Over the past few thousand years, humans have concocted ways to harvest ever more energy, whether from food production or from different sources of mechanical, chemical or electrical energy. The power of humans, beasts, wind, water, wood and more transformed our environment. The aim was often to improve human lives — at least some human lives. Many of these energy systems had large impacts, but they remained mostly local, the widespread extinction of large fauna notwithstanding.

Then, in the 18th century, humans began using industrial quantities of the densely concentrated energy stored in fossil fuels, releasing organic carbon that had been locked away for millions of years. As the use of fossil fuels began to rise, the gases they produced accumulated in the atmosphere. Initially, the environmental impacts of this Industrial Revolution were, like the prior effects of human energy use, largely local: poisoned waterways and smog-filled urban areas. But that changed as humanity’s vast energetic capabilities expanded. It wasn’t just that the local impacts grew larger — the economy grew on the back of this new energy abundance and living standards improved. A truly global, distributed impact of our hunger for energy emerged.

The Extended Biosphere

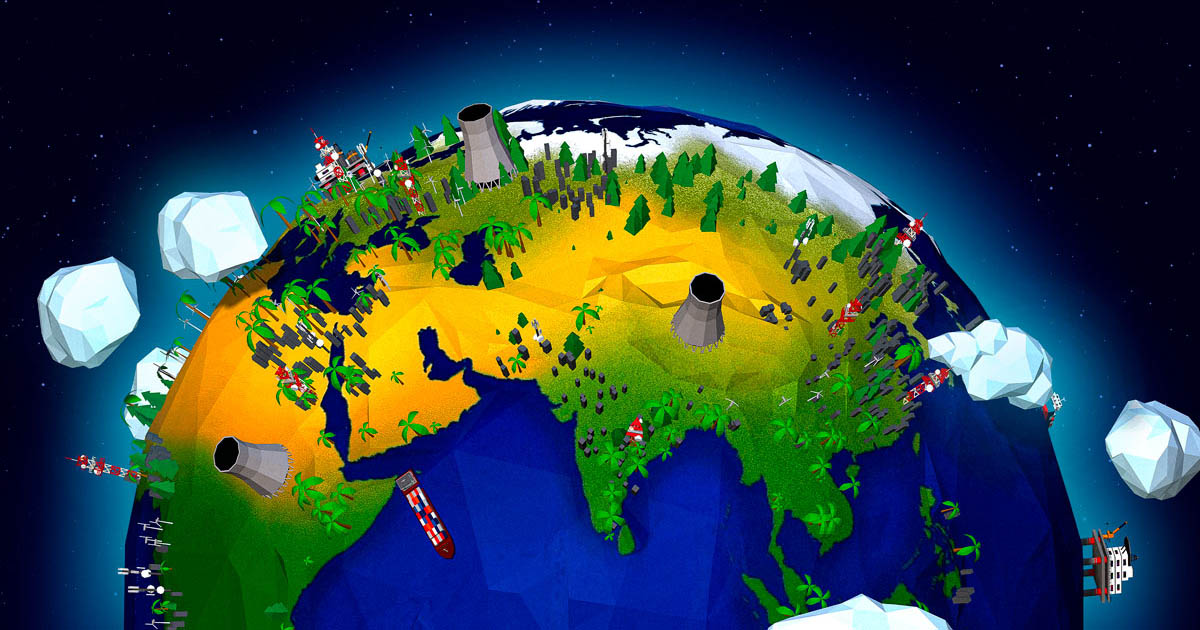

No period in our history compares to the Great Acceleration that followed World War II, an explosion in globalized human activity driven by population expansion, innovations in technology and communications, and advances in agriculture and medicine. The Great Acceleration is reflected in the rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide, water use, manufacturing production, ozone depletion, deforestation, pollution and global GDP, which brought welcome increases in lifespan and living conditions for billions of people. Never before had our reach been truly planetary, extending far beyond local or even regional environments to dominate the entire biosphere of Earth.

We have used the biosphere as an infinitely large repository for extraction of resources and deposition of waste. In this way, we are similar to other species: We harvest resources, process them biochemically and expel the by-products. There are two primary differences. Our access to energy amplifies the scale and speed of what we do. And importantly, we are now cognizant of the planetary transformation we have initiated.

Over the past few decades, advances in Earth-system monitoring and modeling mean we understand this impact and the ways in which it threatens our survival. For more than a year, the average temperature of the planet has been more than 1.5 degrees Celsius hotter than the preindustrial average because of our activities, and it is having a noticeable impact on our lives. While it is true that no one decided to heat the planet — there was no purpose beyond the universal and innate biological drive to harness energy — the changes we make to the biosphere are now made knowingly, and thus purposefully.

This makes us something very different from the cyanobacteria that once remade the biosphere. We are planetary actors with purpose. That means we must bear responsibility. Thrillingly, it also means we have the potential to effect positive change.