This study included thirty-two patients who presented with symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis. Among them, twenty patients (62.5%) had objectively confirmed delayed gastric emptying (GP group), while twelve patients (37.5%) had normal gastric emptying (GP-like group). The majority of patients were females (81.3%) with a mean age of 40.59 ± 11.13 years, aligning with the findings of Navas CM et al.; they reported a predominance of middle-aged females [7].

In this study, no significant differences were observed between the GP and GP-like groups regarding age, sex, type of DM, DM treatment and complications, HbA1c (%), smoking status, or comorbidities. Although not statistically significant, the GP group had a higher prevalence of diabetic nephropathy than the GP-like group (12 cases vs. 3 cases, p = 0.055). These findings are consistent with Bharucha et al., who reported delayed gastric emptying in 36% of their cohort (46 patients). They found no associations between gastric emptying and demographic features (age, sex, and BMI), smoking status, type and duration of DM, use of insulin, HbA1c (%), or the presence of diabetes-related complications [8].

Similarly, Navas CM et al. found no correlation between gastric emptying and the referring symptom, duration of DM, HbA1c (%), or diabetes complications, though they observed an association between more severe gastric emptying delay and insulin dependence (p = 0.046) [7].

Chedid V et al. found that 19.4% of symptomatic patients had delayed gastric emptying. They concluded that gastric emptying is not related to diabetes control nor the duration of diabetes [9]. In contrast, Izzy M et al. reported an increased incidence of gastroparesis in patients with worse HbA1c (%) [10]. Additionally, Bharucha et al. found that patients with delayed gastric emptying had a longer duration of DM, higher HgbA1c level, and higher prevalence of retinopathy [11]. This aligns with the findings of Hyett et al., who also found that patients with GP had a longer duration of DM when compared to patients with GP-like symptoms [12].

In this study, post-prandial fullness was the dominating symptom, while the most dominant GCSI subscale was bloating/distension. This contrasts with Navas CM et al., who reported nausea and upper abdominal pain as the most common symptoms, followed by vomiting and early satiety [7]. Similarly, in Chedid V et al. study, the most common presenting symptom was nausea and vomiting [9]. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in population characteristics, underlying comorbidities, and potential regional variations in symptom perception and reporting.

In this study, significant positive correlations were observed between the T1/2 of gastric emptying and several parameters including serum creatinine, AST, total GCSI, average GCSI, nausea/vomiting subscale, and vomiting severity (p = 0.024, 0.006, 0.004, 0.009, 0.033, 0,030, respectively). A significant negative correlation was also found between the T1/2 of gastric emptying and hemoglobin levels (p = 0.004). These findings may suggest an association between delayed gastric emptying and the presence of fatty liver and diabetic nephropathy. The inverse relation between hemoglobin levels and the T1/2 of gastric emptying may reflect nutrient deficiencies in gastroparesis patients due to poor food intake. This is supported by Parkman HP et al.’s study which demonstrated that many patients with gastroparesis consume diets deficient in calories, carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals [13].

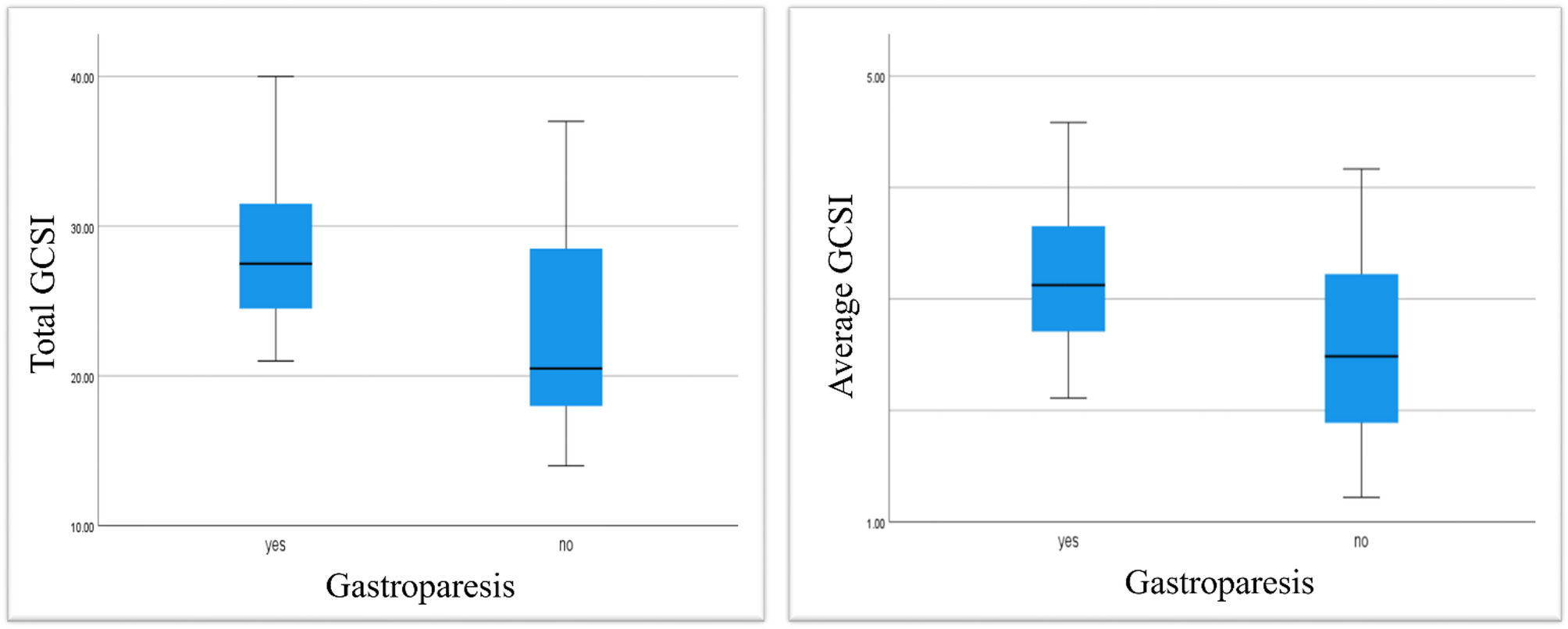

In this study, symptoms of GP were significantly more severe in the GP group compared to the GP-like group according to the total GCSI (p = 0.021) and the average GCSI (p = 0.048). Logistic regression analysis identified the total GCSI score as an independent predictor of delayed gastric emptying in gastric scintigraphy (OR 1.153, 95% CI (1.009–1.317), p = 0.036). A total GCSI greater than 23 demonstrated a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 66.7% for identifying delayed gastric emptying (AUC 0.746, p = 0.016, 95% CI 0.545–0.947). These findings should be taken with caution, given the wide confidence interval and the small sample size. It may not apply universally before validation in larger cohorts.

Cassilly DW et al. found that nausea, inability to finish a normal-size adult meal, and post-prandial fullness sub-score were positively correlated to gastric retention at 2 h (p = 0.09 and p = 0.005, p = 0.01 respectively). The correlation between the total GCSI and gastric retention was significant at 2 h (correlation coefficient 0.144, p = 0.03) but not at 4 h (correlation coefficient 0.040, p = 0.55). Importantly, their logistic regression showed that none of the GCSI components independently predicted the diagnosis of gastroparesis, leading to the conclusion that the GCSI may not be a reliable predictor of gastroparesis among symptomatic patients [14]. Several other studies have similarly failed to identify a significant correlation between upper gastrointestinal symptom scores and gastric emptying [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Another recent study assessed whether the GCSI score could help in the diagnosis of gastroparesis, but did not find a clear diagnostic threshold [21]. Indeed, the main difference between the current study and the previous studies is that the current study only assessed diabetic patients, while previous studies mainly mixed diabetic and non-diabetic patients with gastroparesis. Interestingly, nausea and vomiting remained the symptoms with the strongest association with T1/2.

The management of gastroparesis is challenging and requires a multi-disciplinary approach. Potential mechanisms of response to medical treatment include: improved gastric motility due to better glycaemic control, neuro-modulatory effects of prokinetic agents, and discontinuation of DPP-4i/metformin combination that may contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms. In our study, 55% of cases responded to a three-month course of medical treatment. Navas CM et al. found that about 40% of cases reported improvement following anti-emetic therapy with domperidone and metoclopramide; however, they didn’t use GCSI to measure the severity of symptoms [7]. In a single-center cohort of 115 cases of GP (16 of whom had DM), domperidone therapy for an average of three months led to improvement in 69 patients (60%), and moderate improvement in 45 patients (39%), as assessed by the Clinical Patient Grading Assessment Scale [22]. In a study by Parkman HP et al.., including 48 GP patients, 81% of patients showed improvement after domperidone therapy [23]. Another study, which included 262 cases of GP diagnosed by solid GS (32% of whom had DM), assessed symptoms using the GCSI before and after 48 weeks of medical treatment. In this cohort, 15% of patients achieved a ≥ 50% improvement in their GCSI score [24].

In the current study, Responders were significantly older than those in the refractory group (p = 0.046). This is consistent with findings from Parkman et al.., who observed that patients < 45 years old had a significantly lower clinical response (1.18 ± 1.05; n = 22) compared to patients ≥ 45 years old (1.88 ± 0.80; n = 27; p < 0.05) [23]. Similarly, Pasricha PJ et al. reported that older age (≥ 50 years) was associated with the best outcome, with an odds ratio for improvement of 3.35 (CI:1.62–6.91, p = 0.001) [24]. These observations may be attributed in part to greater patient satisfaction in older individuals, and the subjective nature of symptom assessment scores.

In our study, Responders also had significantly lower initial total and average GCSI scores (p = 0.012, p = 0.025 respectively). This finding contrasts with the study by Pasricha et al.., where higher total GCSI scores were associated with a more favorable response to treatment after 48 weeks (OR = 2.87, CI: 1.57–5.23, p = 0.001) [24]. This discrepancy may reflect the unique profile of our cohort, in which severe symptoms are more likely to represent greater disease burden and therapeutic resistance. More severe symptoms may be indicative of greater autonomic dysfunction, and significant gastric dysmotility limiting the efficacy of standard medical treatment. This interpretation is further supported by findings from Amjad et al., where the presence of peripheral neuropathy was associated with treatment failure [25]. Additionally, the pathophysiological differences between diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis may explain the divergence in findings between our study and Pasricha et al.’s, where two-thirds of patients were non-diabetic. It is possible that in idiopathic gastroparesis, symptom severity reflects a component of visceral hypersensitivity, which might respond differently to therapy compared to the predominant motility dysfunction seen in diabetic gastroparesis. These findings have important clinical implications. In diabetic gastroparesis, severe symptoms may indicate a higher likelihood of refractoriness to standard medical therapy. This suggests the need for stratified treatment approaches, where patients presenting with high symptom burdens may require alternative or more aggressive interventions, such as G-POEM to reduce unnecessary prolonged medical treatments in those unlikely to benefit.

In our study, a significantly greater HbA1c reduction (%) was reported in the responders’ group than those in the refractory group (p = 0.012). This underscores the potential role of glycaemic control in the management of gastroparesis and highlights the bi-directional relation between glycemia and gastroparesis. On one hand, gastroparesis worsens hyperglycemia due to poor oral intake and poor adherence to anti-diabetic medications, often due to post-prandial hypoglycemia. On the other hand, hyperglycemia itself has been shown to worsen gastroparesis [26]. While several studies have explored the impact of glycaemic control on GP severity, their findings have been inconsistent, highlighting the need for large-scale studies to investigate this relationship [27,28,29,30].

G-POEM is a promising new procedure for the management of refractory GP. According to the American Gastroenterology Association recommendations, G-POEM should be offered to adult patients with refractory gastroparesis who have gastric outlet obstruction been excluded by gastroduodenoscopy, have delayed gastric emptying in a solid gastric scintigraphy, and have moderate-to-severe symptoms preferably with nausea and vomiting as the dominant symptoms [6]. When performed by experienced endoscopists, G-POEM is generally safe, and complications are uncommon. However, serious complications have been reported like bleeding, perforation, capno-peritoneum, gastric ulceration, and dumping syndrome [31,32,33]. In the current study, only 4 of the 9 patients in the refractory group consented to undergo G-POEM. Sustained clinical improvement at 1 year was achieved in 2 cases only. While these results are preliminary and based on a small sample, they align with the existing literature. A systematic review assessing the 1-year clinical outcome after G-POEM reported a pooled clinical success rate of 61% (95% CI) and an adverse event rate of 8% [34].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study population was drawn from a single diabetes clinic, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, symptomatic patients who declined scintigraphy were not included, introducing potential selection bias. The relatively small sample size compared to other studies may also reduce the statistical power, particularly in the logistic regression analysis, making the results exploratory rather than conclusive. Another limitation is that upper endoscopy was not performed in all patients to exclude potential gastric outlet obstruction. Furthermore, blood glucose levels were not measured immediately prior to gastric scintigraphy. Given that hyperglycemia can delay gastric emptying, this could have influenced the gastric emptying parameters. Additionally, the use of gastric emptying T1/2 as the primary scintigraphic parameter, rather than the standard 4-hour retention values, is another limitation. The follow-up period was limited to three months, which was sufficient for short-term assessment of symptom response but may not fully capture the fluctuating nature of gastroparesis. Future studies are needed to assess the long-term outcomes and to determine whether patients in the GP-like group eventually develop gastroparesis. Another limitation of this study is the lack of a validated Arabic version of the GCSI questionnaire. While we verbally translated the questionnaire to facilitate patient understanding, the absence of a standardized linguistic and cultural validation process may have affected the consistency of symptom scoring. Future studies should consider using a formally validated Arabic translation to improve the accuracy of patient-reported outcomes.