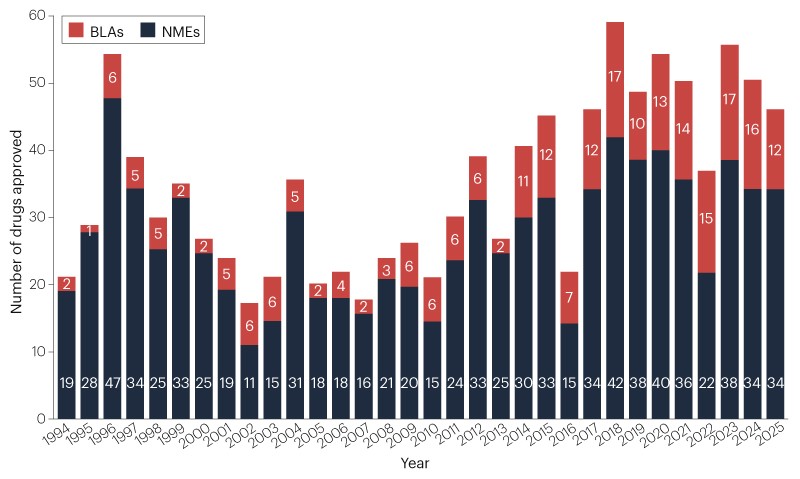

Drug developers secured approvals for 46 new therapeutic agents from the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) in 2025. This cohort brings the 5-year average down a touch, to 48 new drugs per year (Fig. 1, Table 1). Approvals are still well above the historic average, of 36 new drugs per year since 1993.

Fig. 1 | Novel FDA approvals since 1993. Annual numbers of new molecular entities (NMEs) and biologics license applications (BLAs) approved by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). See Table 1 for new approvals in 2025. Products approved by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), including vaccines and gene therapies, are not included in this drug count (Table 2). Source: FDA.

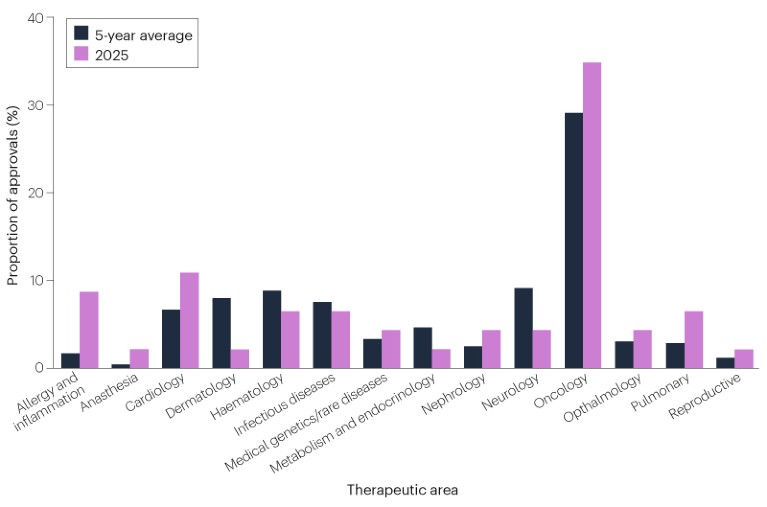

Cancer remains the most common therapeutic area for newly approved drugs (Fig. 2). 16 (35%) of CDER’s newly approved drugs were for cancer, up from a rolling 5-year average of 29%. The other most active areas were cardiology, with 5 (11%) new approvals, and allergy and inflammatory diseases, with 4 (9%) new approvals.

Fig. 2 | CDER approvals by therapeutic areas. Indications that span multiple disease areas are classified under only one, based on which FDA office and division reviewed the approval application. Source: Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, FDA.

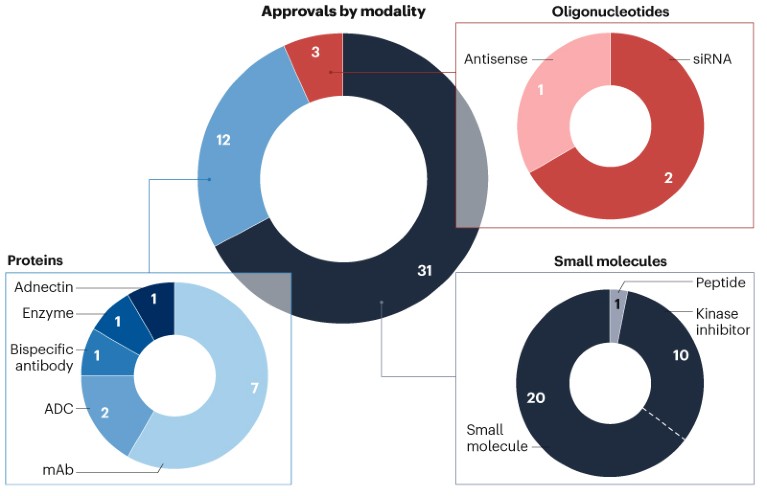

Drug developers continue to advance a diverse array of modalities, including a first adnectin-based biologic therapy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 | CDER approvals by modality. Small molecules, including peptides of up to 40 amino acids in length, and oligonucleotides are approved as new molecular entities (NMEs). Protein-based candidates are approved through biologics license applications (BLAs). ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; mAb, monoclonal antibody; siRNA, small interfering RNA. Source: Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.

It was also the biggest year yet for kinase inhibitors, which accounted for around one third of the newly approved small molecules. Novartis’s remibrutinib (Rhapsido) became the 100th kinase inhibitor to secure FDA approval, showcasing the continued expansion of this type of drug beyond oncology. “The area is not played out yet,” University of Dundee’s Philip Cohen told Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.

The FDA has not yet released its breakdown of these new approvals by their regulatory designations.

CBER approved 8 notable new products (Table 2), including a first gene therapy from a non-profit organization.

The average peak sales for the novel CDER and CBER approvals is around US$1.2 billion, shows an upcoming analysis by Boston Consulting Group. The median is around $600 million.

2025 was, however, a tumultuous year for the FDA, with dramatic staffing and policy changes since President Donald Trump appointed Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to lead the US Department of Health and Human Services. In the first 9 months of the year, more than 18% of the FDA’s CDER and CBER employees were fired or quit. CDER had five directors over the course of the year.

The agency nevertheless introduced new approval programmes and pathways. It launched its FDA Commissioner’s National Priority Voucher (CNPV) pilot programme, which aims to cut review timelines from the usual 10–12 months down to 2 months. The controversial programme risks politicizing the drug review process and eroding regulatory standards, some FDA staffers and watchdogs have warned. The FDA also proposed a plausible mechanism pathway for situations where randomized trials are not feasible, including for bespoke n-of-1 therapies. And it announced plans to phase out animal toxicity testing.

More changes could be coming. The FDA typically requires drug developers to run two pivotal trials to secure full approvals for their products, but the agency is reportedly moving towards making the default requirement a single trial.

The cancer crowd

Cancer continues to dominate industry’s pipeline. But while oncology drugs contribute the bulk of the new approvals, they account for just two multi-blockbuster drugs, with earning potential of over $2 billion annually according to Evaluate forecasts.

The top-selling new approval is likely to be Merck & Co.’s subcutaneous formulation of pembrolizumab plus berahyaluronidase alfa (Keytruda Qlex) for various solid tumours.

Pembrolizumab, a landmark PD1 inhibitor that was first approved in 2014, unleashes immune cells on cancerous cells. Berahyaluronidase alfa is an endoglycosidase enzyme that facilitates the injection of the antibody, temporarily breaking down the subcutaneous extracellular matrix to improve the antibody’s permeation and absorption. Drug developers have been using the hyaluronidase enzyme as a spreading agent for decades, but this is the first green light for this engineered variant of the protein. Merck’s combination as a result counts as a novel approval.

Pembrolizumab is forecasted to pull in around $32 billion in 2025, making it the top-selling cancer drug (and third-highest selling drug overall). Analysts at Evaluate expect the subcutaneous product to contribute $9.3 billion in peak sales.

Akeso Biopharma secured an approval for its PD1 blocker penpulimab (Penpulimab), bringing the number of available PD1/PDL1 antibodies up to 12.

2025 also saw the approval of two new antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), a modality made up of tissue-selective antibodies fused to potent cell-killing drugs. Daiichi Sankyo’s TROP2-targeted ADC datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway) secured a thumbs up for the treatment of hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer following endocrine-based therapy and chemotherapy.

Evaluate forecasts peak sales of $5.4 billion for the ADC, assuming a possible additional approval in a bigger non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cohort. Gilead and Immunomedics’s first-in-class TROP2-targeted ADC sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy), first granted accelerated approval in 2020, is on track to earn $1.4 billion in 2025.

The FDA also granted an approval to AbbVie’s first-in-class c-Met-targeted ADC, elisotuzumab vedotin (Emrelis). The microtubule-inhibitor-loaded antibody is approved for non-squamous NSCLC with high c-Met protein overexpression.

Regeneron’s linvoseltamab (Lynozyfic) adds a new bispecific T cell engager to the fold. Linvoseltamab binds BCMA on B cells and CD3 on T cells to drive B cell depletion for the treatment of multiple myeloma. It is the third BCMA × CD3 bispecific to market, and the 10th bispecific T cell engager.

On the kinase inhibitor front, the FDA granted a rare novel–novel combination approval for two previously experimental agents. Verastem’s avutometinib plus defactinib (Avmapki Fakzynja Co-Pack) combines a MEK inhibitor and a FAK inhibitor for the treatment of KRAS-mutated recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

Defactinib is the first FAK inhibitor to secure a green light. The agency has approved several other MEK inhibitors. The FDA has counted these two novel kinase inhibitors as a single new drug approval.

“More people should be open to novel–novel combinations,” Verastem CSO Jonathon Pachter told Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.

Jazz Pharmaceuticals’ first-in-class activator of mitochondrial caseinolytic protease P (ClpP) dordaviprone (Modeyso) secured an accelerated approval for patients with diffuse midline gliomas that harbour H3 K27M mutations who have progressive disease following prior therapy. ClpP chews up mitochondrial proteins, and in this cancer its activation is hypothesized to induce the integrated stress response, apoptosis and the release of metabolites that reverse the proliferative effects of H3 K27M mutations.

First-in-class, with big unmet needs

Non-oncology CDER approvals also added two mega-blockbuster contenders with first-in-class mechanisms for new disease indications.

Insmed’s brensocatib (Brinsupri) is the first DPP1 inhibitor to market for bronchiectasis, showcasing the potential for neutrophil-targeting drugs in inflammatory lung diseases.

Bronchiectasis is a chronic disease of the lungs that results in excessive mucus production, persistent cough and widening of the airways. It affects 350,000–500,000 people in the USA, and until this year the only treatment options were physical therapy to promote mucus clearance and antibiotics to tackle associated respiratory infections. The disease has been linked with overactive neutrophils, innate immune cells that release antimicrobial peptides called neutrophil serine proteases (NSPs) to kill invading pathogens. The DPP1 inhibitor brensocatib dampens NSP production, disarming these inflammatory proteases while sparing other neutrophil effector functions.

“It’s a hopeful time — to be able to tell patients that there are things on the horizon that may really help them,” Doreen Addrizzo-Harris, a pulmonologist at NYU Langone Health who was involved in the clinical trials of brensocatib, told Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.

Analysts forecast peak sales of $6.3 billion for the drug, assuming further approvals in other neutrophil-mediated diseases. In December the company discontinued development in chronic rhinosinusitis, however, after the drug failed to reduce nasal inflammation in that setting.

Vertex’s NaV1.8 sodium channel inhibitor suzetrigine (Journavx) provides a much-needed non-opioid painkiller option for acute pain. Drug developers have been working to inhibit NaV sodium channels since the 2000s, when researchers found that gain-of-function mutations in the NaV1.7 channel in humans can lead to persistent pain problems and that loss-of-function mutations can prevent the perception of pain. NaV1.7 inhibitors have disappointed in the clinic, but Vertex persevered with the related NaV1.8 channel.

“This is the first medicine that is specifically designed to only affect pain,” Paul Negulescu, senior vice president of research at Vertex, told Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. “Suzetrigine is the beginning, but it’s not the end. It’s a great first step in this new class of medications.”

Analysts forecast peak sales of $3.7 billion for the drug, citing the need for non-addictive painkillers and its broader opportunity in chronic pain indications. But there are headwinds. Suzetrigine was approved on the basis of its non-inferiority to acetaminophen–opioid combinations in acute pain following some surgical procedures, but its comparability in other acute pain settings remains unclear. It also has a much higher price tag than decades-old agents that are available as generics. And the drug’s efficacy in chronic pain settings remains to be seen. Phase III development of suzetrigine in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy is ongoing, but the drug failed in a trial in lumbosacral radiculopathy.

Vertex discontinued its development of the follow on Nav1.8 inhibitor VX-993 for acute pain after that agent failed in a phase II trial later in the year.

Other first-in-class agents also provide important additions to the pharmaceutical tool box, but come with lower sales expectations.

GSK’s gepotidacin (Blujepa) for example provides a much needed new oral antibiotic option. Gepotidacin, like quinolone-based antibiotics that have been in use since the 1960s, inhibits bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. But it uses a different scaffold and binds the target at a different site, giving it a first-in-class antibiotic moniker. The FDA first approved it in May for uncomplicated urinary tract infections (uUTIs) in female adults and paediatric patients 12 years of age and older. In December the FDA approved it for gonorrhea.

Innoviva Specialty Therapeutics’ zoliflodacin (Nozolvence), another structurally distinct inhibitor of bacterial type II topoisomerases, also secured an FDA approval for gonorrhea. The phase III trials of zoliflodacin were funded and carried out by Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP), a publicly funded not-for-profit that plans to make the drug available and accessible globally. Innoviva acquired the drug by buying Entasis Therapeutics, a spin-out of AstraZeneca.

Proven targets, new indications

Kinase inhibitors continue to push into inflammatory and immune diseases, led by agents that act on BTK. BTK inhibitors were first approved for the treatment of blood cancers based on their ability to kill malignant B cells, but they can also be used to modulate the activity of these immune cells. This year Sanofi snagged a first approval for its rilzabrutinib (Wayrilz) for immune thrombocytopenia, an autoimmune blood disorder. Novartis got a green light for its remibrutinib (Rhapsido) for chronic spontaneous urticaria, also known as chronic hives.

Analysts forecast peak sales of $2.1 billion for remibrutinib, which is still in clinical development for multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, hidradenitis suppurativa and food allergies. They expect peak sales of $900 million for Sanofi’s rilzabrutinib.

The agency by contrast rejected Sanofi’s BTK inhibitor tolebrutinib for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

Boehringer Ingelheim’s nerandomilast (Jascayd) became the first PDE4 inhibitor for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory PDE4 inhibitors have been approved for other indications, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and psoriasis. Boehringer now adds a nod for IPF, a chronic and fatal lung disease that affects up to 3.6 million people worldwide. Nerandomilast preferentially inhibits the PDE4B family member to dampen profibrotic processes and inflammation in the lung.

It is the first new drug to market for IPF in over 10 years, following on from the 2014 FDA approvals for Boehringer’s multikinase inhibitor nintedanib (Ofev) and the antifibrotic pirfenidone (Esbriet), now marketed by Legacy Pharma.

A new modality

LIB Therapeutics scored a first approval for an adnectin-based therapy, with its PCSK9-blocking lerodalcibep (Lerochol).

Adnectins are biologic agents that are built with fibronectin type III domains, scaffold proteins that facilitate cell–cell interactions and that can bind various ligands. Researchers have for decades held that adnectins can serve as antibody mimetics, offering exquisite selectivity for extracellular and cell-surface targets while offering smaller, simpler and more stable structures than conventional monoclonal antibodies.

LIB adopted this technology to develop the latest blocker of PCSK9, a well-validated lipid-lowering target. PCSK9-targeted antibodies have now been on the market for 10 years. Uptake of these agents has yet to live up to once-high hopes, in part because of the costs of the antibodies and the inconvenience of their subcutaneous dosing compared with generic lipid-lowering pills. LIB hopes that its lerodalcibep — a self-administered, once-monthly subcutaneous injection with extended room-temperature stability — will have a convenience edge.

Oral small-molecule PCSK9 inhibitors could be coming soon, however. Merck & Co. is expected to file its once-daily enlicitide for FDA approval in April. The FDA has granted the drug a CNPV, and so it could be due for a speedy review. If approved, the company says it plans to make the drug “broadly available as an affordable option for American patients”.

Cluster analysis

Patients with hereditary angioedema (HAE) meanwhile gained access to three new drugs.

HAE is a rare genetic swelling disorder that is caused by deficiencies or dysfunction of the C1 inhibitor, a protein that regulates the activity of multiple serine proteases. The lack of C1 inhibitor results in increased activity of complement proteases, plasma kallikrein and the coagulation proteases factor XIa, XIIa and XIIf.

CSL’s Behring’s newly approved prophylactic antibody garadacimab (Andembry) takes aim at activated factor XII to prevent disease attacks. Ionis’s antisense oligonucleotide donidalorsen (Dawnzera) targets prekallikrein to also prevent disease attacks. Kalvista’s small-molecule plasma kallikrein inhibitor sebetralstat (Ekterly) is by contrast approved for the treatment of acute attacks.

These new drugs step into a crowded HAE market, however, and are taking on established preventative and acute options that act at various nodes in the pathologic pathway.

Patients with primary immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) at risk for disease progression gained access to two new therapies. IgAN is an immune-mediated kidney disease, in which immunoglobulin A (IgA)-containing immune complexes accumulate in the kidney. It causes progressive loss of kidney function, and can lead to kidney failure. Otsuka’s sibeprenlimab (Voyxact) is a first-in-class APRIL-targeted antibody for the disease, dampening IgA production to reduce proteinuria in patients. Novartis’s newly approved atrasentan (Vanrafia) is an endothelin receptor antagonist, lowering glomerular pressure and inflammation in the kidneys.

Vera Therapeutic’s atacicept, a BLyS and APRIL inhibiting fusion protein, is under FDA review for IgAN too, with a decision due in 2026.

Non-profit gene therapy

CBER continues to notch up additional gene therapy approvals. This includes a first approval for a non-profit organization, with Fondazione Telethon ETS’s regulatory win for etuvetidigene autotemcel (Waskyra) for the treatment of Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (WAS).

WAS is a rare genetic disease, caused by mutations in the WAS gene that lead to abnormal platelet formation. Etuvetidigene autotemcel is an ex vivo gene therapy that uses a lentiviral vector to add the WAS gene sequence to patient-derived haematopoietic stem cells, restoring platelet function. The gene therapy originated from a 2010 partnership between the Fondazione Telethon non-profit, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy and GSK, and has shown durable efficacy. When GSK struggled with the commercialization of gene therapies, it licensed the experimental etuvetidigene autotemcel to Orchard Therapeutics. Orchard licensed it to Fondazione Telethon in 2022.

Fondazione Telethon will work with Orphan Therapeutics Accelerator, a non-profit biotech, to provide patients in the US with access to the gene therapy. The partners expect to treat fewer than 10 patients per year with the gene therapy in the US. Pricing negotiations are ongoing. The gene-therapy community is watching closely to see how the non-profit model will work.

“As an academic scientist, I would say I underestimated the burden of filing and maintaining a drug on the market,” Alessandro Aiuti, deputy director of clinical research at San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, told Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. Aiuti helped to steward the gene therapy to approval.

The FDA also approved Abeona Therapeutics’ prademagene zamikeracel (Zevaskyn), a first cell-sheet-based gene therapy for a severe skin disease. Prademagene zamikeracel is made from skin cells that have been biopsied from patients, transduced ex vivo to carry a gene that encodes type VII collagen, and then grown into credit-card sized sheets of cells that are grafted on to wounds. It is approved for the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB), a rare genetic skin disease caused by mutations in the gene that encodes type VII collagen. Patients with the disease have fragile skin that tears and blisters easily.

The FDA in 2023 approved Krystal Biotech’s beremagene geperpavec (Vyjuvek), a topical, redosable type VII collagen gene therapy that speeds up wound healing in patients with DEB.

Precigen’s zopapogene imadenovec (Papzimeos) is a first immunotherapy for a rare viral disease called recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP). RRP is caused by human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and results in non-cancerous growths in the airway. Zopapogene imadenovec consists of a non-replicating gorilla adenovirus vector loaded up with genes from HPV 6 and 11, triggering a T cell response against HPV to clear these growths.

CBER also granted full approval to two new COVID-19 vaccines. Moderna’s mNexspike, a next-generation mRNA vaccine, uses one-fifth the amount of mRNA per dose compared with the company’s earlier Spikevax and codes for only parts of the spike protein. Analysts forecast sales of over $3.2 billion for the vaccine.

Rejection letter transparency

In another policy change at the FDA, the agency started releasing partially redacted complete response letters for rejected drugs. As of 31 December, it listed 43 applications that were rejected in 2025, including new drugs (Table 3), supplemental filings, generics and biosimilars filed with either CDER or CBER.

Scholar Rock received a complete response letter for its apitegromab, an anti-promyostatin antibody. Scholar Rock has developed the muscle-building antibody for spinal muscular atrophy, but the agency rejected it due to issues at a third-party fill-finish facility. Scholar Rock plans to refile the drug once the manufacturing issues are resolved.

Regeneron received a second complete response letter for its odronextamab, a CD20 × CD3 targeted bispecific for follicular lymphoma. This rejection too was due in part to issues at the same fill-finish facility.

Stealth Bio received a complete response letter in May for its elampretide, a mitochondrial cardiolipin binder for the treatment of Barth syndrome. The FDA said at the time that the submitted dossier did not show sufficient evidence of effectiveness for either full or accelerated approval. Stealth resubmitted a new dossier months later, seeking approval on the basis of a different surrogate endpoint, and secured approval in September.

The agency also rejected Replimune’s vusolimogene oderparepvec, which could have become the first new oncolytic virus to market since the 2015 approval of Amgen’s talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic). A trial of vusolimogene oderparepvec in combination with the PD1 blocker nivolumab in patients with melanoma showed a numerically higher response rate than historical control rates, but the FDA’s complete response letter notes that the heterogeneity of the patient population in this trial precludes interpretation of these results. The trial also did not isolate the effects of the therapeutic virus from those of the PD1 blocker.

Replimune has since resubmitted vusolimogene oderparepvec for approval. A decision is due in April.

A new year

Multiple novel drugs are up for potential first approvals next year (Table 4).

Arvinas and Pfizer’s oestrogen receptor (ER)-targeted vepdegestrant could become the first targeted-protein degrader to secure an FDA approval. The FDA has approved several selective oestrogen receptor degraders (SERDs), which induce conformation changes in the ER to drive degradation. Vepdegestrant is a two-armed small molecule PROTAC that binds the receptor with one arm and a piece of the proteasomal machinery with the other to induce degradation. The drug has however struggled in trials to differentiate itself from approved and investigational SERDs, and Arvinas and Pfizer are looking to out license the first-in-modality agent.

If approved vepdegestrant would nevertheless validate targeted degraders. Drug developers expect that the modality and related molecular glue degraders could yet unlock otherwise undruggable targets.

Denali Therapeutics expects an approval for its tividenofusp alfa, an enzyme replacement therapy for Hunter syndrome. Takeda’s idursulfase (Elaprase), an iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS) enzyme replacement therapy, has been approved since 2006 for this disease but has poor penetration into the brain and cannot address the neurological symptoms associated with the disease. Tividenofusp alfa consists of the IDS protein fused to an Fc fragment that binds the transferrin receptor, shuttling the biologic into the CNS.

Regenxbio could also get an approval for its clemidsogene lanparvovec, a gene therapy that is injected into the CNS for the treatment of Hunter syndrome.