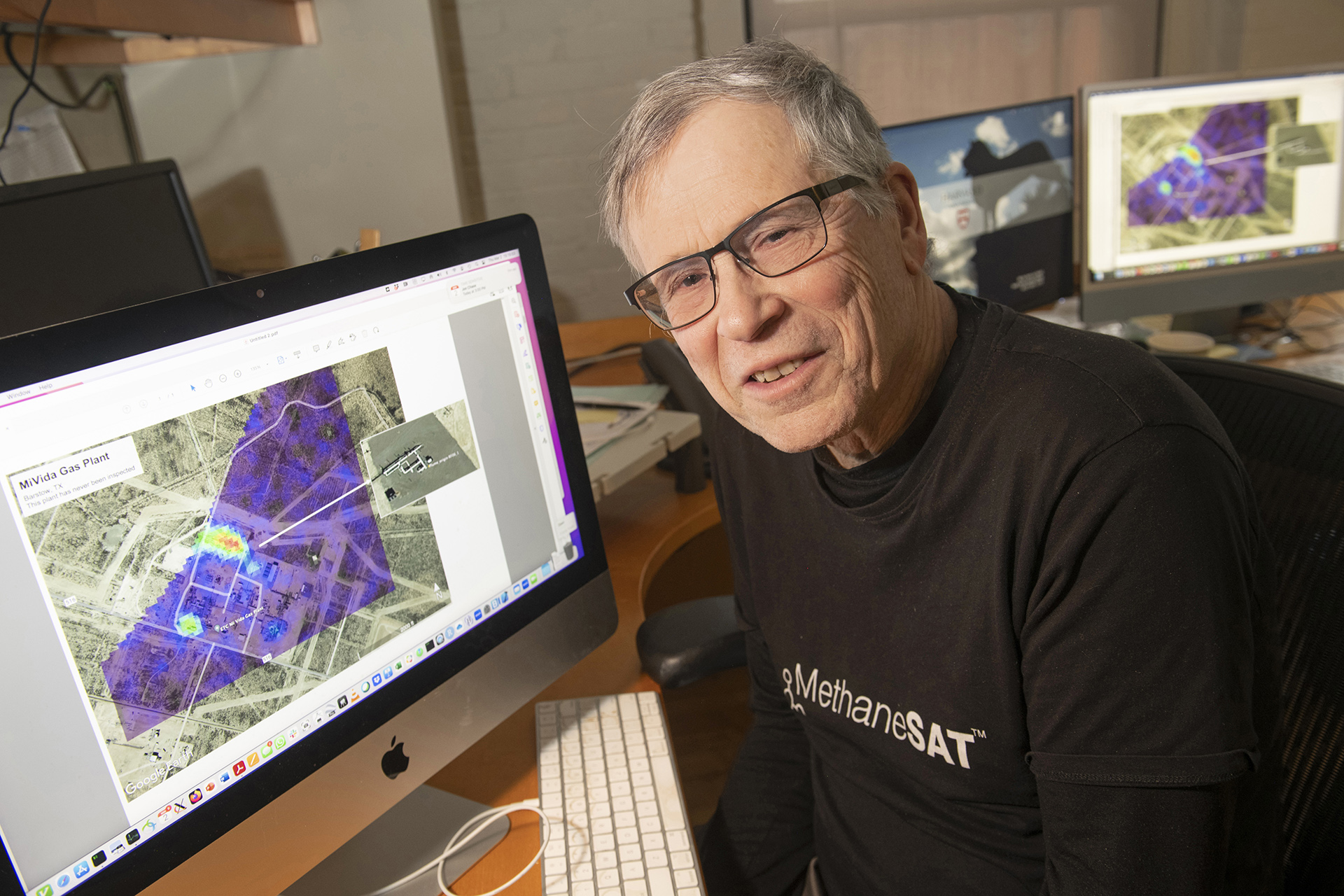

On June 20, the Environmental Defense Fund announced that its MethaneSAT satellite had lost contact with Earth and is presumed lost. MethaneSAT, which its builders say is the most advanced methane-imaging satellite ever put in orbit, sought to globally map, then track emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide. Their aim is to spur action to plug leaks, initially from the oil and gas industry, as a way to significantly lower near-term warming of the atmosphere. The satellite’s main instrument, a highly sensitive spectrometer that can detect methane sources from space with unparalleled precision, was designed by a team led by Harvard scientists. In this edited conversation, the Gazette spoke with the project’s principal investigator, Steven Wofsy, the Abbott Lawrence Rotch Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science, about the loss, the data already gathered, and possible steps ahead.

When did you hear that they were having problems with the satellite?

We monitor the satellite Operations Slack channel and that Friday, June 20, there was a note that it had failed to make a contact. That’s not so unusual, because a cosmic ray event or a solar storm can cause a glitch. The satellite is supposed to reboot and go into safe mode: It takes in light on its solar panel and waits for instruction. It didn’t do that this time — we found that out on Saturday. Then there’s a watchdog that’s supposed to “bark” — it reboots the whole system — if it hasn’t received any communications within 24 hours. The watchdog didn’t bark. Then a second watchdog didn’t bark on Monday morning. That meant that the satellite probably didn’t have power. By the time Monday was over, we had a quite firm indication that the satellite was likely lost.

It’s not common, but this happens to satellites. We still have a year’s worth of data and, at the highest level, MethaneSAT’s mission was and still is to make a quantitative assessment of emissions of methane from the oil and gas industry and understand what the methane intensity is: how much methane is lost for each unit of natural gas that’s sold.

“I’m not planning on throwing in the towel at the moment. We have so much interesting data and so much work to do.”

You’re studying methane because it’s such a potent greenhouse gas?

It’s the second-most-important greenhouse gas and it contributes to air pollution. Methane concentrations have almost tripled since preindustrial times, so the human impact has been huge. MethaneSAT was focused on the oil and gas sector, but agriculture, solid waste, and some other sectors also contribute to human-caused warming. We collected good data over almost 1,000 sites. There’s two distinct modes in which methane is released by the oil and gas industry. One manifests as a point source, so a tank that’s open or a leaking pipe. The second is more dispersed, an area of diffuse emissions. MethaneSAT was designed to be able to quantify both of those, and that has not been done before. Now, we’ve got beautiful results that show you can do that.

The MethaneSAT mission was to do this characterization and then track it over time to see the trend. Hopefully, by providing this information to industry, to governments, to stakeholders, to NGOs we can incentivize reductions of methane emissions. It should be quite clear that methane emissions to the atmosphere from oil and gas serve no constructive purpose. It’s abundant but finite. It’s a wasted resource and has a bad effect on the atmosphere.

What’s the next step?

What we’re planning is to take the data that we have and create the high-impact data products that we promised: satellite-observed concentrations of methane. One of the things that we had to do was develop new methods for relating the excess methane that you see over an oil and gas field to the rate at which it’s being emitted to the atmosphere. That’s been done different ways before but because of the special characteristics of our sensor, we had both a lot more information than people have ever had and also a challenge to use it constructively. That’s something that we have accomplished and we’re going to use it. Around the end of this calendar year, we should be able to provide these high-impact data and analysis products that will tell the world, for each of these oil and gas production areas, how much methane is being emitted, and what the methane intensity is for that area.

“Methane emissions to the atmosphere from oil and gas serve no constructive purpose. It’s abundant but finite. It’s a wasted resource and has a bad effect on the atmosphere.”

How happy were you with the performance of the satellite before it was lost?

Its capability for creating images of methane concentrations at very high spatial resolution, over large areas, at very high precision, exceeded our expectations in every respect. Plus, we’re not finished refining our analysis, so there will be additional improvements. We designed the satellite at Harvard with a lot of help from experts in the field and with a lot of help from Ball Aerospace, now BAE. The type of data that we’ve collected really doesn’t exist from any other satellite.

The mission was to map these places and then look at change over time. Were you able to finish that first part, finding the hotspots?

Yes. We know where the oil and gas provinces are. We didn’t get all of them, but we have a major fraction, and clear enough data that we can characterize their emissions. Obviously, we’re not going to be able to track them over time but there are several different initiatives that we’re putting forward to try to achieve that goal. We have two airborne sensors that perform similarly to MethaneSAT and we’ll be flying those, if we can raise the funds, to track emissions over North America. The second initiative is to use the tools that we’ve developed for data from MethaneSAT on data from other satellite platforms. JAXA [Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency] just launched a satellite called GOSAT-GW [Global Observing SATellite for Greenhouse gases and Water cycle], which could be analyzed in a way that’s similar. At the end of the summer, the Europeans are launching a satellite called Sentinel-5, which will complement their current Sentinel 5p that has the best methane sensor in the world on it, the TROPOMI [TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument] sensor. The methods that we’ve developed can be applied to some of those satellite products. We’re also hoping to get involved in another new satellite, though that’s TBD.

One of the innovations of MethaneSAT was that it was built with private funding, which is unusual for a satellite. Is that model still working, and might it be important for the new satellite being discussed?

The model is holding up right now. Whether or not the funders would be inclined to fund a second one is still to be determined. It’s an expensive thing, and it’s quite clear that government entities — particularly in the United States — are not going to do anything like this. You might also expect that with advancing technology, other methane-sensing satellites would go into orbit that would be able to do the same job. That hasn’t happened and we don’t know of any plans to fly something with the capabilities of MethaneSAT. So we would relish the opportunity to do it. We’ll see what happens, it’s early days yet.

If a new satellite is approved, how long would that take?

It might take 2½ or three years to put one up, if you got going in a hurry. It’s all speculation at this point, but we know how to build it, and the parts are there. I’m not planning on throwing in the towel at the moment. We have so much interesting data and so much work to do.

What was the mood in your lab when those working on the project heard about MethaneSAT’s loss?

People were sad for sure — even me — but everybody recognizes that we have what we need to accomplish the first part of this very ambitious global agenda. We have a lot of work to do over the next months, maybe into next year, and that gives people a focus. So people have their sleeves rolled up. Space is risky, but it still stings when the risk comes and bites you in the butt.

All this has been happening amid the turmoil of federal funding cuts. How have you been juggling those cuts at the same time you’re dealing with the loss of the satellite?

I lost four grants. One was terminated and three were awarded but never transmitted to Harvard. That’s a significant loss — they supported our upper atmosphere research program — but only one of them supported MethaneSAT or MethaneAIR activities. Overall, we’re still able to carry out the fundamental research on methane that we’ve been doing.