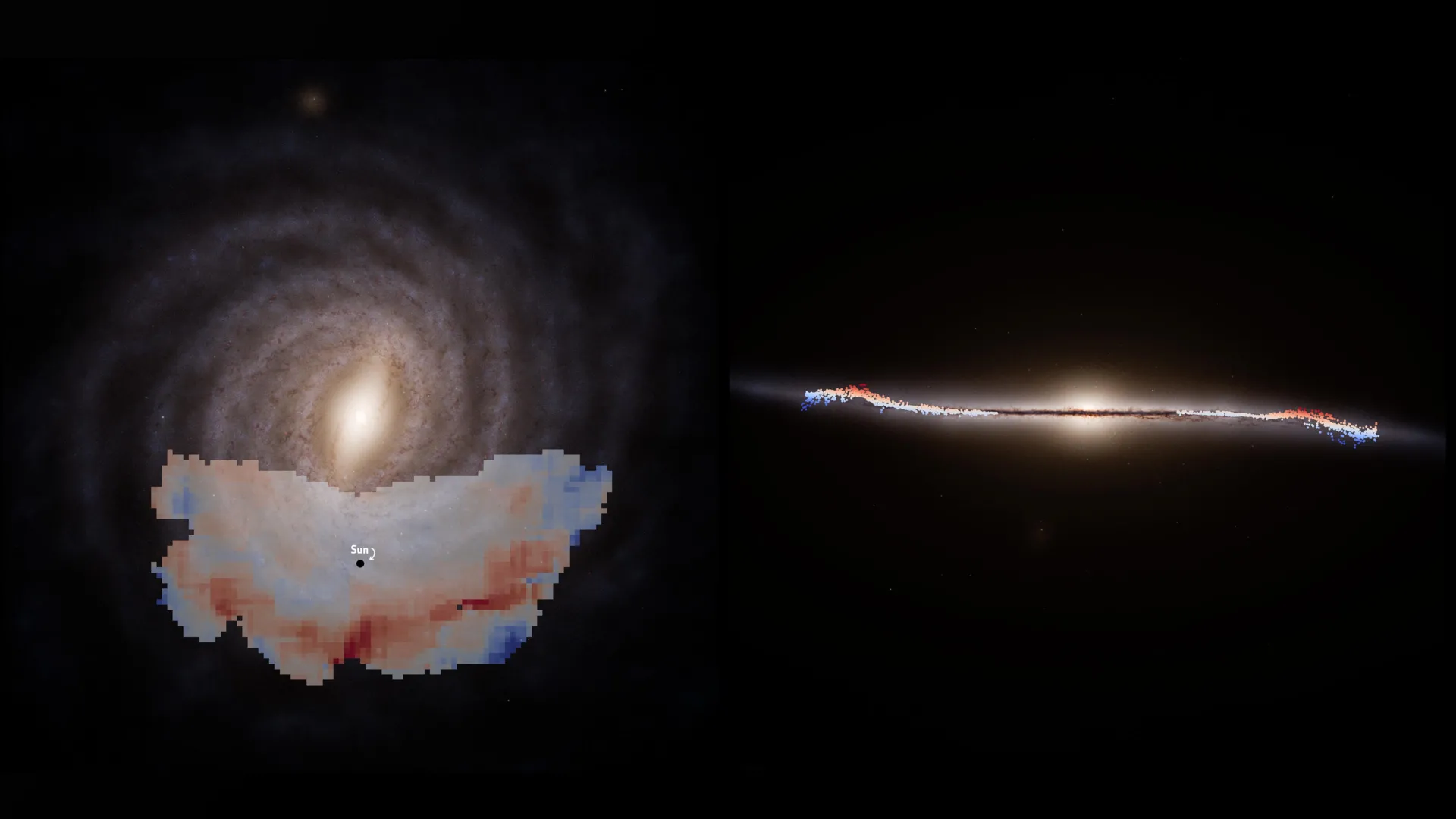

Our Milky Way is constantly in motion: it spins, it tilts, and, as new observations reveal, it ripples. Data collected by the European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope show that our galaxy is not only rotating and wobbling but also sending out…

A giant wave is rippling through the Milky Way, and scientists don’t know why