R.F. Kuang In Conversation with Dean Nelson

6:30 p.m. Thursday, September 11

Brown Chapel, Point Loma Nazarene University

Lomaland Dr, San Diego, CA 92106

$43 + tax and fee (includes a copy of the book)

MORE INFO

Rebecca F. Kuang was in the middle of pursuing her doctorate at Yale when she heard people around her joking that “academia is hell.”

“ So being me, I took that very literally and I thought, ‘What if academia literally was hell?’” Kuang said. “‘How silly would that be?’”

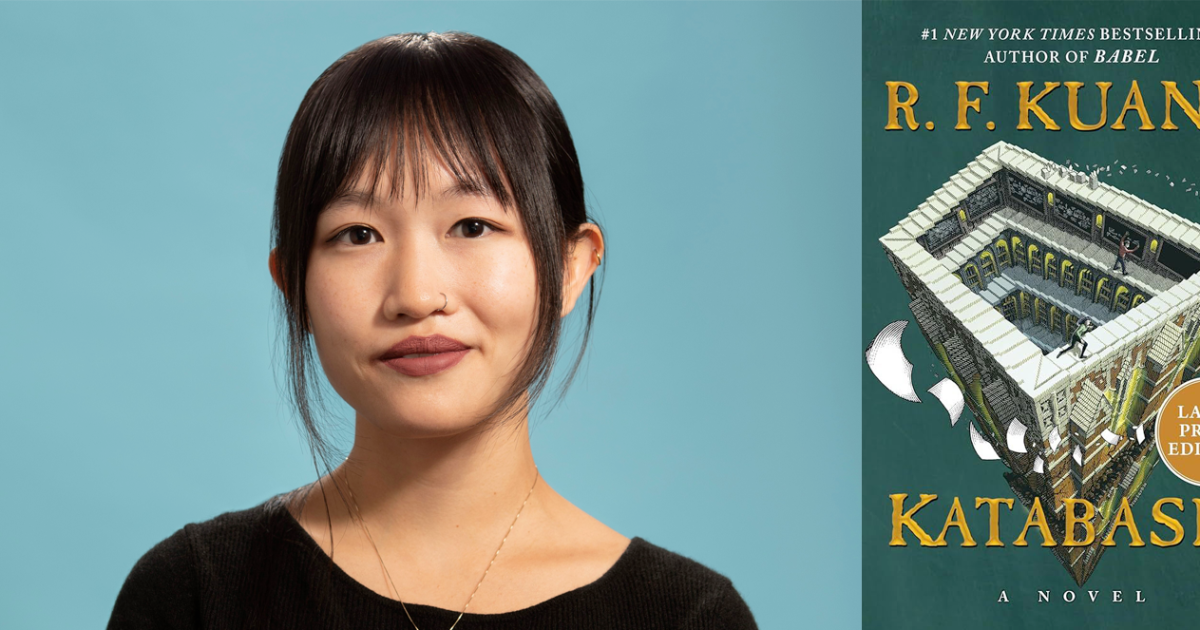

“Katabasis” is Kuang’s sixth novel. The book follows two graduate students, Alice Law and Peter Murdoch, on a journey into hell to save their professor’s soul after he is accidentally killed during a magical experiment.

But what started out as a satire of academia, evolved into something darker, as Kuang began exploring themes of mental health, suicide and chronic illness.

Kuang joined Midday Edition to talk about her inspirations for “Katabasis” and the absurdities of academia.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

On academia as hell

The reason why hell is a university in this novel is that I have a theory that hell presents itself differently to everybody who encounters it. And we see a lot of this in ancient depictions and myths of hell. There’s a lot of Chinese paintings, for instance, where hell is just a regular courtroom.

And of course, the Egyptian pharaohs were expecting to die and wake up surrounded by their favorite pets and their favorite servants and all the things they liked. So I was really curious that people thought that the afterlife was just a mirror image — a continuation of their life. They knew one possible explanation for this is that the punishments in hell would only make sense within a moral universe that was legible to you — a world that you were already familiar with, but were looking at from a different angle.

I think geographically it is very on the nose inspired by Dante’s “Inferno” — the descriptions of desert landscapes, the barren rocks and the suffocating bogs of wrath.

R.F. Kuang

So that’s why Peter and Alice are in hell as a campus, but actually hell is the state of flux that constantly reconstitutes itself and presents itself differently the further they trek throughout.

I think the point I’m trying to get across is not that academia is uniquely hellish, but for these two people who have spent their whole lives mired in academia, the punishments of hell would only make sense in a campus format.

On being inspired by Dante and Eliot

I think geographically it is very on the nose inspired by Dante’s “Inferno” — the descriptions of desert landscapes, the barren rocks and the suffocating bogs of wrath. All of that is imagery that I was so taken with when I read it in “Inferno” that I put my own riff on them in “Katabasis.”

But it’s actually T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” that is the most influential text on how hell is described. There is this line in “The Waste Land” that reads, “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” And when I read that, I got full-body shivers. I thought, “This is amazing.” That line forms the backbone of the alienating, disquieting creep of fear that Alice and Peter feel as they trek further into the deeper courts and start realizing that perhaps they’re not alone and something is stalking them throughout this desert landscape.

On Alice Law’s delusions

Alice’s issue is that she’s totally delusional, and I think this is a common personality type in academia. People who constantly believe against the impossible, who are so passionate and obsessive about their research, that they’re willing to overlook a lot of things. For instance, the joke that every PhD student implicitly understands is the existence of a job market. Most of us doing PhD knows that we probably won’t get jobs — there just aren’t enough positions to go around. The PhD is in this impossible endeavor, but Alice thinks that if you just close your eyes and pretend that there’s nothing wrong — that everything’s going to be OK — then these systems of belief are going to keep you going up until the very end.

On a very personal level, the book was a way for me to explore this basic question of why life is worth living and how you get there.

R.F. Kuang

So the key to Alice’s character is understanding that she’s wrapped herself in all these catechisms, these cages of belief that will ultimately fail her and fall apart. And when that happens, she will have nothing to orient herself. So much of the book is exploring how she finally comes to terms with the truth and learns to break free of the delusions that she has relied on for her survival.

On rivalries as romance

I like to write rival dynamics. They’re always so much fun for me because a rivalry is a kind of romance, and there’s so many examples in great works of literature where the rivalry feels more intimate and more sensual, almost, than a romantic relationship.

As academic rivals, Alice and Peter have been forced to pay very close attention to one another. They’re probably the most careful readers of the other’s work. I mean, Alice can recognize every single letter of Peter’s handwriting. They understand how the other thinks. They understand the patterns of their minds, the mistakes that they tend to make or their particular forms of brilliance. That means that when they’re opposed to each other, they can go to nearly deadly warfare.

But when they’re working on the same team, they’re basically unstoppable. That was a really fun dynamic to write.

On crafting her sixth novel

I find that every book feels harder to write because I’m learning more about craft and I am more attentive to issues that I never even would’ve noticed before. So I think certainly with this book, I was very careful with every sentence, every word choice. I wasn’t like that earlier in my career.

When I was writing “The Poppy War” trilogy, the words just sort of flowed out of me because I wasn’t interested in the art of the sentence. I was just interested in getting my ideas across. Now I’m learning more about poetry and I’m thinking more about the rhythm and the musicality of a sentence. I did a lot more reading out loud of this book than I have with previous books.

I think my ear is just becoming sharper and sharper for the sound and shape of language as I get better at writing, and I hope that’s reflected in the prose.

On social media reading guides

Oh, I think it’s amazing. I’ve been shown some of these videos and they make me really, really happy. I think in an era of all these attacks against intellectualism and a general dumbing down of culture, the fact that young people are on TikTok telling each other to read the “Aeneid” is so, so cool. I’m happy to have contributed to that in any little way.

Personally, I don’t think that there’s a list that you have to read before you read the book. I’ve tried to make everything very accessible and intelligible, even if you have no background in any of the fields that I’m writing about, because I also don’t have an academic background in philosophy or logic or math. I’ve had to explain these concepts in terms that were accessible to myself.

What I hope most of all is that readers who pick up on references in “Katabasis” then go on and read those texts as well. So if you read the book and then decide you wanna read T.S. Eliot or Jorge Luis Borges or Nabokov or Dante, then all power to you — and I hope you have a really good time.

On life’s bigger questions

I think on a very personal level, the book was a way for me to explore this basic question of why life is worth living and how you get there. So I hope that anybody who is in a similar place will find some comfort in the book and also think that the question of life has gotten more interesting.