Back when I worked at Goldman, I remember one particular Fed meeting when the central bank had hiked but – to my complete consternation – the Dollar fell. I asked the head of currency trading at the time how this could have possibly happened. He looked me straight in the eye and said: “there were more sellers than buyers.”

That’s pretty much what’s going on with the Yen right now. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is hiking, but the Yen is down to its lowest level in over 20 years, tumbling below the low it made mid-2024 when Japanese interest rates were much lower. It might sound trite to attribute this to there being “more sellers than buyers,” but there’s a lot more wisdom in this comment than you might think. This post explains what’s going on.

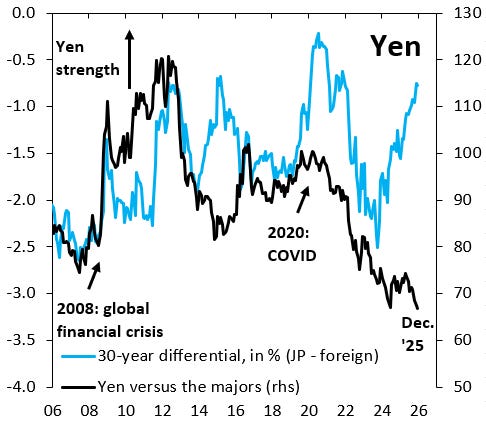

The black line in the chart above shows the trade-weighted Yen against the majors, where I use the same weights as the BoJ to average up bilateral currency pairs. The blue line shows the analogous interest rate differential based on 30-year government bond yields. As I’ve noted in many previous posts, longer-term Japanese yields have risen very sharply this year, which has moved the 30-year differential sharply in favor of the Yen. That should make it more attractive for global capital markets to invest in Japan and should therefore cause the Yen to appreciate. That isn’t happening, which might seem like a puzzle but it really isn’t.

The vertical axis in the chart above shows the 30-year government bond yields that go into the rate differential in the first chart. The horizontal axis plots gross government debt in percent of GDP. While it’s true that the interest differential has moved a lot in favor of the Yen, it’s also true that – given Japan’s monstrous level of government debt – longer-term yields are still much too low relative to where they would be if the BoJ weren’t still a massive buyer of government debt. This bond buying is keeping yields artificially low, which should really be much higher due to risk premia. Because these risk premia aren’t allowed to show up in the bond market, they show up in the Yen instead, which is the reason it keeps falling.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Japan’s longer-term yields have been rising, but – on a risk-adjusted basis – that rise isn’t nearly enough to stabilize the Yen. Another way to say this: markets think risk of a debt crisis is rising sharply. Yen depreciation won’t stop until yields are allowed to rise far more, forcing the government to pursue fiscal consolidation and bring down debt. Japan needs to stop being in denial.