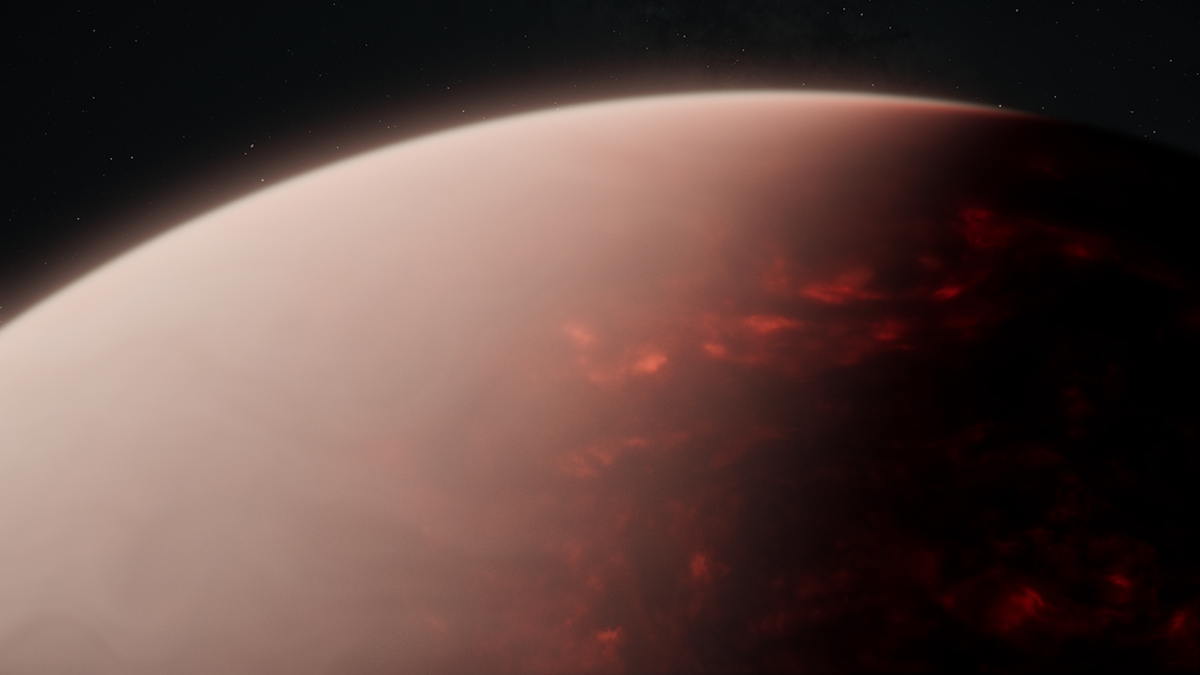

The universe never fails to surprise. Take TOI-561 b, an Earth-sized exoplanet that circles its star on an orbit more than 30 times smaller than Mercury’s.

Despite being blasted by radiation to the point that its rocky surface is…

The universe never fails to surprise. Take TOI-561 b, an Earth-sized exoplanet that circles its star on an orbit more than 30 times smaller than Mercury’s.

Despite being blasted by radiation to the point that its rocky surface is…