Data collection

The data for the GENE-SMART study (Genetic Evaluation for breast cancer in the Netherlands: Studying a Mainstreaming Approach for Redefining Testing pathways), a nationwide retrospective cohort study, was obtained from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), kept by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL). Specially trained registrars gathered data about patient, diagnostic, tumour, treatment characteristics and whether genetic testing was performed, directly from patient files in almost all Dutch hospitals (73 of 75 hospitals). Two hospitals were excluded from the study as data from these hospitals was not collected by data registrars employed by IKNL. In the remaining hospitals (n = 73), patients were excluded if they had undergone genetic testing before their breast cancer diagnosis or if data about the hospital of diagnosis, tumour stage or postcode was unknown.

Study sample.

The study included newly diagnosed Dutch breast cancer patients diagnosed between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022. Patients aged 18 or older were eligible for genetic testing if they met the patient characteristics as described in the Dutch guidelines [21].

Variables

Organization of genetic care

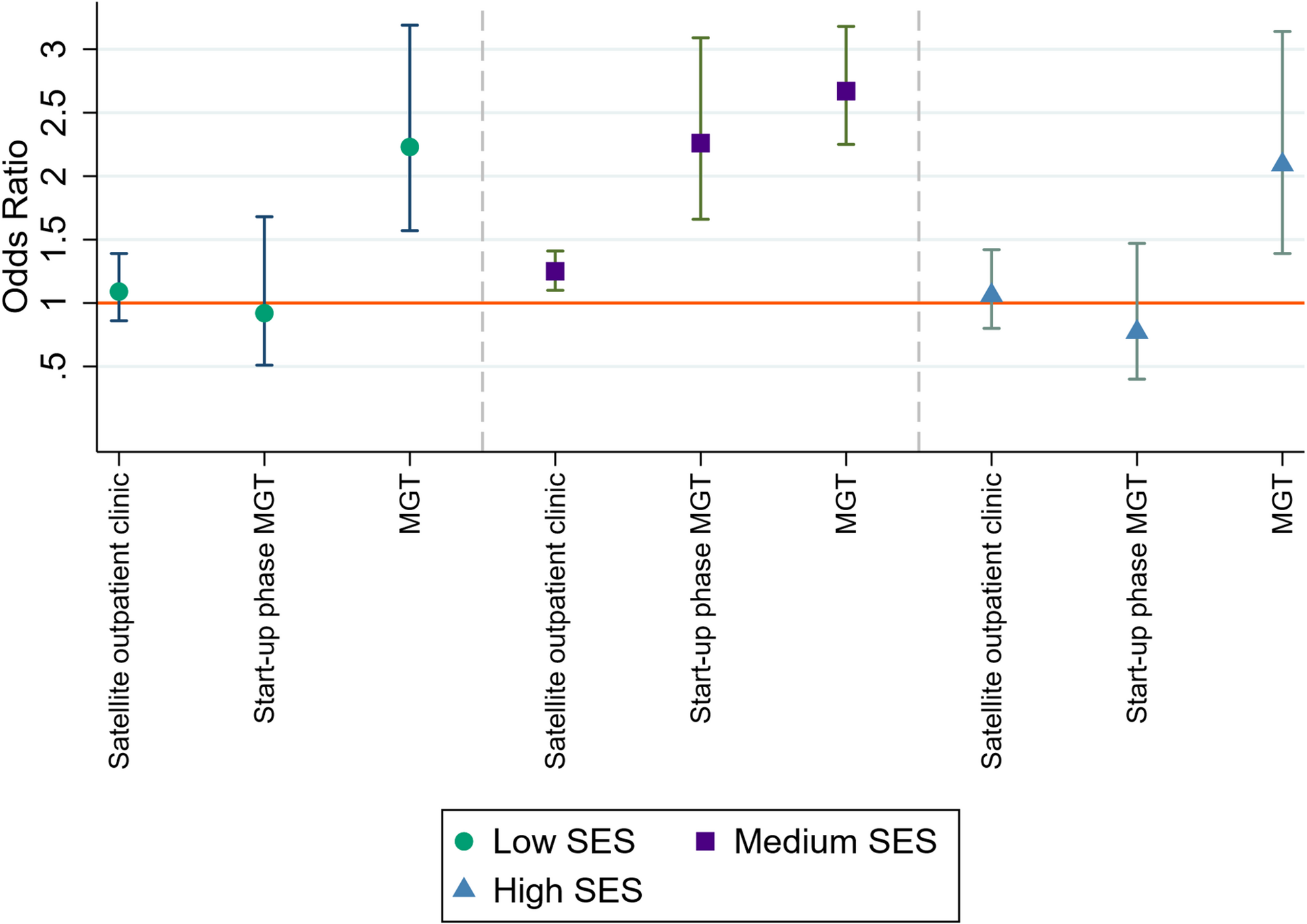

Three pathways to access to genetic testing apply in the Netherlands: (1) referral to a genetic HCP in one of the eight hospitals with a genetics department (seven UMCS – university medical centres – and the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek cancer hospital), (2) referral to an academic genetic HCP at a satellite outpatient clinic embedded in a general hospital (which is still run by genetic HCP from a genetics department) or (3) the MGT pathway, which is the pre-test counselling by the physician who is treating the patient. Information from the genetics departments indicated that a period of six months was generally considered a reasonable timeframe for the full implementation of MGT. Therefore, the MGT pathway was subdivided in the MGT start-up phase (< 6 months after the start of the implementation of the MGT pathway) and fully-implemented MGT (≥ 6 months after the start of the implementation of MGT pathway).

The organization of genetic care during the study period was determined for each Dutch hospital, based on information obtained from the eight genetics departments in the Netherlands. At the end of the study period, 26 out of 73 hospitals had implemented the MGT pathway, compared to 3 hospitals at the start. Patients diagnosed at a hospital where patients were referred to a genetics department (i.e. from a general hospital or from the hospital in which the genetics department was situated) were categorized as ‘referral to genetics department (RGD)’. Patients diagnosed at a hospital where patients were referred to a satellite outpatient clinic were categorized as ‘satellite outpatient clinic’. If MGT was the current practice in a hospital at the patient’s date of diagnosis, a comparison was made between the patient’s date of diagnosis and the date when MGT was started. Patients diagnosed less than 6 months after the start of the implementation of the MGT pathway were assigned to the ‘MGT start-up phase’ group and patients with a date of diagnosis more than 6 months after the start of the MGT pathway in their hospital were assigned to the ‘MGT’ group.

Eligibility criteria for genetic testing

Based on the Dutch national breast cancer guideline [21] patients eligible for genetic testing were divided into four groups: breast cancer diagnosis at age < 40, triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) at age < 60, bilateral breast cancer with the first diagnosis at age < 50, or male breast cancer (Table 1). These groups were not mutually exclusive. The four eligibility criteria were included in the logistic regression model as separate binary variables, allowing for overlap between criteria. Other genetic testing criteria (e.g. family history, Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry) exist, but are not included in this study, since this data was not available.

Tumour stage

Tumours were grouped according to the TNM staging system: Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) and tumour stages I, II, III and IV. When the pathological stage was unknown, the clinical stage was used.

SES

Median household income was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Statistics Netherlands provided data about household incomes broken down by detailed postcodes for 2016, with each postcode covering an average of 17 households. Median household income was clustered into 9 groups, covering 99% of the Dutch population. SES scores were classed as ‘low’ (1–3), ‘middle’ (4–7) or ‘high’ (8–9), adapted from Van Maaren et al. [22]. Previously, SES was determined using a score derived from mean household income, the proportion of residents with low income, the percentage of individuals with limited educational attainment, and the unemployment rate [22]. However, this method is not used anymore since July 2023 due to the lack of data. The correlation between the prior methodology and the current approach is strong (r = 0.72, p < 0.0001).

Orthodox religion

The patient’s postcode was also used for determining whether a patient lived in a Reformed church municipality, as a proxy for orthodox religion. Based on a recent study [23] we created a list with the percentage of votes per municipality for the Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP), the religious orthodox Christian political party, during the 2017 Dutch parliamentary elections [24]. Municipalities were grouped based on the percentage of votes for the SGP there: ‘low’ (less than 5%), ‘moderate’ (5 to 10%), ‘high’ (10 to 20%), and ‘very high’ (more than 20%). Although the proportion of votes for the SGP in the 2017 parliamentary elections were similar to those in the 2021 parliamentary elections, mergers of various municipalities in 2019 that led to more postcodes per municipality made the 2021 parliamentary election results less accurate. We therefore only used the results of the 2017 parliamentary elections.

Travel time to genetic care

Travel time to the nearest HCP for genetic care at the time of the patient’s diagnosis (i.e. to one of the eight clinical genetics departments, a satellite outpatient genetics clinic or an MGT hospital) was calculated using the Drive Time Matrix (Geodan, version 2.1), containing all travel times between Dutch postcode areas. Travel times were grouped into < 10, 10–20, 20–30 min and > 30 min.

Statistical analysis

Genetic testing uptake was determined based on the percentage of eligible patients who received germline genetic testing. Chi-squared tests were carried out to identify differences in genetic testing uptake based on the organization of genetic care, both for eligible patients overall and for specific clinical genetic testing criteria defined by patient characteristics. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the effect of MGT and SES on the uptake of genetic testing by eligible patients. For estimating the odds ratios (ORs) of MGT and SES for the uptake of genetic testing, the four clinical genetic testing criteria based on patient characteristics (each criterion included individually), tumour stage, year of diagnosis, orthodox religion and travel time to a genetic HCP were included as confounding variables. The same confounding variables were used for estimating the effect of the MGT on the uptake of genetic testing for patients within different SES groups. To determine the effect of MGT on the disparities in uptake of genetic testing between patients in different SES groups, ‘MGT’ was compared against ‘RGD’, ‘satellite outpatient clinic’ and ‘MGT start-up phase’.

We assessed multicollinearity among predictor variables by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All VIF values were below 5 (mean VIF = 1.93), indicating no significant multicollinearity. The analyses were carried out using Stata 17.0. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.