Cristian Fleming paid around $70,000 for his dream car, a Fisker Ocean. He was drawn to the new EV’s 350-mile range, eco-friendly image, and quirky features like “California Modes,” which rolls down nearly every window at once.

“I’ve always bought my cars because I love the way they look,” Fleming says. “That’s probably my first mistake.”

But his joy soon turned sour. In June 2024, seven months after Fleming’s purchase, Fisker collapsed into bankruptcy, having only delivered 11,000 vehicles.

Early adopters were left with cars plagued by battery failures, glitchy software, inconsistent key fobs, and door handles that did not always open. With the company gone, there was no way to fix any issues. Regulators logged dozens of complaints as replacement parts vanished. Passionate owners who spent top dollar on high-end trims saw their cars reduced to expensive driveway ornaments.

Rather than accept defeat, thousands of Ocean owners have organized into their own makeshift car company. The Fisker Owners Association (FOA) is a nonprofit that’s launched third-party apps, built a global parts supply chain, and came together around a future for their orphaned vehicles. It’s part car club, part tech startup, part survival mission. Fleming now serves as the organization’s president.

”Everyone who has an Ocean loves it,” says Clint Bagley, an early adopter in California’s Bay Area and FOA’s treasurer. “Until the key fob stops working again and you can’t get into it.”

FOA calls itself the first entirely owner-controlled EV fleet in history. So far, 4,055 Ocean owners have signed up, paying $550 a year in dues that the group estimates will raise around $3 million annually, about 0.1 percent of Fisker’s peak valuation. Only verified Ocean owners can become full members, but anyone can donate.

The grassroots effort has precedent — DeLorean diehards and Saab enthusiasts have kept their favorite brands alive after factory closures. But those efforts focused on preserving aging vehicles. FOA is attempting something different: real-time software updates and hardware improvements for a connected, two-year-old EV fleet.

“I’ve been a car nerd my whole life, so to be in the position we are in now – with the ability to have input into the future direction of the car I love driving every day – is a unique experience,” says Andrew Bock, an FOA member.

The organization has spawned three separate companies. Tsunami Automotive handles parts in North America while Tidal Wave covers Europe, scavenging insurance auctions and contracting with tooling manufacturers to reproduce components. UnderCurrent Automotive, run by former Google and Apple engineers, focuses on software solutions.

UnderCurrent’s first product is OceanLink Pro, a third-party mobile app now used by over 1,200 members that restores basic EV features, such as remote battery monitoring and climate control. A companion device called OceanLink Pulse adds wireless CarPlay and Android Auto, with plans for future upgrades including keyless entry.

“Those are things you would have expected to be in a $70,000 luxury car,” Bagley says. “But, you know, we’re happy to provide what the billion-dollar automaker apparently couldn’t.”

Image: Fisker

Auto industry analysts are divided on FOA’s prospects.

“For owners of any EV company that stops production, it makes sense to form an organization to share resources and maintenance ideas,” Seth Goldstein, an EV industry analyst at Morningstar, says. “This is a good way for Fisker owners to be able to maintain and upgrade their vehicles over time.”

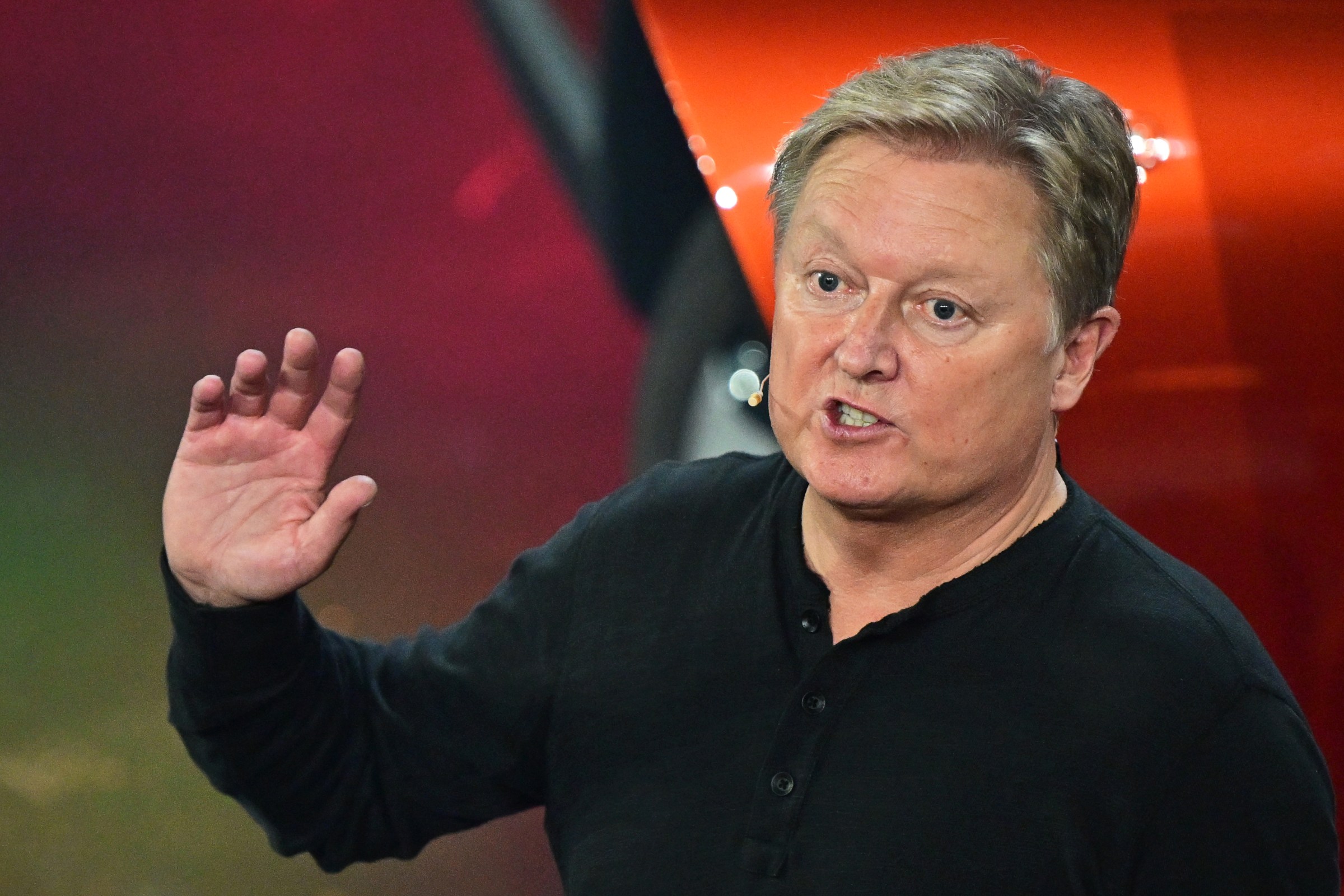

Meanwhile, insiders say Fisker’s executives, including its CEO and founder, Henrik Fisker, failed to keep operations running while making a decent product.

“I think to see particular vehicle’s owner group team together, collaborate, and develop solutions to problems and make updates to their own vehicles without assistance from Fisker itself is wild, but I applaud their efforts,” Robby DeGraff, manager of product and consumer insights at AutoPacific, tells The Verge. “It’s a shame and quite frankly pathetic that Henrik Fisker has vanished into thin air and left the thousands of Ocean owners to fend for themselves.”

‘They’re dangerous’

FOA’s remaining obstacles are severe. Resale values have plunged more than 40 percent since Fisker’s collapse, according to retail specialists CarGurus. Karl Barth, an attorney representing Ocean owners in ongoing litigation, says some clients’ cars have shut down mid-turn while others received trade-in offers as low as $3,000.

“They’re dangerous,” Barth says, citing an August recall for brake software that reduced regenerative braking after hitting bumps. It covered 7,745 vehicles.

But, like FOA, companies also see value in the vehicles. In July, American Lease, a New York taxi company, bought more than 3,200 unsold Oceans for $46 million and now rents them to Uber and Lyft drivers from a Bronx parking lot. FOA initially hoped to partner with American Lease on software updates, but Bagley says the relationship soured over disagreements about handling recalls.

Fisker and American Lease didn’t respond to several requests for comment.

Despite the headwinds, FOA remains optimistic about its unprecedented experiment. Whether a volunteer organization can succeed where a billion-dollar startup failed remains an open question.

For now, the Ocean’s future depends on owners determined to do what Fisker could not: keep their cars running. If FOA doesn’t work, Bagley likens Fisker to the Fyre Festival, but instead of soggy cheese sandwiches and glamping yurts, Ocean buyers got a luxury EV that might stop working at any moment.