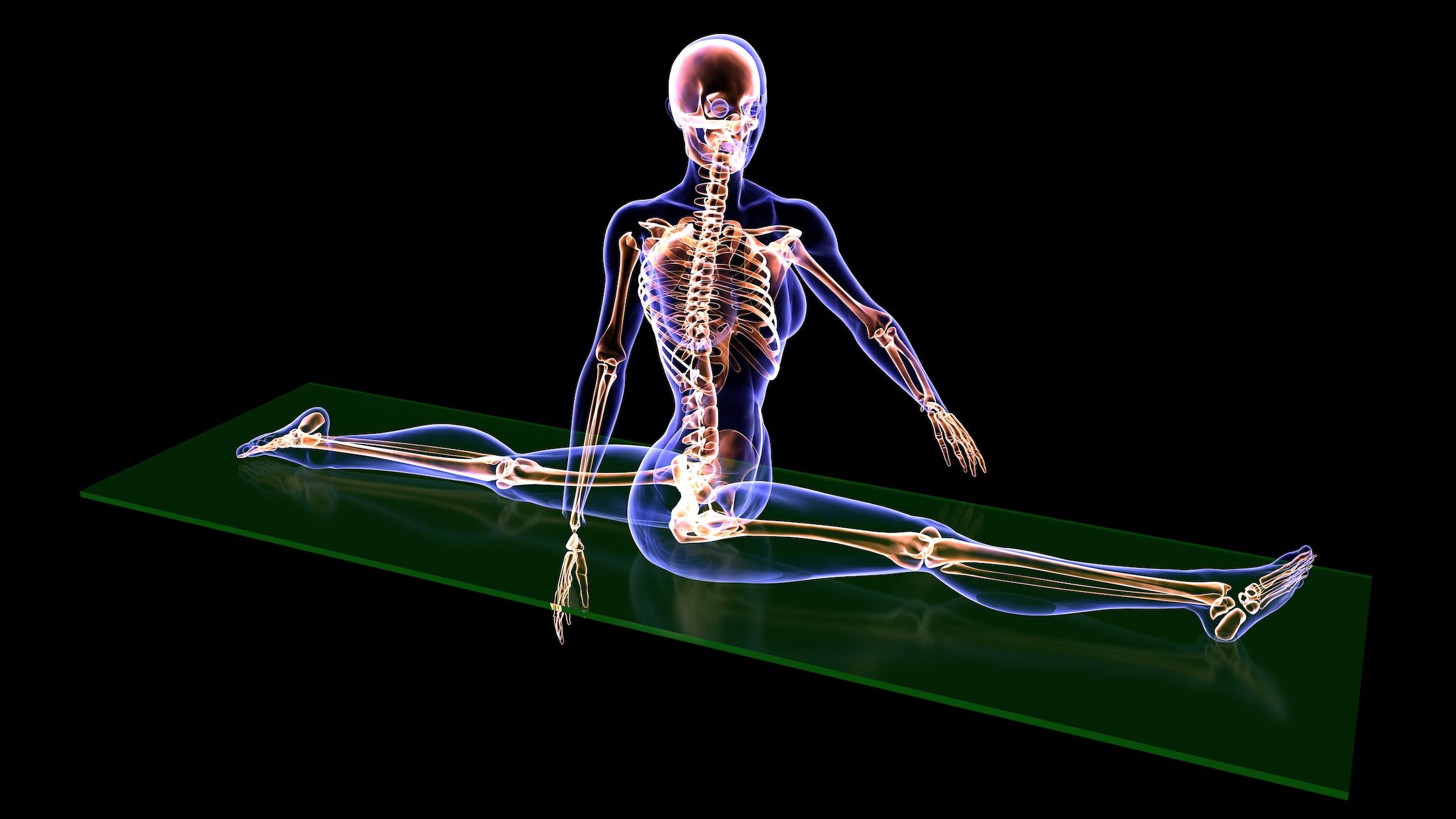

It’s no secret that babies have more bones than adults: Whereas newborns can have 275 to 300, with smaller bones fusing and hardening to create larger bones as the children grow older, most adults have only 206. (Having tinier, softer bones…

It’s no secret that babies have more bones than adults: Whereas newborns can have 275 to 300, with smaller bones fusing and hardening to create larger bones as the children grow older, most adults have only 206. (Having tinier, softer bones…