Some planets may be soot-rich rather than water-based. Atmosphere studies will be key to understanding their true nature.

Astronomers generally consider water worlds to be among the most common types of planets in our galaxy, largely because of their low densities and the abundance of water ice beyond a star’s “snow line.” However, a new study led by Jie Li and colleagues at the University of Michigan proposes an alternative explanation: some of these planets may not be dominated by water at all, but instead by a very different material known as soot.

In astronomy, a soot planet is not literally a planet made of black powder. Here, “soot” refers to refractory organic carbon, a compound containing carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen that scientists often abbreviate as CHON. This type of carbon-rich material is widespread in the solar system, with estimates suggesting it accounts for as much as 40 percent of the total mass of comets.

From comets to soot lines in planet formation

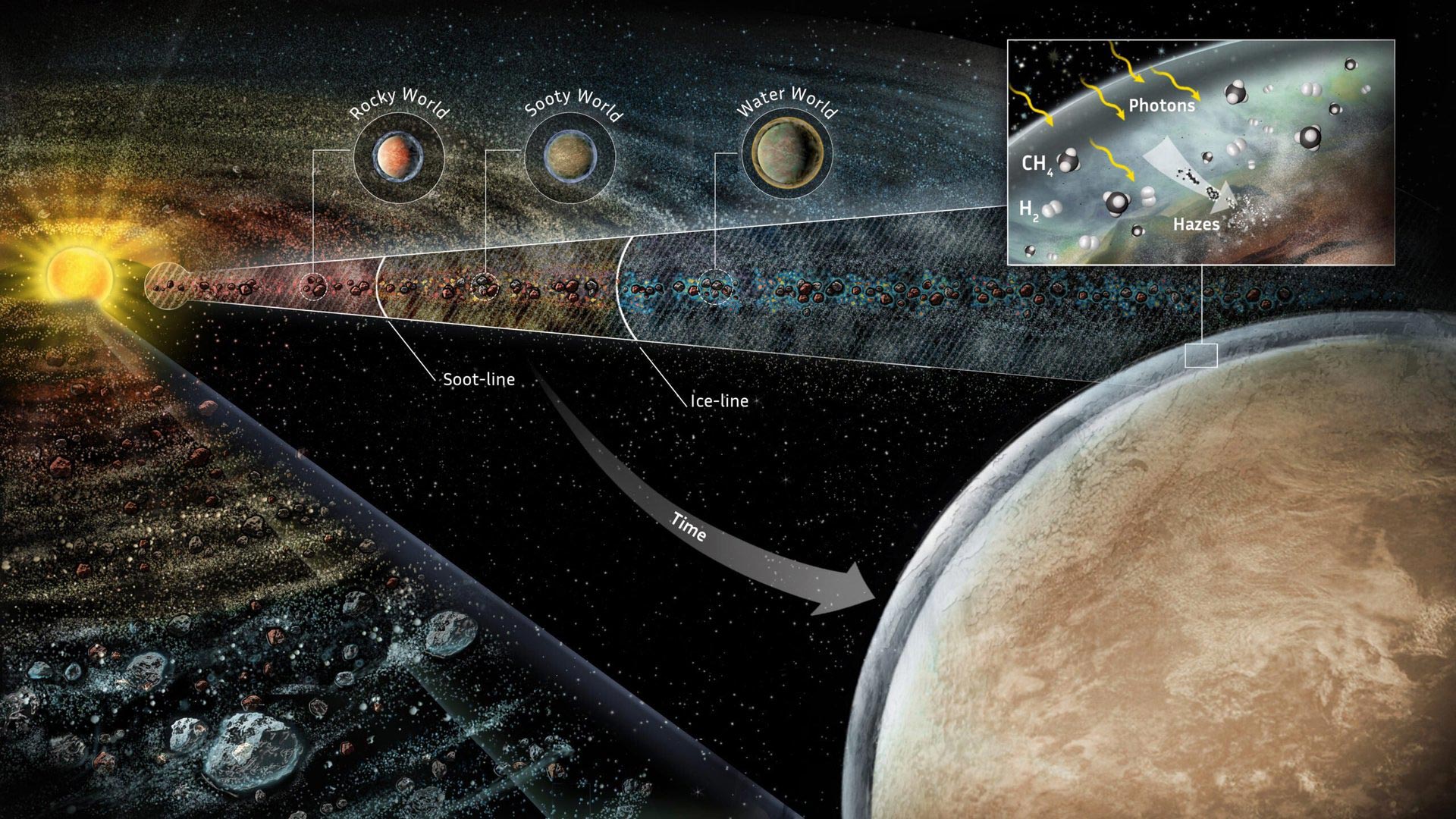

Because comets are often considered snapshots of the solar system’s early history, particularly during its protoplanetary phase, their composition suggests that soot was plentiful during the time planets were forming. The researchers propose that, just as there is a “snow line” marking the distance from a star where water ice can remain stable, there may also be a “soot line.” This boundary, located closer to the star than the snow line, would define the region where soot could persist and contribute significantly to the makeup of developing planets.

Fraser discusses Water Worlds and how life might form on them.

In fact, according to the paper, there would be three distinct zones of protoplanetary discs, each giving birth to a unique type of planet. The inner zone would only result in rocky works, like Earth and Mars, and it would be too hot for the soot to stay together, making “soot” in this area very unlikely. Past the “soot line” but before the “snow line”, planets could form that were mainly composed of soot, but with very little water, as it would still be too hot for water ice to exist in this area.

These planets would look a lot like Titan, with methane atmospheres or something equivalent, and could be made up of as much as 25% soot by mass. Farther out past the “snow line”, most planets would be a combination “soot-water world”, where soot would still play a large role in the composition of the planet, but water would as well. In fact, the paper models two different types of soot-water worlds, a “dry” version that was only 25% water, and a “wet” one that contains 50% water, both of which would still contain 15-20% soot in their compositions.

The problem of distinguishing planet types

Those models show a particularly interesting feature – based on the mass-radius relationships, it is impossible to tell apart soot worlds and more traditional water worlds. In other words, many of the “mini-Neptunes” in the exoplanet catalog that were originally thought to be water worlds could actually be composed of carbon-rich materials rather than water. It would take looking at their actual atmospheres to determine which category they belonged to.

Fraser discusses the discovery of methane, thought to be one of the main components of Soot Worlds, on exoplanet WASP-80b.

The James Webb Space Telescope has already started doing so for some exoplanets. It’s detected methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of K2-12b and TOI-280d, two “sub-Neptunes” that, while they are currently located within the soot line for their respective stars, might have formed outside of it and migrated inward over their lifetimes.

In particular, TOI-280d has a notably high carbon to oxygen ratio, indicating that it might be a soot planet as described in the paper. These types of planets have interesting implications for habitability. They could have diamond cores, which would slow the cycling of volatiles in the planet’s mantle and have a much harder time providing a magnetic field to protect any primitive life from cosmic rays. However, they would also be flush with methane and other volatile organics, which are thought to be prerequisites for prebiotic chemistry.

Ultimately, understanding the fate of many of these planets will require – you guessed it – more data. Atmospheric checks, as well as more detailed models of ways to differentiate between water worlds and soot world,s need to be explored and delineated. While astronomers get to work on doing that, maybe an enterprising film director can pitch a movie about a character sailing an exoplanet’s methane seas in an insulated boat. Kevin Costner’s still actively acting after all.

Reference: “Soot Planets instead of Water Worlds” by Jie Li, Edwin A. Bergin, Marc M. Hirschmann, Geoffrey A. Blake, Fred J. Ciesla and Eliza M.-R. Kempton, 22 August 2025, arXiv.

DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2508.16781

Adapted from an article originally published on Universe Today.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.