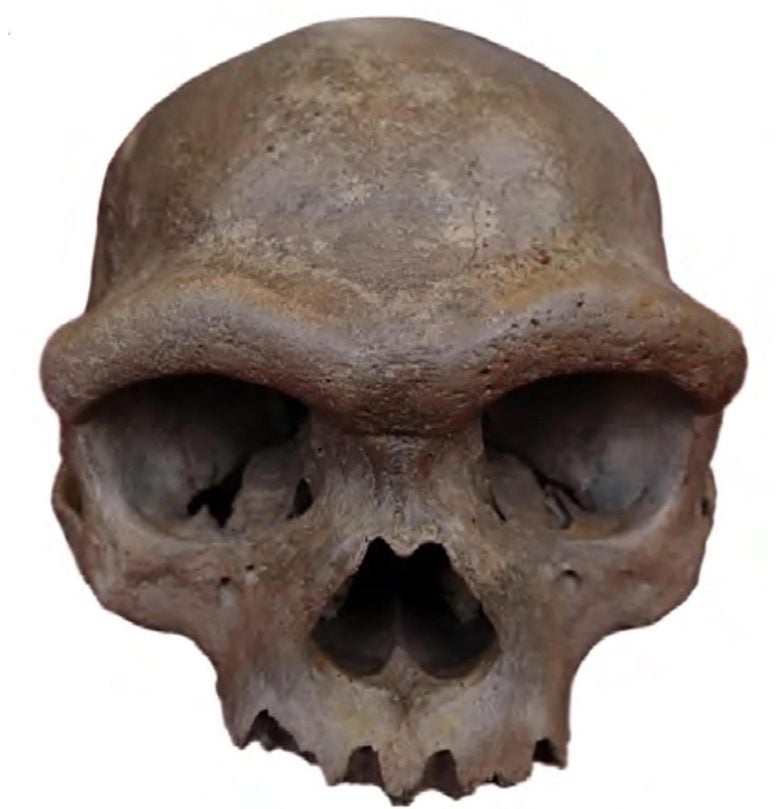

The work focuses on Denisovans, a mysterious branch of the human family tree. These ancient relatives once lived across a wide region stretching from modern-day Russia down to Oceania and westward to the Tibetan Plateau, before disappearing tens of thousands of years ago. Much about them is still uncertain: the first Denisovan was only identified 15 years ago through DNA extracted from a bone fragment discovered in a Siberian cave. Physical traits remain largely speculative, though like Neanderthals, they may have had heavy brows and lacked chins.

“We know more about their genomes and how their body chemistry behaves than we do about what they looked like,” Villanea said.

A growing body of research has shown that Denisovans interbred with both Neanderthals and humans, profoundly shaping the biology of people living today.

To explore those connections, Villanea and his colleagues including co-lead author David Peede from Brown University, examined the genomes of humans from across the globe. In particular, the team set its sights on a gene called MUC19, which plays an important role in the immune system.

The group discovered that humans with Indigenous American ancestry are more likely than other populations to carry a variant of this gene that came from Denisovans. In other words, this ancient genetic heritage may have helped humans survive in the completely new ecosystems of North and South America.

A little-known gene

Villanea added that MUC19’s function in the human body is about as mysterious as Denisovans themselves. It’s one of 22 genes in mammals that produce mucins. These proteins make mucus, which, among other functions, can protect tissues from pathogens.

“It seems like MUC19 has a lot of functional consequences for health, but we’re only starting to understand these genes,” he said.

Previous research has shown that Denisovans carried their own variant of the MUC19 gene, with a unique series of mutations, which they passed onto some humans. That kind of admixture was common in the ancient world: Most humans alive today carry some Neanderthal DNA, whereas Denisovan DNA makes up as much as 5% of the genomes of people from Papua New Guinea.

In the current study, Villanea and colleagues wanted to learn more about how these genetic time capsules shape our evolution.

The group pored through already published data on the genomes of modern humans from Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Colombia, where Indigenous American ancestry and DNA are common.

They discovered that one in three modern people of Mexican ancestry carry a copy of the Denisovan variant of MUC19—and particularly in portions of their genome that come from Indigenous American heritage. That’s in contrast to people of Central European ancestry, only 1% of whom carry this variant.

The researchers discovered something even more surprising: In humans, the Denisovan gene variant seems to be surrounded by DNA from Neanderthals.

“This DNA is like an Oreo, with a Denisovan center and Neanderthal cookies,” Villanea said.

A new world

Here’s what Villanea and his colleagues suspect happened: Before humans crossed the Bering Strait, Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals, passing the Denisovan MUC19 to their offspring. Then, in a game of genetic telephone, Neanderthals bred with humans, sharing some Denisovan DNA. It’s the first time scientists have identified of DNA jumping from Denisovans to Neanderthals and then humans.

Later, humans migrated to the Americas, where natural selection favored the spread of this borrowed MUC19.

Why the Denisovan variant became so common in North and South America but not in other parts of the world isn’t yet clear. Villanea noted that the first people who lived in the Americas likely encountered conditions unlike anything else in human history, including new kinds of food and diseases. Denisovan DNA may have given them additional tools to contend with challenges like these.

“All of a sudden, people had to find new ways to hunt, new ways to farm, and they developed really cool technology in response to those challenges,” he said. “But, over 20,000 years, their bodies were also adapting at a biological level.”

To build that picture, the anthropologist is planning to study how different MUC19 gene variants affect the health of humans living today. For now, Villanea said the study is a testament to the power of human evolution.

“What Indigenous American populations did was really incredible,” Villanea said. “They went from a common ancestor living around the Bering Strait to adapting biologically and culturally to this new continent that has every single type of biome in the world.”

Reference: “The MUC19 gene: An evolutionary history of recurrent introgression and natural selection” by Fernando A. Villanea, David Peede, Eli J. Kaufman, Valeria Añorve-Garibay, Elizabeth T. Chevy, Viridiana Villa-Islas, Kelsey E. Witt, Roberta Zeloni, Davide Marnetto, Priya Moorjani, Flora Jay, Paul N. Valdmanis, María C. Ávila-Arcos and Emilia Huerta-Sánchez, 21 August 2025, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adl0882

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.