Contents

Key Takeaways 1

Introduction. 2

The Auto Industry Is Vital for U.S. Economic Competitiveness 3

China’s EV Competitiveness 5

China’s EV Mercantilism. 6

Chinese EV Makers Shouldn’t Be Allowed to Manufacture in America. 10

Conclusion. 13

Endnotes 14

The Trump administration rightly seeks to expand U.S. manufacturing, particularly in advanced industries such as aerospace, automotive, biopharmaceuticals, and semiconductors. As such, the administration is to be commended for notable successes in expanding U.S. manufacturing investment, touting as much as $5 trillion in new commitments.[1] But not all manufacturers are created equal. U.S. policymakers must be attuned to both the nature of the foreign direct investment activity America attracts, especially from Chinese manufacturers that have been the beneficiaries of aggressive mercantilist practices, and their efforts to enable Chinese techno-economic power.

The appeal of letting Chinese automakers sell in America as long as they produce here is an appealing one. It would expand jobs, compared with importing Chinese vehicles, and any announcements could be touted as a win by the administration. This is perhaps why, in a March 2024 speech, then-candidate Trump commented that, “I’ll tell [Chinese automakers] if they want to build a plant in Michigan, in Ohio, in South Carolina, they can, using American workers, they can.”[2]

As the Trump administration works through potential trade deals with a number of nations, it could potentially make permitting electric vehicle (EV) makers to build production facilities in the United States part of a grand bargain trade deal with China. China would benefit from this and the administration could use it as leverage for Chinese concessions.

But as attractive as this option might be in the short term, the administration should not allow Chinese EV makers—whether BYD, Nio, Xiaomi, or others—to construct manufacturing plants in the United States, especially when doing so would reward both Chinese mercantilist policies as well as Chinese EV firms’ gambit to circumvent the tariffs the United States has already sensibly imposed on them. This is principally because Chinese EV makers have benefitted considerably from aggressive mercantilist practices, and as such are fundamentally different from other foreign auto companies that manufacture and compete in the U.S. marketplace. Indeed, letting Chinese EV makers into the American vehicle market could be an ”extinction-level event” for the U.S. auto sector.[3]

This report explores why the U.S. auto industry is vital for American economic competitiveness. It then examines the competitiveness of Chinese EVs companies, explaining why a great deal of that competitiveness stems from Chinese government support through mercantilist policies such as substantial industrial subsidization and forced technology transfer. It concludes by enumerating the myriad specific rationales why Chinese automakers should not be allowed to manufacture in the U.S. market.

A robust automotive sector is crucial to the overall health of the U.S. economy. The sector has historically contributed from 3 to 3.5 percent of overall U.S. gross domestic product.[4] The industry supports a total of 9.7 million American jobs, or about 5 percent of total private sector employment. This includes approximately 1 million direct jobs, which pay an average of $29 per hour.[5] Moreover, each U.S. auto manufacturing job creates nearly 10.5 other positions in industries across the economy.[6] In 2022, U.S. entities invested $48.4 billion in automotive research and development (R&D), which represented about 39 percent of global automotive R&D investment.[7] The industry supports an entire ecosystem of U.S. manufacturers, from steelmaking to semiconductor fabrication.[8] For instance, the industry represents the core of U.S. metal working and related production capabilities, which also entail very important dual-use applications (e.g., the key roles Ford and GM played in building tanks, vehicles, and aircraft during World War II).[9] In short, the U.S. automotive industry is simply too big to fail if America is to have a robust manufacturing sector and vibrant advanced-technology economy that ultimately helps support U.S. defense capabilities.

The administration should not allow Chinese EV makers to construct manufacturing plants in America, especially when doing so would reward both Chinese mercantilist policies and Chinese EV firms’ gambit to circumvent the tariffs the United States has already sensibly imposed on them.

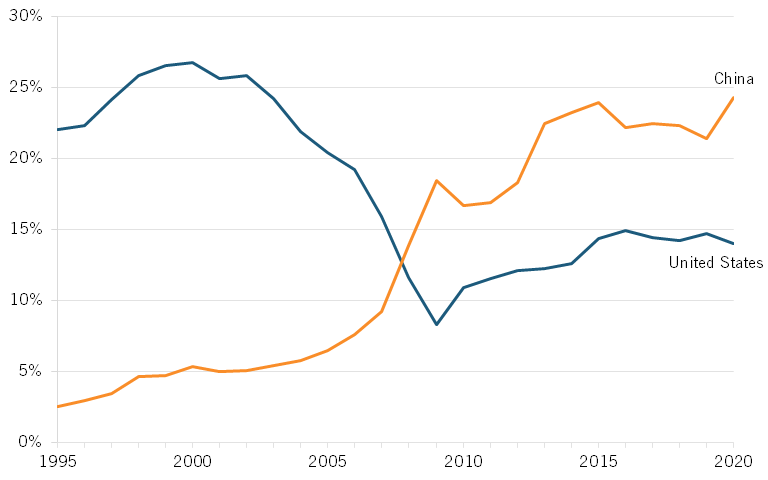

Unfortunately, even before the emergence of the China EV threat, the U.S. auto industry had been struggling. Since 2020, employment has declined by 22.1 percent.[10] That echoes a longer-term trend in which the U.S. economy has become increasingly less specialized in motor vehicles than the global average. This is best illustrated with an analytical statistic known as a “location quotient” (LQ), which measures any region’s level of industrial concentration relative to a larger geographic unit—in this case, a nation relative to the rest of the world. (It is a ratio, so the average LQ in any given industry will be 1.) As of 2020, the U.S. LQ in the motor vehicles industry stood at 0.57, meaning just 57 percent of the relative global average level of production, whereas China’s LQ stood at 1.41, or 41 percent above average.[11] Moreover, the U.S. LQ in motor vehicles dropped by 33 percentage points over the previous 25 years while China’s LQ increased by 35 percentage points. In other words, the U.S. motor vehicles industry has been underperforming and regressing while China’s motor vehicles industry has been over-performing and improving. (See figure 1.) This helps explain why America’s global market share of motor vehicles dropped from 22 percent in 1995 to 14 percent in 2020, while China’s share rose from 2.5 percent to 24 percent. (See figure 2.) As such, U.S. policymaking should focus on bolstering the competitiveness of this sector, not opening the market to subsidized Chinese competitors or permitting those firms to manufacture on U.S. soil.

Figure 1: Industrial performance in motor vehicles (LQ and value-added output, 2020)[12]

Figure 2: U.S. and Chinese global market shares in the motor vehicles industry[13]

It’s certainly true that China has become a serious force in global automotive manufacturing, as the country transformed from manufacturing a mere 5,200 passenger vehicles in 1985 to 26.8 million—21 percent of global production—in 2024.[14] In 2023, China surpassed Japan to become the world’s largest auto exporter. If current global production trends persist, analysts estimate that, by 2030, China will manufacture 36 million vehicles per year, or 4 out of every 10 cars built in the world, as its annual auto exports hit 9 million vehicles, a ninefold increase over China’s 2000 exports of 1 million cars.[15]

With regard to EVs specifically, in 2024, China manufactured about 70 percent of the 17.3 million EVs produced worldwide.[16] In that year, China led the world with 1.25 million EV exports, or 40 percent of the global share.[17] Similarly, China’s battery manufacturing capacity in 2022 stood at 0.9 terawatt hours, roughly 77 percent of the global share.[18] China has also established a near monopoly on EV battery component production, supplying nearly 85 percent of cathode active materials—including for nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) and lithium iron phosphate (LFP) chemistries—and over 90 percent of anode active material production.[19]

To be sure, as ITIF explained in “How Innovative Is China in the Electric Vehicle and Battery Industries?,” Chinese automakers’ burgeoning competitiveness has in part resulted from some degree of genuine innovation.[20] Consider EV battery technology, which matters greatly when the battery accounts for approximately 40 percent of an EV’s cost.[21] As Zeyi Yang wrote in MIT Technology Review, “Just a few years ago, LFP batteries were considered an obsolete technology that would never rival NMC batteries in energy density. It was Chinese companies, particularly CATL, that changed this consensus through advanced research.”[22] As Max Reid, a senior research analyst for EVs and batteries at research firm Wood Mackenzie, explained, “That’s purely down to the innovation within Chinese cell makers. And that has brought Chinese EV battery [companies] to the front line, the tier one companies.”[23]

China’s BYD is now developing “flash charging” technology, a charging/battery system the company claims “can add two kilometers of range per second, or 400 kilometers in five minutes,” which would be three times faster than Tesla’s supercharger (and on average faster than charging a mobile phone).[24]

Chinese EV makers have also innovated regarding many aspects of EV production itself. One commentator wrote about BYD that “it’s blend of vertical integration, cutting-edge automation, and global supply chain mastery has redefined the EV landscape.”[25]

As Paul Gong, UBS head of China auto research, explained, “New EVs are more like computers with batteries on wheels. Chinese carmakers are now ahead of almost everyone else along the entire EV supply chain.”[26] As the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip wrote, “Chinese EVs feature at least two, often three, display screens, one suitable for watching movies from the back seat, multiple lidars (laser-based sensors) for driver assistance, and even a microphone for karaoke.”[27] Beyond the “digital bling,” Chinese automakers such as BYD, Xiaomi, and XPeng have made strides in vehicle automation technology, with one study from the China Society of Automotive Engineers suggesting that “by 2030, a fifth of new cars sold in China will be fully driverless, and 70% will feature advanced assisted-driving technology.”[28]

From 2009 to 2023 alone, China channeled $230.9 billion in subsidies and other support to its domestic EV sector.

Beyond digitalization and automation features, Chinese EV makers have made strides in product and process automation. Xiaomi has further innovated the die-casting processes Tesla originally pioneered, “building an AI program that used a method known as deep learning to simulate how different materials would behave when placed inside the die-cast machine.”[29] In 2023, XPeng introduced “a new platform architecture for making vehicles” that helped it “shorten the R&D cycle for its future models by 20 percent.”[30] Innovations such as these have enabled Chinese EV makers to radically accelerate their R&D and production timelines. In fact, “Chinese automakers are around 30% quicker in development than legacy manufacturers, largely because they have upended global practices built around decades of making complex combustion-engine cars.”[31] Further, “Chinese EV makers offer models for sale for an average of 1.3 years before they are updated or refreshed, compared with 4.2 years for foreign brands.[32]

The enormous scale and speed China brings to EV manufacturing are one element helping its sector to manufacture EVs at lower costs, as they help Chinese companies spread the costs of developing new technology across more vehicles.[33] Indeed, research firm Bernstein estimates that Chinese EVs can cost half as much to make as do European ones.[34] However, as the following section explains, China’s EV cost competitiveness has been driven substantially by a plethora of market-distorting mercantilist policies—notably, massive industrial subsidization.

China’s aggressive use of a range of mercantilist practices including subsidies, intellectual property (IP) theft, forced technology transfer, and preferences for domestic firms have played a dramatic role in advancing China’s EV competitiveness. China’s mercantilist practices are not consonant with the country’s World Trade Organization commitments.[35] Yet, these non-market practices have conferred tremendous advantages on Chinese EV manufacturers, giving them the foundational wherewithal to enter international markets and price their vehicles lower than other competitors do.

Subsidies

China’s subsidies to its EV sector perhaps exceed those directed toward any other sector. Indeed, researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) have estimated that, from 2009 to 2023 alone, China channeled $230.9 billion in subsidies and other support to its domestic EV sector.[36] Moreover, Chinese EV subsidies have only increased in recent years, with an estimated $120.9 billion in subsidies over just the previous three years of that CSIS study ($30.1 billion in 2021, $45.8 billion in 2022, and $45.3 billion in 2023), compared with a total of $49 billion in subsidies the three years prior, and $60.7 billion in subsidies from 2009 to 2017 (then at a $6.74 billion annual rate).[37] Considering batteries, from 2018 to 2023, the Chinese government extended a total of $1.8 billion in subsidies to CATL alone.

BYD received $2.1 billion in subsidies from the Chinese government in 2022 alone, and those subsidies were equivalent to 3.5 percent of the firm’s revenues for that year.

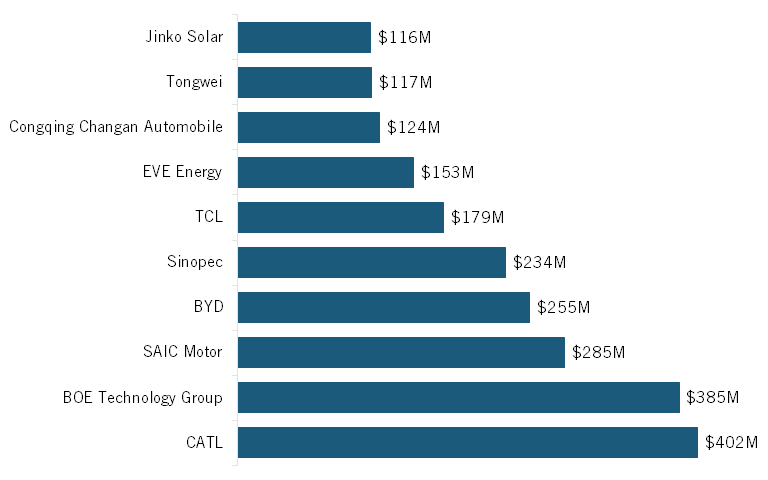

A separate study examined which Chinese companies were the top subsidy recipients among China A-share companies (publicly listed companies in mainland China) and found that half of such firms hailed from China’s auto industry, led by CATL in first place, SAIC Motor in third, and BYD in fourth.[38] (See figure 3.)

Figure 3: Top 10 subsidy recipients among Chinese A-share companies[39]

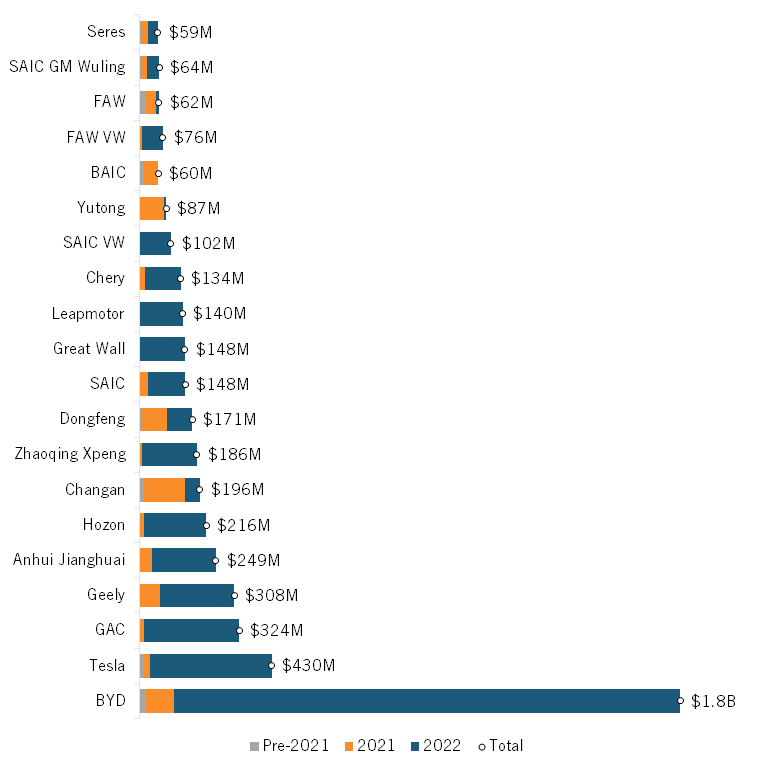

The Kiel Institute for the World Economy found that BYD received $2.1 billion in total subsidies from the Chinese government in the year 2022 alone, and that those subsidies were equivalent to 3.5 percent of the firm’s revenues in that year.[40] Unlike in many countries, a distinctive feature of EV purchase subsidies in China is that they are paid directly to manufacturers rather than to consumers, and are only for EVs produced in China, thereby discriminating against imported vehicles.[41] From 2020 to 2022, BYD led all recipients of EV purchase subsidies in China by nearly fourfold.[42] (See figure 4.)

Figure 4: Top 20 EV purchase subsidy recipients in China[43]

The extensive government subsidies flowing into China’s EV industry have led to considerable global overcapacity. In fact, at one point in 2018, China had over 500 EV start-ups registered, although that number had shrunk to some 200 firms by mid-2024 and to an estimated 130 firms as of August 2025.[44] Nevertheless, significant overcapacity remains, with one assessment finding that Chinese EV overcapacity now stands at between 5 million and 10 million vehicles per year.[45] This overcapacity persists, because, as one analyst explained, “Chinese companies are not responding to demand signals from the market, but production incentives from across all levels of the Chinese government.”[46]

The essential reason why Chinese EV subsidies have been so pernicious to international competition is that they enable Chinese companies to both sustain themselves in industries where they wouldn’t be able to subsist if they had to earn market-based rates of return and, similarly, sell products below cost and sustain losses while still being able to build economies of scale. As the New York Times’ Keith Bradsher explained, China automaker Nio lost $835 million from April through June 2023, equivalent to a loss of $35,000 for each car it sold.[47] (A separate study found that China BYD’s profitability per vehicle in Q3 2023 was just $1,460, compared with $5,330 for Tesla, noting that BYD was underpricing its vehicles to build market scale.)[48] Moreover, if this aggressive strategy of selling vehicles below costs fails, China steps in to rescue the automaker. As Bradsher observed, “When Nio nearly ran out of cash in 2020, a local government immediately injected $1 billion for a 24 percent stake, and a state-controlled bank led a group of other lenders to pump in another $1.6 billion.”[49]

Subsidies allow Chinese companies to both sustain themselves in industries where they wouldn’t be able to subsist if they had to earn market-based rates of return and, similarly, to sell products below cost and sustain losses while still being able to build economies of scale.

Forced Technology Transfer and IP Theft

Forced technology transfer and IP theft represent other key aspects of China’s EV mercantilist playbook. Indeed, the Economist wrote that Chinese EV subsidies “come on top of the ransacking of technology from joint ventures with Western carmakers and South Korean battery-makers.”[50] And while certainly Chinese EV makers have become considerably more capable today, much of that foundation was built off compulsorily transferred Western technology. For instance, when GM sought to sell its early EV, the Volt, in China, “The Chinese government [refused] to let the Volt qualify for subsidies totaling up to $19,300 a car unless G.M. [agreed] to transfer the engineering secrets for one of the Volt’s three main technologies to a joint venture in China with a Chinese automaker.”[51] Similarly, when Ford sought to open a production facility in China, the Chinese government required Ford to open an R&D laboratory employing at least 150 Chinese engineers.[52]

Whatever EV technologies China could not get Western companies to knowingly disclose, the country tried to pilfer by other means. In fact, in 2020, Federal Bureau of Investigation director Christopher Wray warned explicitly that “China is placing a priority on stealing electric car technology,” as the Chinese government is “fighting a generational fight to surpass our country in economic and technological leadership.”[53] As Wray elaborated, “We see Chinese companies stealing American intellectual property to avoid the hard slog of innovation, and then using it to compete against the very American companies they victimized—in effect, cheating twice over.”[54] In February 2020, William Evania, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, singled out two fields where China is putting a priority on technology theft: EVs and aircraft.[55]

U.S. EV companies have felt the brunt of coordinated Chinese efforts to pilfer their technology. In September 2023, Tesla sued Chinese chip designer and auto parts maker Bingling for infringing its IP and stealing its trade secrets, both related to the integrated circuits Tesla uses in its vehicles.[56] In June 2024, Klaus Pflugbell (a Canadian and German national living in China) pleaded guilty to conspiring to sell trade secrets (about EV batteries) that belonged to a leading U.S.-based EV company to Chinese entities.[57]

The Chinese government has long worked to favor domestic over foreign suppliers in automotive supply chains. For instance, China’s “Made in China 2025” strategy (released in 2015) stipulated that more than 70 percent of the one million-plus EVs and plug-in hybrids (then sold annually) in China should be from homegrown brands by 2020. The target set for 2025 was 80 percent of the market (or a then-estimated three million vehicles).[58]

More recently, in March 2024, the Chinese government asked EV makers to sharply increase their purchases from local auto chipmakers, part of a campaign to reduce reliance on Western imports and boost China’s domestic semiconductor industry.[59] China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has directly instructed Chinese automakers to avoid foreign semiconductors if at all possible. The Ministry had previously “set an informal target for automakers to source a fifth [of] their chips locally by 2025.”[60]

While certainly Chinese EV makers have become considerably more capable today, much of that foundation was built off compulsorily transferred Western technology.

Foreign automakers certainly account for a considerable share of U.S. automotive manufacturing. In fact, foreign-headquartered automakers—led by those hailing from European countries, South Korea, and Japan—account for about 45 percent of U.S. vehicle production.[61] Toyota is the largest, with an approximately 15 percent production share, followed by Hyundai and Honda, with 11 and 8.5 percent shares, respectively.[62]

Some will argue: what’s the difference if Chinese EV makers are added to that list? The fundamental answer—as this report’s preceding section explains—is that automakers from these other, and largely U.S.-allied, nations have not been the beneficiaries of rampantly mercantilist practices. Now, it’s true that, 40 years ago, Japanese automakers benefitted from special treatment from the Japanese government, notably shielding Japanese markets from foreign competitors so fledgling Japanese automakers could gain a foothold. (Similar complaints have been lodged against South Korea.) But, even then, at least those nations—and companies therefrom—subscribed to capitalist, market-based principles and hailed from rule-of-law economies. In contrast, Chian’s EV industry is fundamentally backed by the heavy hand of the Chinese state, supported with subsidies and other benefits orders of magnitude greater than what Japanese or South Korean automakers may have ever enjoyed decades before. Moreover, those companies came so to the U.S. market so that they could compete in it; Chinese EV companies would come with the intent to dominate in the U.S. market and ideally eliminate U.S. competitors, as heavily subsidized Chinese companies have done in a range of other sectors, from solar panels to drones.

As noted, those subsidies have helped Chinese competitors defray R&D and production costs, helping them to rapidly attain economies of scale that now enable them to sell EVs at much lower costs than U.S. (and other foreign) competitors can. In other words, Chinese EVs represent a category of product that has systemically benefited from unfair trade practices to the detriment of U.S. competitors. This is why ITIF has called for reform of U.S. trade laws (such as Section 337) so they can be used more vigorously to prevent the import of products from firms in nonmarket, non-rule-of-law economies such as China’s that systemically benefit from unfair government policies and practices.[63]

Not only should the U.S. government be precluding the import of such companies’ products into the country (as of August 2025, America imposed 50 percent tariffs on Chinese automobiles and automotive parts under Section 232 trade authorization), it shouldn’t be permitting such companies to manufacture their products here in the first place.[64] Moreover, to allow BYD or other Chinese EV manufacturers to produce in the United States would provide a precedent and a template for other Chinese companies to circumvent the tariffs America has applied on them. At an October 2024 campaign rally in Greensboro, North Carolina, then-candidate Trump extolled, “Because of me, I just stopped the largest plant anywhere in the world [a proposed Mexican BYD factory] being built in Mexico owned by China.”[65] It certainly made sense to not allow BYD to use Mexico as a backdoor to produce and import EVs into the United States, why would the Trump administration now allow BYD to come in through the front door?

Indeed, in considering whether to allow Chinese EVs into the U.S. market—whether they’re manufactured in America or imported into the U.S. market—policymakers should consider the effect other massively subsidized Chinese industries have had on U.S. high-tech sectors.[66] As George and Usha Haley documented in their book, Subsidies to Chinese Industry: State Capitalism, Business Strategy, and Trade Policy, China’s game plan has long been to “aggressively subsidize targeted industries to dominate global markets.”[67] Consider solar panels. China’s share of global solar panel exports grew from just 5 percent in the mid-2000s to 67 percent by 2018, with Chinese solar output turbocharged by at least $42 billion in subsidies from 2010 to 2012 alone.[68] This instigated a global glut that saw world prices for solar panels crash by 80 percent from 2008 to 2013, bankrupting some 500 of the often much more-innovative foreign competitors in the sector.[69] China has used the same playbook—massively subsidize domestic competitors in an attempt to gain global market share and knock out foreign competitors—in many industries, from steel and aluminum to drones and legacy semiconductors. Why would America now reward that strategy by inviting a Chinese EV producer to manufacture in the U.S. market?

It certainly made sense to not allow BYD to use Mexico as a backdoor to produce and import EVs into the United States. Why would the Trump administration now allow BYD to come in through the front door?

Another key point is that even if BYD or another Chinese automaker were to open a new factory in America, it wouldn’t create any net new manufacturing jobs. Rather, to the extent that a China-owned plant produced vehicles that supplanted vehicle sales that would have been produced by workers at another U.S. plant, it would simply shift U.S. manufacturing workers into the hands of a Chinese-headquartered auto manufacturer. Moreover, to the extent such a factory represented greenfield investment, it would likely get located in a right-to-work state, further accelerating the shift of U.S. auto manufacturing jobs out of the industrial Midwest. Consider that of the top 10 U.S. states that have received EV sector investments thus far—(listed alphabetically) Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee—60 percent, or $75.8 billion of the $158.5 billion investment, has gone to states located south of the Ohio river.[70] Georgia has been the leading recipient of that investment, attracting $31.2 billion, and although Michigan ranks second with $20.4 billion, North Carolina ($19.2 billion), Tennessee ($17.5 billion), Kentucky ($13.7 billion), and South Carolina ($13.6 billion) follow.[71]

Furthermore, allowing Chinese EV makers to manufacture in America wouldn’t palpably change U.S. trade balances with China. In fact, if anything, to the extent Chinese EV manufacturers primarily use parts and components produced by vendors within their existing (China-centered) supply chain, then it would only exacerbate the U.S. trade deficit with China as those parts and components were imported into America. Indeed, it’s likely that there would be far less U.S.-contributed content to such a vehicle. One study finds that 40 percent of the inputs to finished manufactured goods in Mexico come from the United States, whereas for China, that figure is a mere 4 percent.[72] The analogy isn’t perfect, but the statistic illustrates that the number of U.S.-produced parts and components would likely be much lower in a vehicle produced in America by a Chinese-headquartered firm than one by a U.S.-headquartered firm (or one from an allied nation that’s been long operating in the U.S. market).

It should also be noted that the U.S. government has already raised serious concerns about cybersecurity and software issues pertinent to Chinese-manufactured connected vehicles (CVs). On March 17, 2025, new U.S. regulations introduced sweeping restrictions on the importation and sale of CVs and related components with ties to China and Russia.[73] Promulgated by the Bureau of Industry and Security, the Connected Vehicles Rule (“CV Rule”) prohibits the import or sale of CVs and vehicle connectivity system hardware and automated driving systems with a defined nexus from, significant connection to, or association with China.[74] While a slightly separate issue (not all Chinese EVs are CVs—though most will be ultimately), it’s one more reason why the administration shouldn’t permit the manufacture of vehicles by Chinese-headquartered firms in America in the first place.

Europe’s experience with welcoming Chinese EV makers into its market—for production and to sell—should also be instructive. Registrations of Chinese vehicles in Europe have surged 91 percent since the start of 2025 (through end July).[75] Chinese automakers now command roughly as much share of the European auto market as Mercedes-Benz does.[76] In 2023, 40 percent of Chinese EV exports were destined for Europe.[77] And, from 2021 to 2023, Chinese EV shipments to the European Union increased by 361 percent.[78] This has led European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen to complain that Chinese EVs are “flooding the European market” due to “China’s market distortions.”[79] By 2027, analysts predict that BYD will be manufacturing over 700,000 EVs in Europe annually, with some 500,000 coming from a Hungarian plant and 220,000 from one in Turkey.[80] In fact, by 2028, BYD expects that it will manufacture in Europe all the vehicles it sells there, enabling the company to fully circumvent EU tariffs on its EVs, thus obviating the effects (for BYD at least) of the EU’s EV tariffs and hastening the company’s penetration of the European vehicle market.[81] Europe is already experiencing the deleterious consequences of letting BYD through the door; America certainly shouldn’t put itself in the same position.

Lastly, some have argued that the exigency of dealing with global climate challenges means the United States must prioritize those challenges over all else, even if it means welcoming Chinese companies or products into U.S. markets. But that argument is misguided on several fronts. First, just because EVs might be a climate priority doesn’t justify permitting a Chinese EV manufacturer to open a production floor in the United States; if EVs are needed, they should come from American manufacturers or those from manufacturers headquartered in other nations not benefitting from the excessive mercantilist practices. Moreover, research finds that Chinese-manufactured EVs aren’t particularly clean. For instance, climate group T&E has found that the carbon intensity of EV batteries produced in Europe are 37 percent lower than those produced in China.[82] Moreover, research from scholars such as Carnegie Mellon’s Erica Fuchs shows that when buyers prioritize heavily subsidized (and therefore cheaper) technologies—such as Chinese solar photovoltaic panels or EVs—then societies can get locked into a lower level of less-innovative and less-technologically sophisticated products.[83] The need to address climate challenges isn’t a compelling reason to allow Chinese automakers to manufacture in America.

Chinese EVs represent a category of product that has systemically benefited from unfair mercantilist trade practices to the detriment of U.S. and other foreign competitors.

The competitive threat from Chinese EV makers is very real, and America needs a coordinated response, starting with not allowing Chinese EV makers to manufacture their products here. Second, America needs to, with alacrity, articulate a comprehensive and well-conceived national auto sector competitiveness strategy, which could perhaps be modeled along the lines of strategies recently developed for the U.S. biotechnology industry.[84] Such a strategy needs to recognize that Chinese competitors have made some significant leaps in EV and EV battery technologies, and the United States needs to respond in kind. ITIF will be developing such a strategy for release later this year.

Chinese EVs represent the most significant threat the U.S. auto industry has faced in at least the past quarter-century. Chinese EV players compete on nonmarket terms, and are the beneficiaries of massive industrial subsidization and other mercantilist practices that have contributed substantially to their ability to sell vehicles at prices well below those of foreign competitors. The United States has seen the effect of China’s mercantilist playbook before: extensive Chinese industrial subsidies leading to overcapacity that drives global pricing down and eliminates competitors from rule-of-law nations that have to earn market-based rates of return. America must not allow China to effectively use this strategy in automobiles, and a core component of that is precluding Chinese EV makers from manufacturing their vehicles in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Robert Atkinson for his assistance with this report.

About the Author

Stephen Ezell is vice president for global innovation policy at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) and director of ITIF’s Center for Life Sciences Innovation. He also leads the Global Trade and Innovation Policy Alliance. His areas of expertise include science and technology policy, international competitiveness, trade, and manufacturing.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

[5]. AAM, “On a Collision Course,” 2.

[8]. AAM, “On a Collision Course,” 2.

[9]. A. J. Baine, The Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War (Boston, Massachusetts: Mariner Books, 2015).

[14]. Yueyuan Selina Xue, Wei Wei, and Mark J. Greeven, “China’s automotive odyssey: From joint ventures to global EV dominance,” Innovation, January 26, 2024, https://www.imd.org/ibyimd/innovation/chinas-automotive-odyssey-from-joint-ventures-to-global-ev-dominance/; Tim Levin, “Chinese Brands Will Sell A Third Of The World’s Cars By 2030: Study,” InsideEVs, June 30, 2024, https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/chinese-brands-will-sell-a-third-of-the-world-s-cars-by-2030-study/ar-BB1p9P6U?item=flightsprg-tipsubsc-v1a.

[19]. IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” 85.

[25]. Dixit, “How China’s BYD surpassed Tesla with production and battery tech.”

[38]. AAM, “On a Collision Course,” 5.

[44]. “400 Chinese EV companies ceased operations between 2018 – 2025, only a few will dominate towards 2030,” EVBoosters, April 29, 2025, https://evboosters.com/ev-charging-news/400-chinese-ev-companies-ceased-operations-between-2018-2025-only-a-few-will-dominate-towards-2030/; “Only 15 electric vehicle brands in China will be financially viable by 2030, AlixPartners says,” Reuters, July 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/only-15-electric-vehicle-brands-china-will-survive-by-2030-alixpartners-says-2025-07-03/.

[45]. AAM, “On a Collision Course,” 6.

[52]. Robert D. Atkinson and Stephen Ezell, Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2011).

[58]. Xiaoying, “The ‘new three’: How China came to lead solar cell, lithium battery and EV manufacturing.”

[67]. Usha C. V. Haley and George T. Haley, Subsidies to Chinese Industry: State Capitalism, Business Strategy, and Trade Policy (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[77]. Patey, “The Great EV Glut.”

[79]. Patey, “The Great EV Glut.”

[81]. Nick Carey and Christina Amann, “China’s BYD to produce all EVs for Europe locally by 2028, executive says,” Reuters, September 8, 2025, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/chinas-byd-produce-evs-europe-142623542.html.

[83]. Point extrapolated from insights in: Erica Fuchs and Randolph Kirchain, “Design for Location? The Impact of Manufacturing Offshore on Technology Competitiveness in the Optoelectronics Industry” Management Science Vol. 56, No. 12, (December 2010): 2323–2349, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1545027.