A million-year-old human skull suggests that the origins of modern humans may reach back far deeper in time than previously thought and raises the possibility that Homo sapiens first emerged outside of Africa.

Leading scientists reached this conclusion after reanalysis of a skull known as Yunxian 2 discovered in China and previously classified as belonging to a member of the primitive human species Homo erectus.

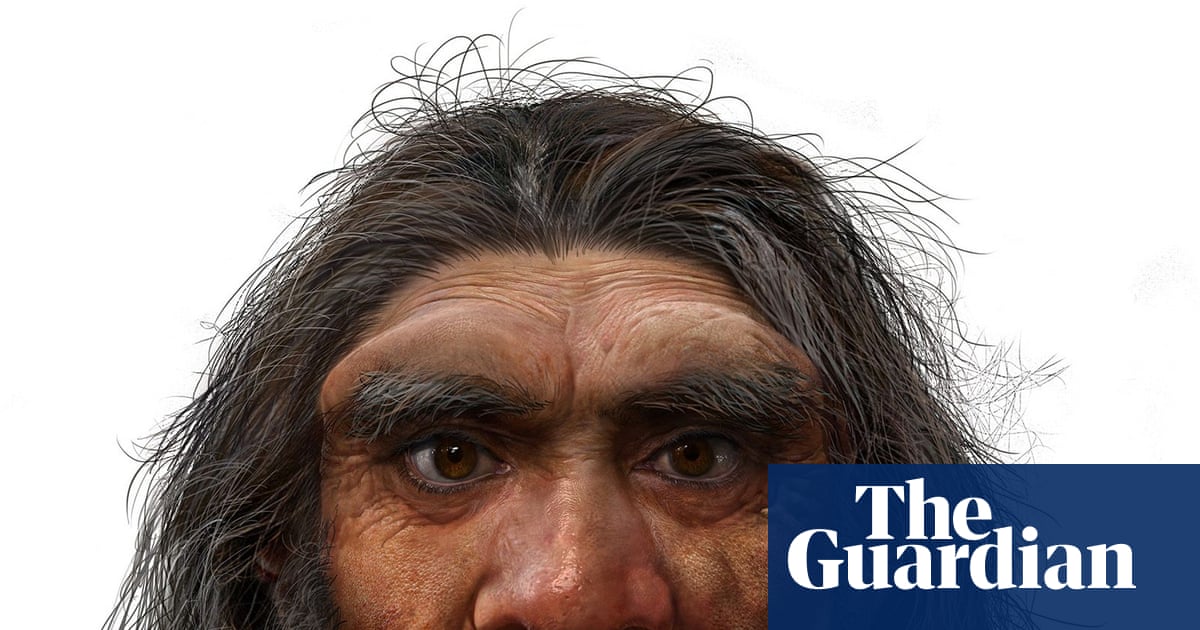

After applying sophisticated reconstruction techniques to the skull, scientists believe that it may instead belong to a group called Homo longi (dragon man), closely linked to the elusive Denisovans who lived alongside our own ancestors.

This repositioning would make the fossil the closest on record to the split between modern humans and our closest relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans, and would radically revise understanding of the last 1m years of human evolution.

Prof Chris Stringer, an anthropologist and research leader in human evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, said: “This changes a lot of thinking because it suggests that by one million years ago our ancestors had already split into distinct groups, pointing to a much earlier and more complex human evolutionary split than previously believed. It more or less doubles the time of origin of Homo sapiens.”

The skull was first unearthed in Hubei province in 1990, badly crushed and difficult to interpret. Based on its age and some broad-brush traits, it was assigned as Homo erectus, a group that is thought to have contained direct ancestors of modern humans.

The latest work used advanced CT imaging, high-resolution surface scanning and sophisticated digital techniques to produce a virtual reconstruction of the skull. The skull’s large, squat brain case and jutting lower jaw are reminiscent of Homo erectus. But the overall shape and size of the brain case and teeth appear to place it much closer to Homo longi, a species that scientists have recently argued should incorporate the Denisovans.

This would push the split between our own ancestors, Neanderthals and Homo longi back by at least 400,000 years and, according to Springer, raises the possibility that our common ancestor – and potentially the first Homo sapiens – lived in western Asia rather than Africa.

“This fossil is the closest we’ve got to the ancestor of all those groups,” Stringer said.

A computational analysis of a wider selection of fossils suggests that in the last 800,000 years, large-brained humans evolved along just five major branches: Asian erectus, heidelbergensis, sapiens, Neanderthals and Homo longi (including the Denisovans).

“We feel that this study is a landmark step towards resolving the ‘muddle in the middle’ [the confusing array of human fossils from between 1 million and 300,000 years ago] that has preoccupied palaeoanthropologists for decades,” Stringer said.

The findings run counter to some recent analyses based on genetic comparisons of living humans and ancient DNA, meaning the conclusions are likely to be contentious.

Dr Frido Welker, an associate professor in human evolution at the University of Copenhagen, who was not involved in the research, said: “It’s exciting to have a digital reconstruction of this important cranium available. If confirmed by additional fossils and genetic evidence, the divergence dating would be surprising indeed. Alternatively, molecular data from the specimen itself could provide insights confirming or disproving the authors’ morphological hypothesis.”

The findings are published in the journal Science.