The 19th-century novelist Honoré de Balzac was Catholic, French to the core and obsessed with the material details of French society. Yet there is something profoundly Hindu in the way he sought to understand the world.

Balzac was born in the final year of the 18th century. As he began his career, European literature was turning away from the abstraction of the previous century’s Enlightenment and towards realism. Realist writers, including the French novelist Stendhal, insisted that to understand the human condition, they first had to know local customs, political and economic pressures – and the inner lives of individuals.

Balzac was the supreme example of this shift. His vast work La Comédie Humaine (1829-48) was made up of nearly 100 interconnected novels and stories. It sought to map French society, not by generalising from above, but by diving into the specific lives of his characters.

In the preface to the work, Balzac declared: “French society would be the real author; I should only be the secretary.” He described society as a zoological landscape populated by distinct species and insisted that truth emerged from a complete inventory of these types: “the dress, the manners, the speech, the dwelling of a prince, a banker, an artist, a citizen, a priest, and a pauper are absolutely unlike, and change with every phase of civilisation.”

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

In his novel Le Père Goriot (1835), Balzac devoted the entire opening chapter to the description of a grim boarding house. The copious descriptions of the layout, decoration and even smells serve as a physical embodiment of the moral, social, economic and physiological condition of the dwellers.

In the serial novel Illusions Perdues (1837–1843), meanwhile, he dissected the Parisian press, provincial printing shops and the cruel economy of literary fame. Even the cut of a waistcoat, the price of paper, or the decor of a salon became data for understanding society.

Though his work is known for character typology (grouping them by traits), no two characters of the same “type” are alike. This showed his commitment to individuality within universal archetypes.

Other novelists including Gustave Flaubert, Émile Zola, Charles Dickens and Leo Tolstoy, all treated the individual as the key to the social whole. But Balzac articulated the method most systematically: he aimed to know everything about a society by knowing each part in all its messy detail.

Balzac’s mandala

This method resembles a central idea in Hindu philosophy. The formula tat tvam asi (that thou art), from the Sanskrit Hindu text Chandogya Upanishad (8th to 6th century BC), says that the individual self (ātman) is identical to the universal essence (brāhman). It’s the idea that understanding the universe comes from realising that the universe is within the self.

The Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita offers a similar vision, where the deity Krishna declares: “I am the Self, O Gudakesha, seated in the hearts of all creatures. I am the beginning, the middle, and the end of all beings.”

Balzac was no expert on Hinduism. But he does have a character (Louis Lambert) write about it in La Comédie Humaine:

Sivaism, Vishnuism, and Brahmanism, the three primitive creeds, originating as they did in Tibet, in the valley of the Indus, and on the vast plains of the Ganges, ended their warfare some thousand years before the birth of Christ by adopting the Hindoo Trimourti. The Trimourti is our Trinity.

The passage wrongly asserts that Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Brahmanism emerged as separate “creeds”, when in fact they are interrelated and complementary currents within Hindu thought. The claim that they resolved their differences by adopting the Trimurti, and that this was the origin of the Christian Trinity, reflects a common orientalist tendency. It misunderstands Hindu ideas and co-opts them into a Christian framework.

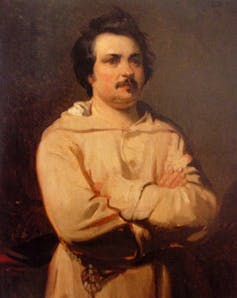

Museum of Fine Arts of Tours

But this misreading makes the structural parallel all the more interesting. Balzac didn’t import Hindu ideas; the resemblance emerges from his method. La Comédie Humaine is structured like a mandala: a layered map of a universe made from precise local detail.

In Hindu traditions, a mandala is not merely a symbol but a sacred diagram of the cosmos. Later Hindu and Buddhist cosmology develops it into a meditative tool – an intricate geometric pattern centred on the self and the divine. A mandala places a sacred centre at the heart of an ordered arrangement, expressing the idea that the universal is embedded in the particular. Each part reflects the whole, and the path to the centre is through a journey inward, detail by detail.

Balzac’s work functions similarly. La Comédie Humaine’s order arises not from a single philosophical system, but from mapping the interlocking elements of social existence. Like a mandala, it invites readers to move inward; from the material facts of a boarding house or a printing press to the inner motives of his characters.

Balzac explains his method of structuring La Comédie Humaine in the preface:

It was no small task to depict the two or three thousand conspicuous types of a period… This multitude of lives needed a setting – a gallery. Hence the very natural division … into the Scenes of Private, Provincial, Parisian, Political, Military, and Country Life. … Each has its own sense and meaning, and answers to an epoch in the life of man.

In this sense, Balzac’s realism is not merely descriptive but architectural: a literary mandala of modern society. The affinity with the Hindu mandala suggests that La Comédie Humaine, which has more than 2,000 characters, enacts a recognisably Hindu way of knowing: to know the world, one must first know its inward forms.

Balzac’s Catholic worldview, his (often) moralising narrator, his encyclopaedic ambition, all root him in 19th-century France. But the kinship with Hindu inwardness points to something deeper. His great realist novel, for all its materialism, remains part of a broader human project – to understand the universe by beginning with the self.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Harsh Trivedi’s suggestion:

For readers seeking complex but entertaining social narratives outside the western canon, Sacred Games by Vikram Chandra (2006) offers an Indian counterpart to Balzac’s realism.

ZUMA Press, Inc.

Set in contemporary Mumbai, the novel intricately weaves crime, politics and mythology. The ripples of the many characters’ actions interlock like a mandala, forming a complex, layered fiction. The protagonist, Sartaj Singh, first appeared in Chandra’s earlier short story collection Love and Longing in Bombay (1997), showcasing his use of recurring characters and interconnected narratives reminiscent of Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.