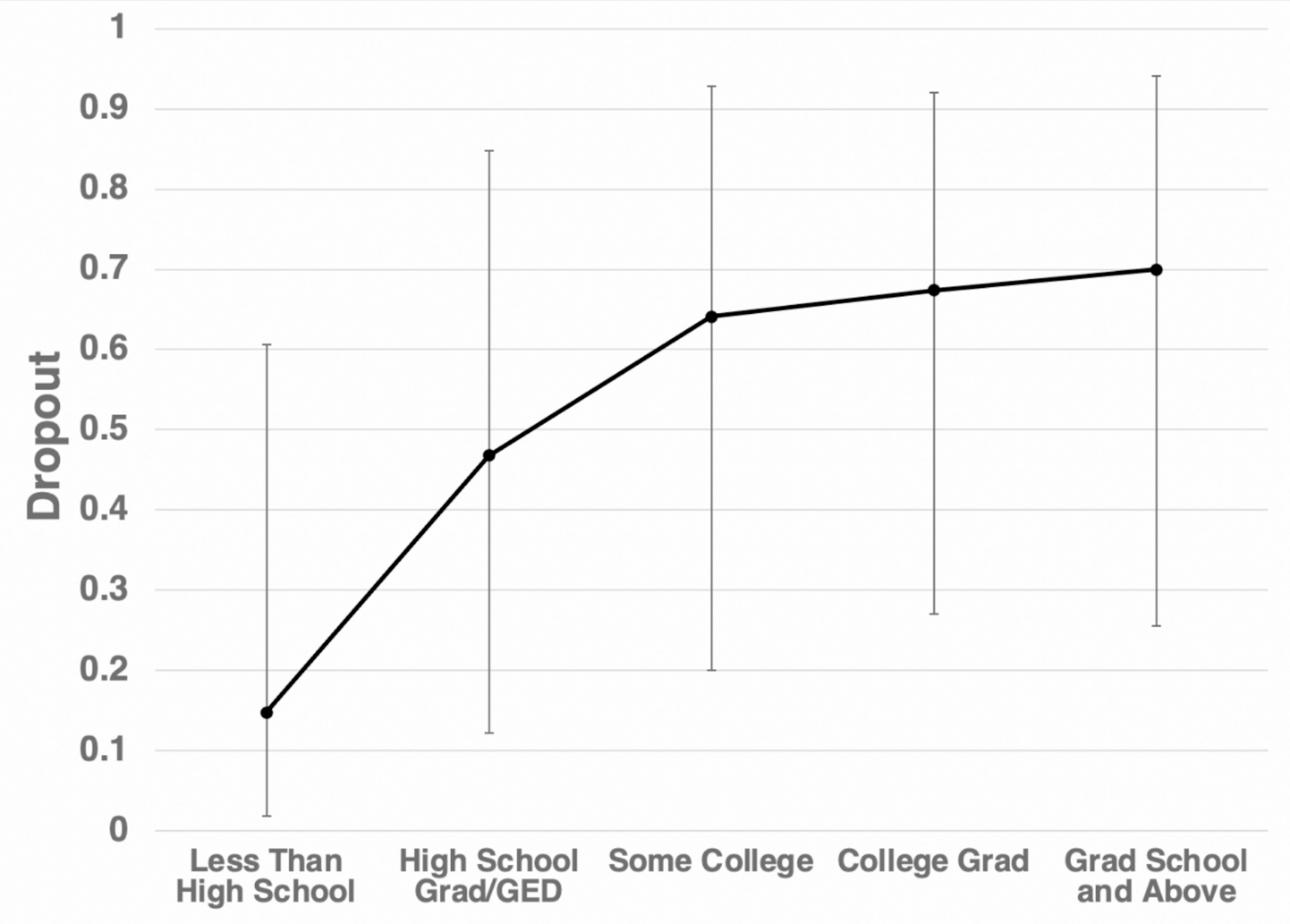

The goal of this study was to identify variables associated with discontinuation from pharmacological trials for adults with trichotillomania. It was expected that demographic and clinical variables may be predictive of attrition and our results partially supported these hypotheses. Regarding demographic variables, only education level was found to be a significant predictor of dropout. This trend appears to be driven by the low number of dropouts from lower education attainment. It is possible that attaining a higher level of education equips patients with greater knowledge or greater financial or schedule flexibility to search for alternatives if a patient decides they no longer wish to continue with a trial. This finding is consistent with the previous literature [24] in which education level was associated with discontinuation in a behavioral trial for depression. Unlike various other disorder studies [10–11], age of those who discontinued did not differ significantly from those who completed the trials. However, consistent with prior with literature [10], gender did not significantly predict dropout. Due to protocol differences, race/ethnicity was not collected for a majority of the studies and thus had to be excluded from our model. It is also worth noting that the majority of participants in these studies were female and Caucasian. This relative lack of diversity further limits our ability to discern the use of gender and race/ethnicity as predictors for discontinuation.

With regrads to co-morbidities, patients with a history of depression were more likely to dropout. Depression has not been previously implicated as a predictor of dropout in prior literature. However, within the context of a randomized control trial this finding could have a few explanations. Patients with a history of depression may begin to feel hopelessness about their treatment earlier in the trial resulting in dropout. Alternatively, increased fatigue or lower motivation would make paitents with depression more likely to be lost to follow up. In contrast to prior literature that previously implicated both lower [25] and higher [26] baseline symptom severity in attrition, symptom severity of trichotillomania patients was not found to be a significant predictor of dropout. Similarly, presence of adverse events also did not significantly predict dropout. Taken together, this seems to indicate that attrition is not necessarily dependent upon the response to treatment by itself nor by the negative effects that some patients experienced during the trial.

These findings must also be interpreted within the context of the current state of trichotillomania treatment. Currently there are no FDA-approved pharmacological treatments specifically for trichotillomania. Moreover, it is arguably more difficult to find a health professional for treatment of trichotillomania than for more common disorders such as depression or anxiety. Due to these more limited options, participants who join trichotillomania trials may be more inclined to stay the course of the trial. If true, this may provide a possible explanation as to why factors that had previously been implicated in attrition of pharmacological trials of other psychiatric disorders such as age or symptom severity did not follow the same trend with trichotillomania patients.

There are limitations to the current study, particularly sample size and demographics. While the current study chose to aggregate trials from a singular site, it would be beneficial to aggregate more trials such as Doughtery et al. (2006) [27] or van American et al. (2010) [28], especially to enroll a more diverse and representative patient population. As such, generalizability of the current study may be limited. Furthermore, by treating dropout as a binary, our ability to capture the nuances of timing and reasoning for dropout. While we attempted to address this problem by analyzing dropouts before and after the halfway point of their respective study, it is still a relatively narrow view of attrition.

Regrading the model, the creation of the generalized linear mixed model required the exclusion of many of our collected variables due to missing values and collinearity. This limited our ability to properly address all our potential predictors at once, notably race/ethnicity, employment and other measures of symptom severity. Ideally, thorough collection of these demographic and clinical factors in their entirety would allow for proper assessment of their importance in attrition. Additionally, it must be noted that the confidence intervals of both education and history of depression are somewhat large, possibly due to limited sample size or the nature of our binary dependent variable. Finally, future studies should also consider pursuing other demographic variables such as socioeconomic status as well as other cognitive measures such as the Barrett Impulsive Scale or Start Stop Task. Impulsivity, a related cognitive measure to inhibition response, is common hallmark of trichotillomania and thus may also play a role in patient discontinuation.

Still, the problem of trial discontinuation remains prominent in trichotillomania studies. Overall, there was a 23% dropout rate among participants with an almost equal number of particpants dropping out before (52%) and after (48%) the midway point. This indiscriminate dropout temporally suggests that length of trial is not a significant factor when it comes to dropout. Taken together with the fact that group assignment and presence of adverse events also were not implicated in rates of discontinuation, most participants appear willing to tolerate the current double-blinded methodology of clinical trials. The main reason cited for participants “dropping out” from our aggregated trials was not due to the design of the trials themselves, but rather due to loss to follow up or not showing up to check-ins. While it may not be possible to intervene in a patients’ prior education attainment or history of depression, it is vital that researchers recognize and combat these factors with intentional efforts to provide additional support. Interventions may include clear communication and expectation setting reinforced throughout the trial, more flexible scheduling and increased check-ins offered over telephone or telehalth in order to more actively evaluate patient feelings of potential attrition and intervene before becoming lost to follow up.