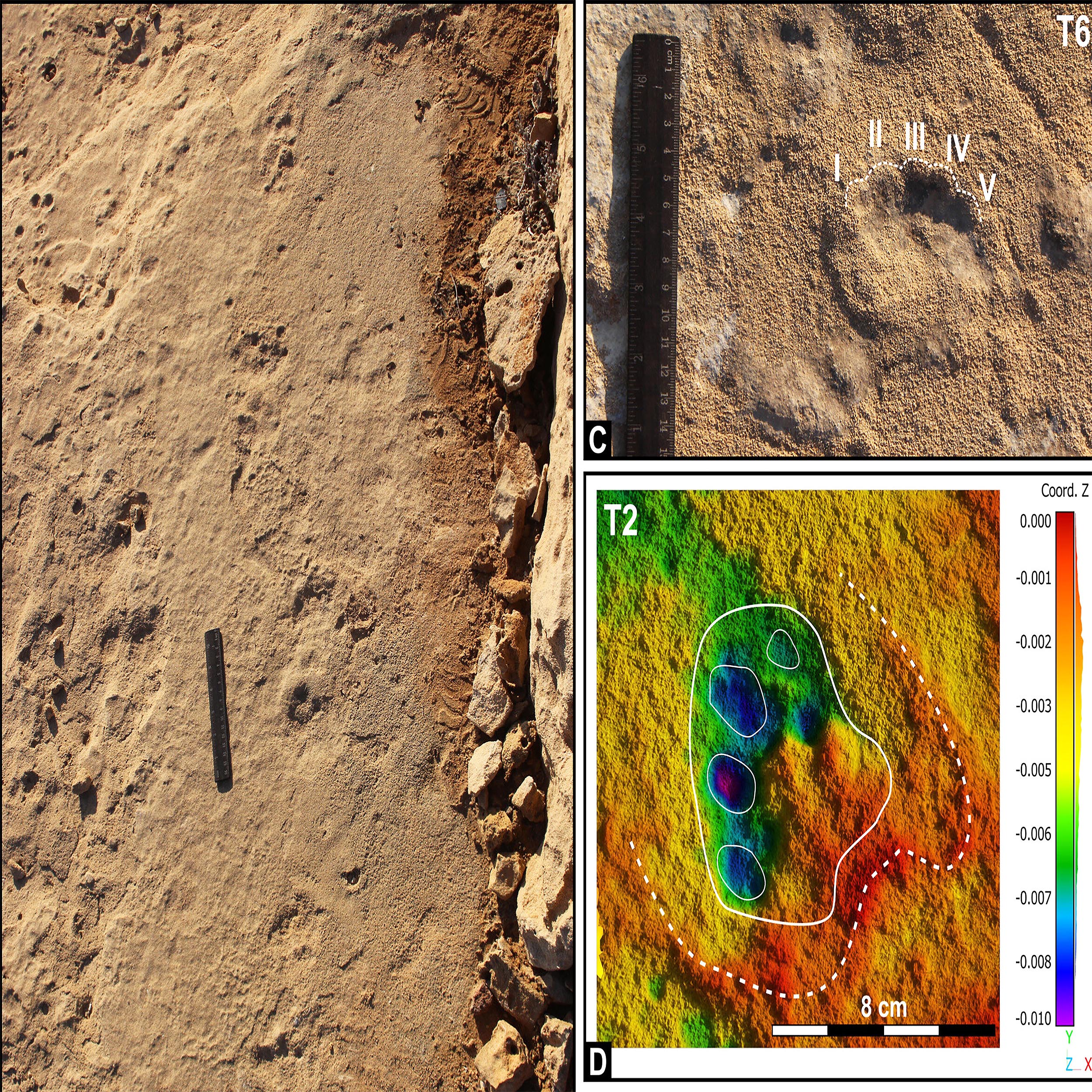

The Murcia tracksites confirm that straight-tusked elephants, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, crossed Spain’s southeastern coastal corridor about 125,000 years ago, leaving behind footprints that are now locked in ancient sand dunes.

Researchers from…

The Murcia tracksites confirm that straight-tusked elephants, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, crossed Spain’s southeastern coastal corridor about 125,000 years ago, leaving behind footprints that are now locked in ancient sand dunes.

Researchers from…