In the hushed concert halls of 18th-century London, few could have imagined that the notes floating through the air would become the subject of one of history’s most consequential legal battles. Yet it was during this period that the concept of the “musical work” as legal property was first brought before the courts.

The relationship between music and copyright law reveals profound shifts in the ways we understand creativity, authorship and the nature of musical expression. From the quill-penned musical scores of past centuries to today’s algorithmically generated compositions, the question of who owns a musical creation – and, indeed, what constitutes such a creation – continues to reverberate through our legal frameworks and philosophical understanding.

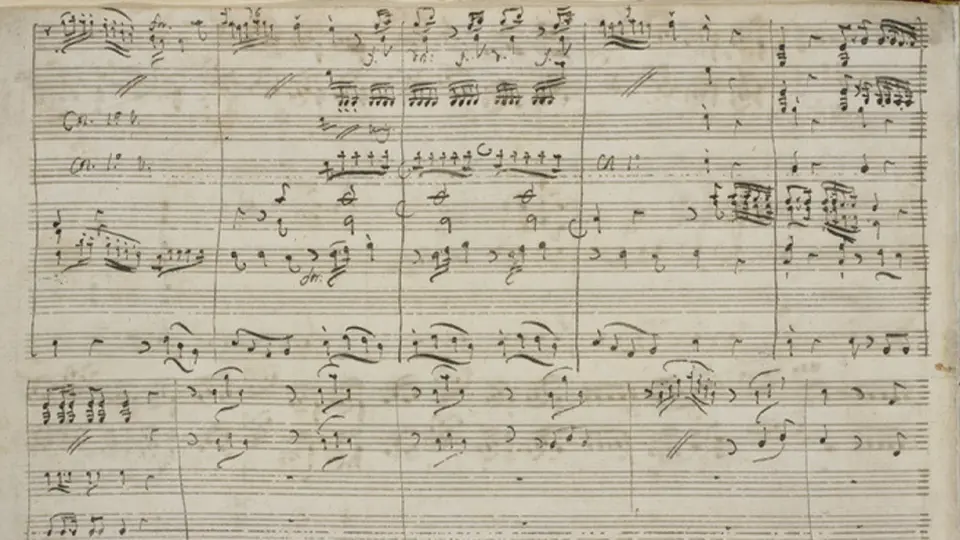

The birth of the musical work

The youngest son of the legendary Johann Sebastian Bach is perhaps an unlikely protagonist in the story of music copyright law.

In 1763, Johann Christian Bach received a royal privilege giving him exclusive publishing rights to his compositions for 14 years. Initially acting as his own publisher, Bach released his trios “Op. 2” and symphonies “Op. 3” under his own label before turning his attention to other ventures, most notably the concert series he directed with his friend Carl Friedrich Abel at London’s Vauxhall Gardens.

Success, however, often breeds imitation. In 1773, Bach discovered that publishers Longman and Lukey had obtained copies of his musical works and were selling them without permission, reaping substantial profits from his creative labor.

Unlike many composers of his time who might have accepted this common practice, Bach possessed both the financial means and determination to challenge it through legal channels.

Through his attorney, Charles Robinson, Bach filed a formal complaint, stating that he “composed and wrote a certain musical composition for the harpsichord called a ‘sonata’” and that “being desirous of publishing the said musical work or composition” he had applied for and been granted a “royal privilege.”

The document described how the publishers had “by undue means obtained copies” and “without your orators license and consent printed, published and sold for a very large profit, divers copies” of his work.

What followed was a four-year legal odyssey that would reshape copyright law. Bach and his collaborator, Abel, initially filed two bills of complaint through a lawyer, but were unsuccessful.

With these words, the “musical work” was legally born

Realizing that his royal privilege offered insufficient protection because its status would erode over time, Bach shifted his strategy and sought clarification that musical compositions were within the scope of the Statute of Anne.

The case finally reached the King’s Bench in 1777, where it was heard by Lord Mansfield, a judge known for his progressive interpretation of copyright law. His ruling was nothing short of revolutionary:

“The words of the Act of Parliament are very large: ‘books and other writings.’ It is not confined to language or letters. Music is a science: it may be written; and the mode of conveying the ideas is by signs and marks. […] We are of the opinion that a musical composition is a writing within the Statute of the 8th of Queen Anne.” (Bach v. Longman, 98 Eng. Rep. 1274 (K.B. 1777)) (Eng.).

With these words, the “musical work” was legally born. Lord Mansfield certified that music was protected by the copyright act, dispelling previous doubt on the matter and ensuring that Bach would be remembered not only for his compositions but also for changing how the law views the art of music.

The significance of Bach v. Longman cannot be overstated. It remained a leading case for more than 60 years and established a precedent for wide interpretation of copyright law that extended to anything regarded as a book or form of writing.

It preceded the British Copyright Act of 1842, which was another significant victory for composers, extending the duration of copyright ownership from 14 to 42 years and including exclusive public performance and publishing rights to musical compositions.

The Berne Convention of 1886 advanced these protections at an international level. While it does not prescribe what qualifies as a work or not, it defines protected works as “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression.”

Among the Berne Convention’s list of protected works are “dramatic-musical works” and “musical compositions with or without words.” These concepts still apply to operas, musicals and all kinds of musical works today.

Evolving definitions

Musical works still occupy a unique nature. “More so than any other artistic endeavors, music possesses ethereal qualities that infiltrates and permeate[s] multiple facets of our existence in a complex manner,” writes J. Michael Keyes in his 2004 essay “Musical Musings: The Case for Rethinking Music Copyright Protection.”

The complexity has led to divergent approaches across jurisdictions. In the UK, the Imperial Copyright Act 1911 implemented the standard set up by the Berne Convention but did not define the term “musical work.” The Copyright Act 1956 maintained this silence.

Only in 1988, with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, did British law articulate that a musical work consisted of “music, exclusive of any words or action intended to be sung, spoken or performed with the music.”

The US followed a similar pattern of gradual recognition. The first Copyright Act of 1790 did not mention musical compositions, referring only to “maps, charts and books.” US law during this period focused primarily on knowledge rather than creativity and art. It wasn’t until 1831 that melody and text received legal protection and, even then, the law remained silent on the creative process underlying musical works.

Subsequently, as David Suisman notes in his 2009 book “Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music,” the Copyright Act of 1909 “fixed the course of American music copyright law for most of the 20th century. But although the law named piano rolls and phonograph records as ‘copies’ of copyrighted music within the meaning of the law, it did not make the sounds themselves the object of copyright. […] The music of piano rolls and phonograph records was inscribed into law not as sound but as ‘text.’”

When notes became numbers

The ambiguities surrounding musical works have been dramatically amplified by technological change. One of the most significant shifts occurred in the relationship between written notation and sound itself. Since the only way to preserve music historically was through written notation, copyright ownership in musical works developed as a form of intellectual property incorporated into musical texts – namely, scores.

However, the 1971 amendment to the US Copyright Act extended protection to recorded sound itself. This distinction is also made in the Rome Convention and other civil law jurisdictions that treat producers of sound recordings as holders of related rights. Records receive copyright protection as independent works, in addition to the protection accorded to the musical work embodied within them. This is the only field of art protected by copyright law for which a distinction exists between the work and its recorded format.

There is an added layer of complexity in the modern era: when new rights were enacted to protect recordings in the 20th century, phonographic rights were invested in the record company or agent who commissioned the recording. A new commodity form, the master recording, was enshrined, yet there was still no question of recognizing the creator.

When an algorithm generates a new composition, who owns the copyright to this work?

Today, as digital recording and distribution technologies have democratized music production, the discussion about whether a work generated by AI is copyrightable or can be the object of related rights is unfolding.

Digital technologies have brought together what were once separate tools – instruments, recording machines and computers – fundamentally altering both the creative process and the way we conceptualize ownership within it.

The digital age has given rise to entirely new forms of musical creativity expressed through concepts radically different from earlier periods.

AI-generated music and copyright

As we look to the future, the emergence of artificial intelligence in music composition presents perhaps the most profound challenge yet to our conception of musical authorship and copyright.

When an algorithm trained on thousands of human-created works generates a new composition that sounds indistinguishable from one created by a human composer, who, if anyone, owns the copyright to this work?

The question echoes the fundamental issues raised in Bach v. Longman but with new dimensions that the 18th-century courts could never have imagined.

Just as Lord Mansfield had to determine whether musical notation could be considered a “writing” under the Statute of Anne, today’s courts must grapple with whether AI-generated music constitutes a work of authorship at all.

This challenge is all the more complex because AI systems disrupt traditional notions of creativity. While humans design the algorithms and provide training data, the AI itself generates new music with increasing autonomy.

This raises profound questions about whether traditional copyright frameworks can accommodate these technological developments or whether entirely new approaches are needed.

The unfinished symphony

The journey from Bach’s landmark case to today’s digital and AI challenges reveals a consistent pattern: copyright law must perpetually keep pace with technological change and evolving conceptions of creativity.

The history of music copyright is, in many ways, a history of attempts to define the indefinable – to capture in legal language the elusive essence of musical creativity.

From Lord Mansfield’s ruling that music “may be written; and the mode of conveying the ideas is by signs and marks” and the Berne Convention incorporating musical works, however openly defined, to modern laws that separate composition from sound recording, each legal framework reflects the technological realities and philosophical assumptions of its time.

The challenge for copyright law is to keep fulfilling copyright’s fundamental purpose

As we stand at the threshold of the AI revolution in music creation, perhaps the most valuable lesson from this history is not any particular legal doctrine but rather the recognition that our conceptions of musical works and authorship are not fixed but evolving.

Imagine what would have happened had Berne negotiators decided to define the term in 1886. The “musical work” as a legal concept was born from Johann Christian Bach’s determination to assert his creative rights – and it continues to transform with each new technological development and artistic innovation.

The challenge for copyright law in the 21st century is to keep fulfilling copyright’s fundamental purpose: to recognize and reward human creativity in all its forms. This will require not just legal ingenuity but also a willingness to reconsider our most basic assumptions about what music is and how it comes into being.

Bach’s legacy, then, is not just the precedent that he established but the ongoing conversation he initiated – an unfinished symphony of legal thought that continues to evolve with each new technological revolution and artistic movement.

As we face the challenges of AI and whatever technologies may follow, we would do well to remember that the questions we ask today about ownership and creativity echo those first raised in a London courtroom almost 250 years ago by a composer determined to claim what he believed was rightfully his.

About the author

Eyal Brook heads the artificial intelligence practice at S. Horowitz & Co and has written extensively on musical authorship in the age of AI. Eyal is a senior research fellow at the Shamgar Center for Digital Law and Innovation at Tel Aviv University and an adjunct professor, teaching courses including law, music and artificial intelligence at Reichman University and the Ono Academic College.

Disclaimer: WIPO Magazine is intended to help broaden public understanding of intellectual property and of WIPO’s work and is not an official document of WIPO. Views expressed here are those of the author, and do not reflect the views of WIPO or its Member States.