Paleontologists have discovered protein sequences within dense enamel tissues of ancient rhinocerotid and proboscidean fossils collected at sites of Buluk and Loperot in the Turkana Basin, Kenya.

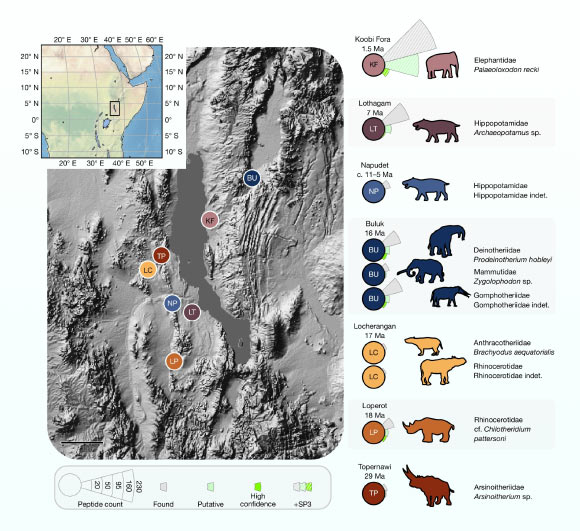

The Turkana Basin within the East African Rift System preserves fossil assemblages that date back more than 66 million years; Green et al. collected powdered samples for paleoproteomic analysis from the dense interiors of enamel from large herbivores from the Early Pleistocene back to the Oligocene (29 million years). Image credit: Green et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09040-9.

“Teeth are rocks in our mouths,” said Dr. Daniel Green, a researcher at Harvard University and Columbia University.

“They’re the hardest structures that any animals make, so you can find a tooth that is a hundred or a hundred million years old, and it will contain a geochemical record of the life of the animal.”

“That includes what the animal ate and drank, as well as its environment.”

“In the past we thought that mature enamel, the hardest part of teeth, should really have very few proteins in it at all.”

However, utilizing a new newer proteomics technique called liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), the authors were able to detect a great diversity of proteins in different biological tissues.

“The technique involves several stages where peptides are separated based on their size or chemistry so that they can be sequentially analyzed at higher resolutions than was possible with previous methods,” said Dr. Kevin Uno, also from Harvard University and Columbia University.

“We and other scholars recently found that there are dozens — if not even hundreds — of different kinds of proteins present inside tooth enamel,” Dr. Green said.

With the realization that many proteins are found in contemporary teeth, the researchers turned to rhinocerotid and proboscidean fossils.

As herbivores, these animals had large teeth for grinding their diet of plants.

“These mammals can have enamel two to three millimeters thick. It was a lot of material to work with,” Dr. Green said.

“What we found — peptide fragments, chains of amino acids, that together form proteins as old as 18 million years — was field-changing.”

“Nobody’s ever found peptide fragments that are this old before.”

Until now, the oldest published materials are about 3.5 million years old.

“The newly discovered peptides cover a range of proteins that perform different functions, altogether known as the proteome,” Dr. Green said.

“One of the reasons that we’re excited about these ancient teeth is that we don’t have the full proteome of all proteins that could have been found inside the bodies of these ancient elephants or rhinoceros, but we do have a group of them.”

“With such a collection, there might be more information available from a group of them than just one protein by itself.”

“This research opens new frontiers in paleobiology, allowing scientists to go beyond bones and morphology to reconstruct the molecular and physiological traits of extinct animals and hominins,” said Dr. Emmanuel Ndiema, a researcher at the National Museum of Kenya.

“We can use these peptide fragments to explore the relationships between ancient animals, similar to how modern DNA in humans is used to identify how people are related to one another.”

“Even if an animal is completely extinct – and we have some animals that we analyze in our study who have no living descendants — you can still, in theory, extract proteins from their teeth and try to place them on a phylogenetic tree,” Dr. Green said.

“Such information might be able to resolve longstanding debates between paleontologists about what other mammalian lineages these animals are related to using molecular evidence.”

The findings appear today in the journal Nature.

_____

D.R. Green et al. Eighteen million years of diverse enamel proteomes from the East African Rift. Nature, published online July 9, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09040-9