Former Industrial Light & Magic artists join ILM.com to reflect on bringing the pre-digital cinema classic to life.

By Clayton Sandell

During the summer of 1985, The Goonies hit movie screens and became an instant audience favorite. The timeless adventure tale follows a group of kids on a quest to discover One-Eyed Willy’s hidden pirate treasure, avoid a trio of ruthless family crooks, and save their homes (and way of life) in the “Goon Docks” of Astoria, Oregon.

While it’s not considered a massive visual effects film, part of the enduring charm of The Goonies is thanks to around 20 shots created by Industrial Light & Magic. Forty years later, four former ILM veterans share their memories about working on the celebrated classic.

ILM’s Michael McAlister was hired as the film’s visual effects supervisor, his first time in the role after working as an effects cameraman on projects including E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984).

Dave Carson brought extensive ILM experience to the role of visual effects art director on The Goonies, with credits including Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Dragonslayer (1981), and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984).

The work of The Goonies matte painter and fine artist Caroleen “Jett” Green has appeared in dozens of films, including Willow (1988), Ghostbusters II (1989), and Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999).

Before a fruitful run as a visual effects supervisor, Bill George helped build a number of iconic models for films including Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Blade Runner (1982), and Explorers (1985).The Goonies was directed by Richard Donner (Superman [1978], Ladyhawke [1985]) from a story by Steven Spielberg and a screenplay by Chris Columbus. Frank Marshall and the now president of Lucasfilm, Kathleen Kennedy, were among the producers.

MICHAEL McALISTER, VISUAL EFFECTS SUPERVISOR: Number one, Dick Donner was such a good man. His personality was so big, and he spoke with a booming voice, and he was just confident and gentle and kind. I was really impressed with him. It was a real joy to be around him. I also had good crews at ILM, and the experience of being on location in Astoria, Oregon, which is absolutely stunningly beautiful, was delightful.

DAVE CARSON, VISUAL EFFECTS ART DIRECTOR: It had so many effects shots in the first draft. I remember being in a meeting in Burbank early in the production. I don’t think Dick Donner was even there. And we were talking about the effects. And I said, “Well, I think eventually there’ll probably be like 80 shots.” The blood drained from everybody’s faces. I could see that was not where they were headed. It still was a great project, but the number of shots kept dwindling. The first draft had skeletons that came to life. It was full of effects and fantastic stuff.

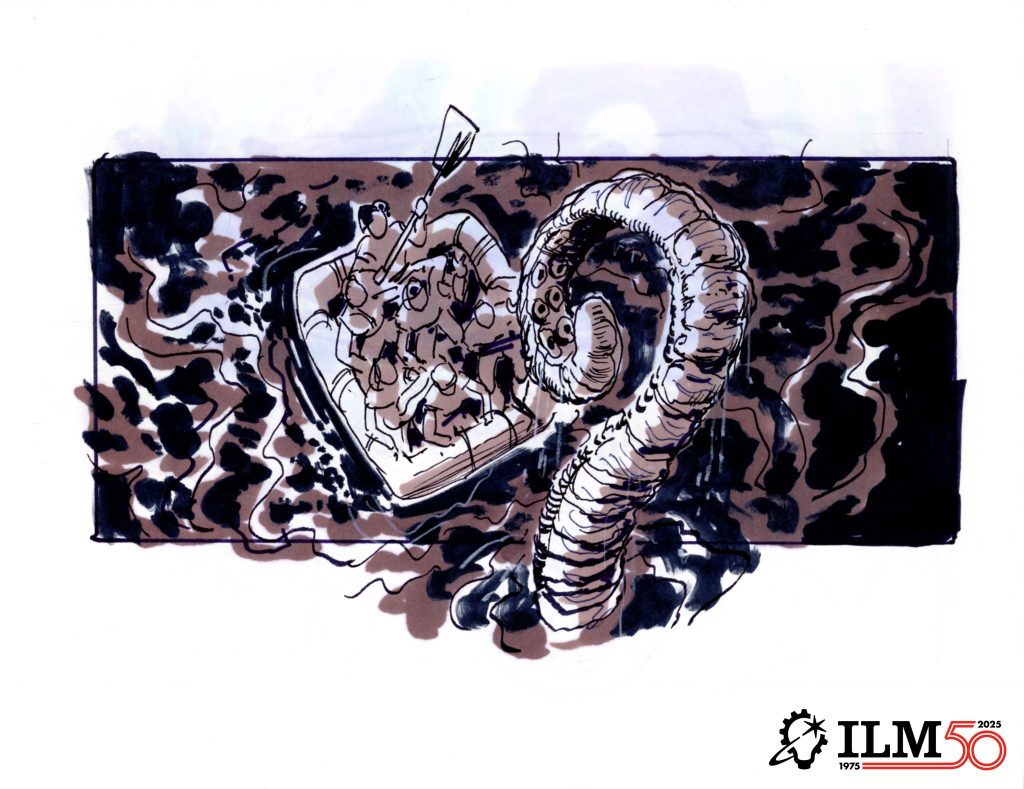

I started just by drawing scenes from the script. Nobody asked me to, but you can’t read that script without wanting to draw some of the scenes in it. J. Michael Riva was the production designer, and he was cranking out beautiful stuff. [Art director] Rick Carter made beautiful blueprints. They were establishing the look of this film, and it was great. From that point on, my actual work for the production was pretty much taking established background plates and indicating where the effects would go. There wasn’t too much pie-in-the-sky stuff. I did a bunch of storyboarding of the sequence where the kids run into the cove, and they see some skeletons and they get on the ship.

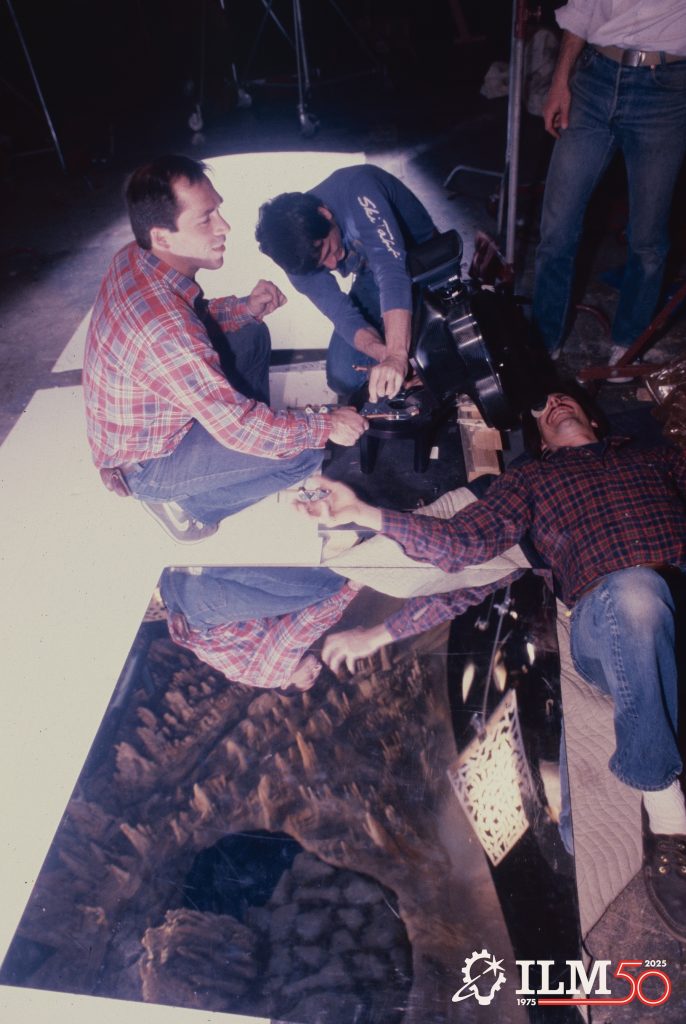

The ILM Model Shop built a highly detailed scale version of One-Eyed Willy’s sailing ship, the Inferno. Under the supervision of Barbara Gallucci, Bill George led a model-making team that included Randy Ottenberg and Chuck Wiley. ILM had plenty of previous experience with model spaceships, but building a wooden pirate galleon was something the crew had to learn from scratch.

BILL GEORGE, CHIEF MODELMAKER: I was really happy to be put on the project leading the construction of the miniature pirate ship. We wanted to do a good job and do something impressive that would get people talking. We put more into the model than we needed to. The production provided blueprints, which were amazing. We read books on building miniature ships and had the opportunity to do research and learn. We went to San Francisco Bay to study the Balclutha, which is a vintage wooden sailing ship. We studied all the details, the belaying pins, the rigging, the wood texture and wear. We wanted our model to look as authentic as possible.

We started with stanchions, very much the way you would build a boat. Those were covered in thin sheets of balsa wood. One of the big technical challenges on this was the rigging and the sails. Randy’s main focus was the sails. And, of course, there were no computer graphics that were advanced enough to do CG sails at that point. So the decision was made to make them out of a very, very fine silk, which would blow in the wind, and the silk was also great because it was transparent and pure white. Once again, we did some research. We found that we could use coffee and tea to stain the sails so they had a little bit of a warmer, aged color without stiffening the fabric. At the time Goonies came along, ILM had established itself as the visual effects house of choice for very successful films. Then there were all these films that Spielberg was producing, including The Goonies and Explorers and Back to the Future [1985], and all of them kind of funneled through ILM. It was a really exciting time because there was a whole diversity of interesting projects coming in.

MICHAEL McALISTER: It was unbelievably beautiful. But by the time the model was in the process of getting made, they decided to just go ahead and build the entire set on the soundstage. Which then meant that we didn’t need as many shots using the model.

BILL GEORGE: I was a little disappointed because we didn’t get to showcase it as much in the film. It was very backlit, and it was very far away, and I knew that the model could hold up. So it was a little bit of a disappointment. But I’m super proud of the model we built.

On deck, there’s even a little R2-D2 Easter egg. It was actually a casting from Star Wars. In the model shop, we had molds of the castings that go with the plug at the top of the X-wing starfighter. That’s what that was.

In 2023, the Inferno model was donated to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures by Richard Donner’s widow, producer Lauren Shuler Donner.

Production designer J. Michael Riva had the Inferno and a water-filled cavern built as a full-size, practical set on Stage 16 at the Burbank Studios (now Warner Bros.) in Southern California.

MICHAEL McALISTER: I’ll never forget it. It was the most impressive thing I’ve ever seen in my entire movie career, hands down. The first time I walked on the stage, here’s this full-size pirate ship. And every little glorious detail was just striking.

The director of photography, Nick McClean, was going back and forth to another stage at the same time as he was trying to light this pirate ship, and it wasn’t working out very well. He just didn’t have all that much time to be on Stage 16.

So he just turned to me and said, “Michael, light it for me,” and walked away. I was like, “Oh my God, I don’t know how to light a set!” I was freaking out because I didn’t want to come up short. I didn’t want to disappoint him, didn’t want to embarrass myself. And I remember thinking, “How would you light it if it was a miniature, and just scale it up?” So that’s what I did.

You just got thrown into something, and you had to figure it out. So Nick came back, and he looked at my lighting, and he was pretty happy. Only changed one thing. I learned something about confidence, and I learned something about lighting. It doesn’t really matter how big a thing you’re going to light. It’s all the same idea.

DAVE CARSON: It was an amazing thing to see. One morning on the set, there were probably a dozen of us all standing around drinking coffee, and Steven Spielberg walks in and he’s looking around. We’d met a few times, but he didn’t know me all that well. He says, “So what do you think?” I said, “There’s some great shots here,” and he says, “Oh yeah? Where?” I’m thinking, “Is he kidding me?” I was just trying to be conversational. But I decided I’d just follow through. So I walk over to the island with like twelve people following Steven, and I got down, just trying to find some interesting angles. I don’t know what he made of it all.

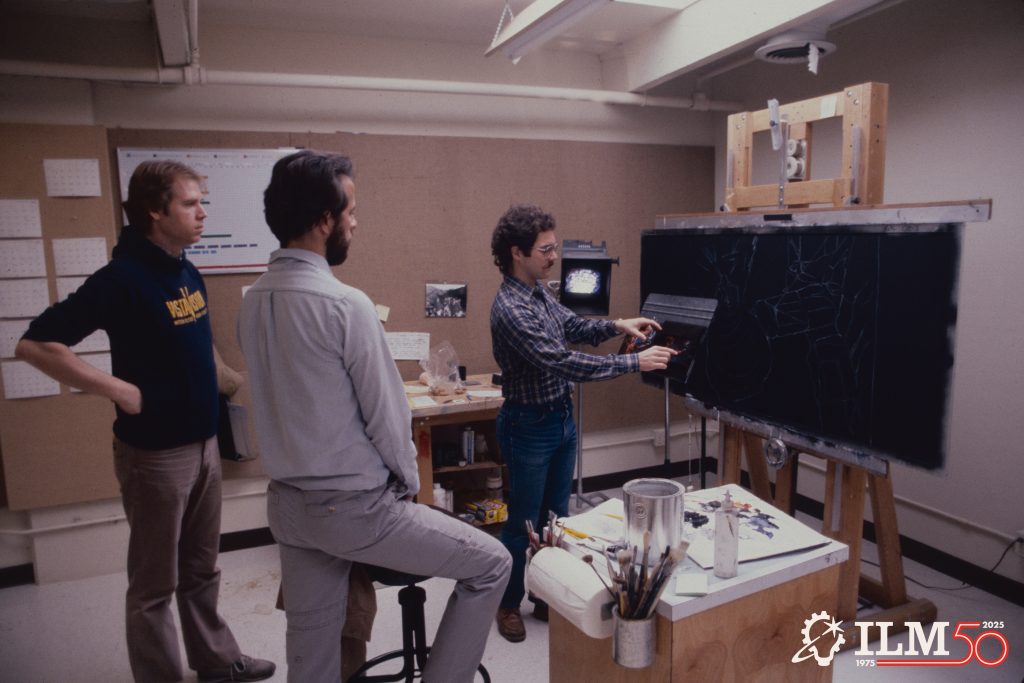

For wide shots of the Inferno, ILM artists Frank Ordaz and Caroleen “Jett” Green created matte paintings to help complete the illusion of a tall sailing ship rising beyond the limited height of the Burbank soundstage. Chris Evans served as matte painting supervisor.

CAROLEEN “JETT” GREEN, MATTE ARTIST: They had that big ship that they shot in a way that, at the last minute, they needed to extend the masts and add sails. We had to work quickly to make it all work perfectly.

The challenge was, we didn’t have much time, and the sails of a ship needed to have fluidity, an airy quality. Our matte painting extensions were static, so lucky for us the shots of the sails were only on for a couple of seconds.

I knew how to paint something realistically. What you also learn with matte painting is how to change lighting. You need to know what goes on with light, whether it’s indoors or outdoors, how it affects everything. If there’s a blue haze that’s moving in the shot, I might add some carefully mixed blue paint to match. It all got combined together.

I was an apprentice matte painter, learning the techniques and skills in order to become a great matte painter. I was working in a room with highly creative people, all excellent at what they do. I really wanted to keep up with these guys. And I told myself, well, “I’m just going to put in 150%.”

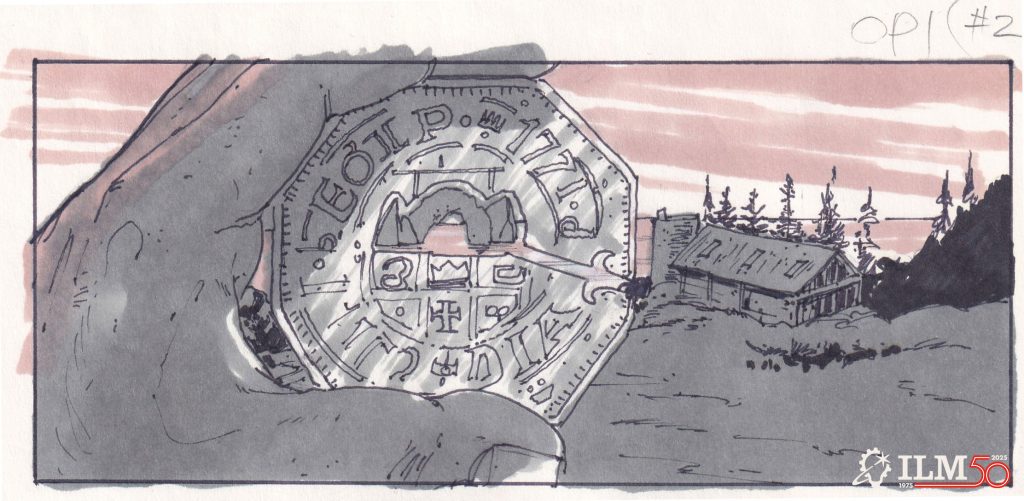

Another ILM contribution includes what might be considered an early example of a so-called “invisible effect.” Searching for their next clue, Mikey (Sean Astin) lines up a doubloon with cutouts to match rocks and a lighthouse in the distance. What appears to be a practical shot is actually a mix of multiple blue screen elements, background plates, and matte paintings. A complex rack focus helped complete the illusion.

DAVE CARSON: I remember the challenge at the time on the doubloon shot was they wanted the doubloon in focus and crisp up close. That means anything in the distance is going to be soft. So they had to pull off the rack focus in post-production.

MICHAEL McALISTER: One of the reasons that the shot was never attempted on set is because the rocks in the ocean didn’t exist. And they certainly didn’t exist to line up with the doubloon. So, based on that criteria, it automatically became a visual effect. And dealing with the rack focus was very challenging during that time because it was all optical printer composites, and you didn’t get good mattes out of blurry edges in the optical process. Today, it’s not an issue with all the CG capabilities and the compositing software, but it was a challenge at the time to get that right.

The organ chamber sequence – in which an incorrectly-played musical note causes part of the floor to fall away and reveal a treacherous cavern below – was achieved using five different matte paintings and a 16-by-20-foot miniature set featuring stalactites, pools of water, and fog. The original set was scaled down in size during pre-production, posing a challenge for creating the critical illusion.

MICHAEL McALISTER: The concept was supposed to be something that instantly communicated absolute death if you fell down there. That was one of the hardest things I’ve actually ever done in my career, creatively. And to this day, I’m not really happy with what that image communicates because it didn’t look like instant death to me. Richard [Donner] and [Steven] Spielberg didn’t ever complain to me about it, but I wasn’t really happy with that. It was supposed to be all misty and foggy, which made the lighting so diffuse that it was just really hard.

Four decades later, The Goonies continues to be treasured by fans young and old. In 2017, the Library of Congress added the title to the National Film Registry, which honors movies with cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance.

DAVE CARSON: It’s so funny. Of all the films I’ve worked on, when people find out I worked on The Goonies, a lot of times that’s the one that they’re impressed by. “Oh, you worked on The Goonies? I love that movie!” Yeah, it’s still a very popular film.

BILL GEORGE: The story reminded me of when I was a kid with my buddies, and we were looking for adventure on the street, throwing dirt clods, that kind of stuff. It really captured the essence of that in a really magical way. And I think for kids that age, they’re like, “Hey, let’s make this happen. Let’s find the treasure.” Goonies have a special place in our hearts.

CAROLEEN ‘JETT’ GREEN: We were all seriously into what we were doing: matte painting.

I considered many of the artists geniuses. Just a brilliant group of creatives. We would start painting at around 10 o’clock in the morning and go into the zone of silence for hours. Then we’d come up for air at the same time, lunchtime or later. At times, I would even stay until sunrise.

MICHAEL McALISTER: It is meaningful to me that there are a few films that I’ve worked on that are classics and will always be remembered. During The Goonies, I had a hunch about it because every kid dreams about finding a pirate ship and a pot of gold. I can’t take any credit for the fact that these movies have such legacies, but it’s nice to have been involved with a movie that made such a dent and endures.

When I first walked the halls of ILM, I realized I was walking among the best in the world at what they do. It was just such a privilege to be in that company, in the company of those artists, that level of creativity and expertise for so many years.

—

Clayton Sandell is a Star Wars author and enthusiast, Celebration stage host, and a longtime fan of the creative people who keep Industrial Light & Magic and Skywalker Sound on the leading edge of visual effects and sound design. Follow him on Instagram (@claytonsandell), Bluesky (@claytonsandell.com), or X (@Clayton_Sandell).