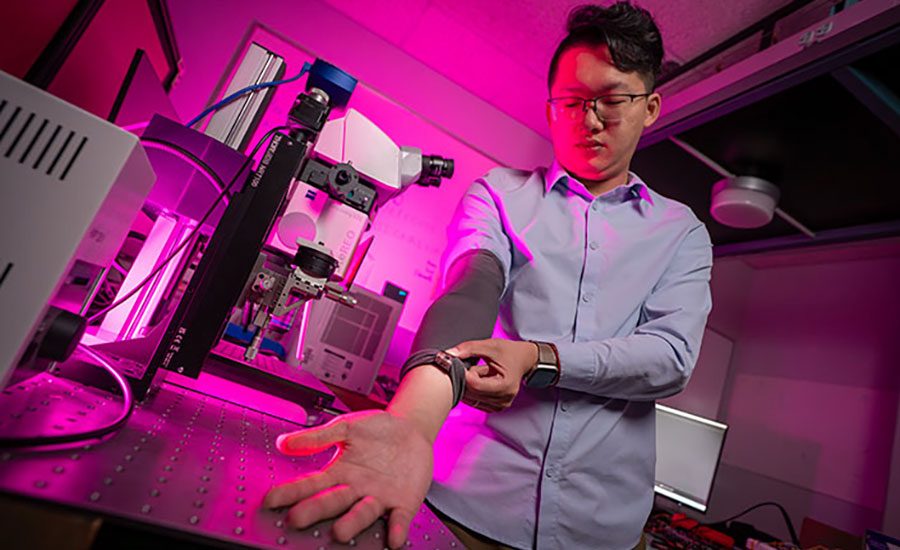

SAN DIEGO—Engineers at the University of California San Diego have developed a next-generation wearable device that enables people to control robots and other machines using everyday gestures. It combines stretchable electronics with artificial…

SAN DIEGO—Engineers at the University of California San Diego have developed a next-generation wearable device that enables people to control robots and other machines using everyday gestures. It combines stretchable electronics with artificial…