One highlight at the 2025 Expo Japan Pavilion is Yamato 000593, a meteorite discovered in Antarctica by a Japanese team with its origins on Mars. This time capsule from an earlier age of the solar system offers insight to researchers and inspiration to us all.

A Frozen Treasure Trove for Meteorites

As well as leading Japan’s scientific research on the polar regions, the National Institute of Polar Research in Tachikawa, Tokyo, serves as a base for the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition. The Institute’s pride and joy is its collection of Antarctic meteorites. Some 17,400 such specimens are stored in the facility’s cleanroom, at a temperature of 22°C and humidity of less than 50%, to prevent contamination or deterioration. Among them are “primitive” meteorites containing information on the origins of the solar system, as well as meteorites of lunar and Martian origin.

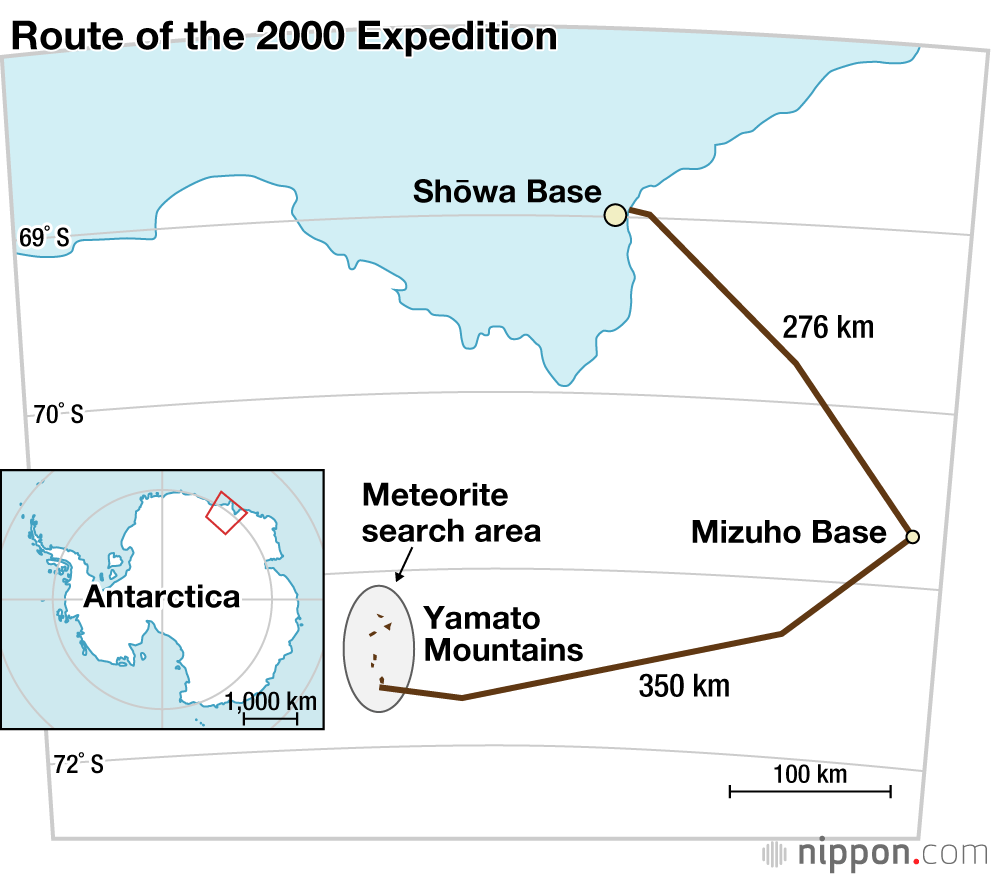

But just why are so many meteorites discovered in Antarctica? The answer lies in the giant ice sheets that cover the continent. When they happen to hit Antarctica, meteorites become embedded in the ice. The sheets flow slowly downhill, transforming into glaciers, at the rate of a few meters per year, transporting the embedded meteorites over a period of tens of thousands of years. If a sheet reaches the coast, it usually calves into the sea to become icebergs, but mountain ranges and other obstacles can block its flow of ice. In such locations, strong katabatic winds strip away surface ice, causing embedded meteorites to accumulate on the surface. In areas where meteorites tend to accumulate, particularly those composed of high-contrast blue ice, the rocks’ black color makes them stand out, meaning they are easy to spot. The area where the Yamato 000593 meteorite was discovered—near the 2,000-meter Yamato Mountains, which lie about 350 kilometers south of the Shōwa Station—is one of only a few places in Antarctica, and therefore the world, that meets these criteria.

Martian meteorite Yamato 000593 was discovered on the 2-kilometer-thick sheet of blue ice that surrounds the Yamato Mountains. The first nine meteorites discovered by Japanese explorers in 1969 were also found here. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

One of the World’s Largest Chunks of Pyroxene

The rugby-ball-shaped Yamato 000593 was found in the year 2000 by the forty-first Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition. Measuring 29 centimeters in length, 22 centimeters in width, and 17.5 centimeters in height, the meteorite weighs 13.7 kilograms, making it one of the largest single Martian meteorites ever discovered on Earth. (A portion was subsequently removed for research and educational purposes, which is why the meteorite on display at Expo 2025 only weighs 12.7 kilograms.)

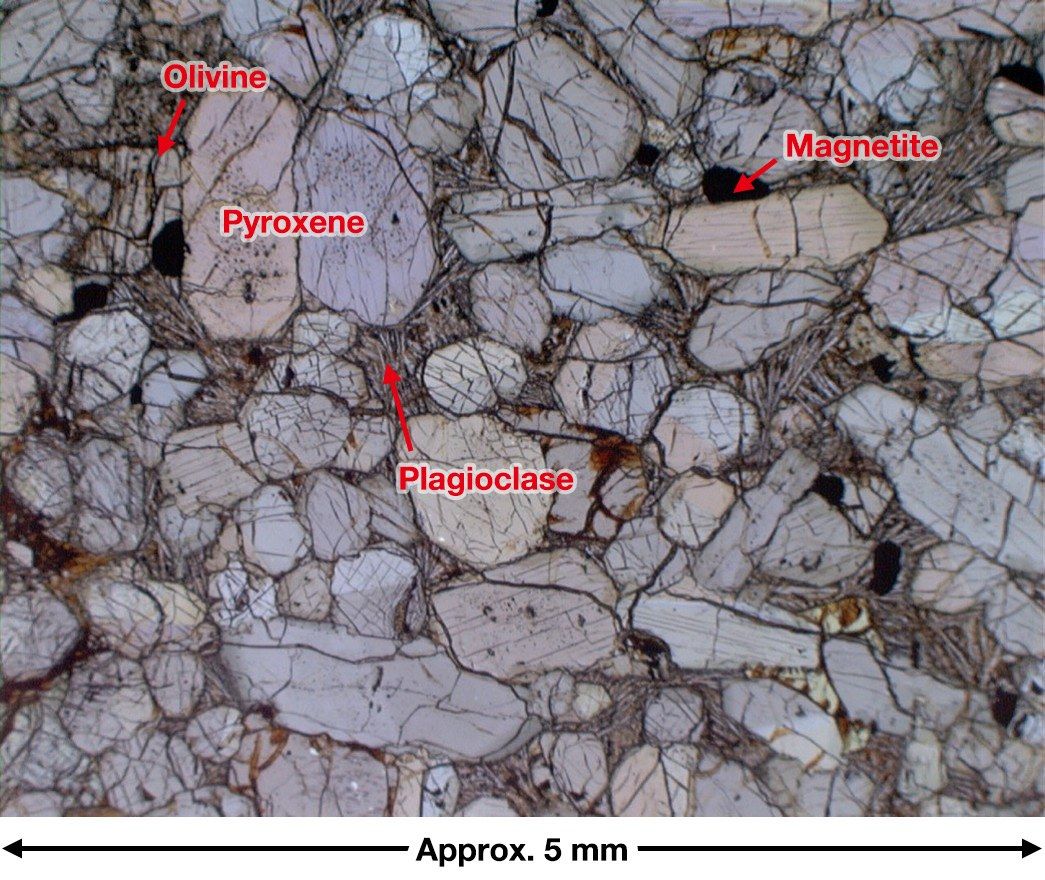

The rock is a type of Martian meteorite called a nakhlite. Chiefly formed of greenish monoclinic pyroxenes, a nakhlite is a type of igneous rock formed by the slow cooling of basalt magma, so brittle that it splinters when moved. Yamato 000593 is the world’s largest nakhlite specimen, a fact that gives it tremendous scientific value.

Yamato 000749 (1.28 kilograms) and Yamato 000802 (22 grams), also nakhlites, were found nearby. Their remarkably similar compositions and structures make it likely that all three stones were all originally part of a single meteorite that broke up when entering the Earth’s atmosphere, especially in view of melting present only on certain surfaces of Yamato 000749.

Yamato 000593 from the side. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

Yamato 000749 (left) and Yamato 000802 were both found near Yamato 000593. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

Adventure on Ice

The story of Yamato 000593’s discovery goes back to the exploratory mission conducted by the forty-first expedition, present in Antarctica from February 1, 2000, to the same date in the following year, while overwintering on the frozen continent. Selected to carry out the mission were Imae Naoya (then a geologist on the expedition and now an assistant professor at the National Institute of Polar Research) and five others. The explorers’ goal was to find meteorites in the ice sheet surrounding the mountain range.

The team travelled on three large snowcats that towed a total of 22 sleds carrying fuel, food, scientific equipment, living quarters, and meteorite storage space, creating a kind of caravan on ice. Departing the Shōwa Base on October 27, 2000, the expedition travelled 630 kilometers each way via the Mizuho Base.

The journey inland was extremely difficult. For a start, the explorers’ progress was hindered by the undulating sastrugi (undulating terrain) formed when strong winds carve depressions in snow and ice. At one point, the team encountered a series of hard, sharp ice chunks, forcing it to drive carefully at around 5 kilometers per hour. They also had to avoid crevasses tens of meters deep while facing exhaustion in the minus 15˚C conditions. On one occasion, a sled carrying food fell down a concealed crevasse and was left dangling. Working together, the explorers were able to retrieve the sled without losing any of their food, and continue their mission.

Finally, 19 days after the explorers had set out on a journey plagued by many difficulties, the Yamatos finally came into view. The ancient blue ice surrounding the mountains presented an air of mystery. After a short break, the explorers began their 54-day search. Travelling in three snowmobiles, they traversed the ice, searching for meteorites. One day in November, the team discovered a 51-kilogram meteorite composed chiefly of iron. All delighted at the discovery of what was at the time the largest meteorite ever found in the Yamato mountains. During the excitement, another large rock (Yamato 000593) was found just 500 meters away. While the explorers could tell that it was a stony meteorite, they would need to wait for analysis to discover its true value.

Assistant Professor Imae looks back on the discovery:

“When we found the meteorite, its unique greenish hue was striking. I knew instinctively that it was one I had not seen before. As soon as we got back to Japan, we analyzed it.”

Three snowcats pulled a total of 22 sleds on the search for meteorites. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

Three snowmobiles drive alongside a snowcat. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

Photo from when Yamato 000593 was discovered. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

A Martian Time Capsule and a 1.3 Billion Year Journey

Upon its arrival in Japan, Yamato 000593 underwent detailed analysis at the National Institute of Polar Research. State-of-the-art technologies let scientists confirm that the rock was of Martian origin. This was possible because the meteorite contained rare gas isotopes, in addition to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, matching the profile of the Martian atmosphere observed by the Viking probe in the 1970s. This was solid evidence that Yamato 000593 had absorbed the Martian atmosphere as it was being formed.

The team also discovered that the meteorite contained clay minerals. Because these minerals are generally created upon reaction with water, it suggests that when the rock was on Mars, there was probably water near the surface—evidence that Mars was once temperate and humid.

Additionally, the scientists unlocked the secret of the meteorite’s epic journey. Radiometric dating found that the meteorite solidified around 1.3 billion years ago, composed of magma from the Martian mantle that cooled near the planet’s surface. Using cosmic-ray exposure dating, the team also calculated that the rock was exposed to space for around 10 million years. In other words, around 10 million years ago, Mars was impacted by a giant object that caused debris, including Yamato 000593, to be flung into space.

Having escaped Mars’ gravity, Yamato 000593 floated through space, orbiting the sun while gradually approaching the Earth’s orbit. It finally succumbed to Earth’s gravity, broke through the atmosphere, and fell onto the Antarctic ice. Interestingly, a total of 29 meteorites believed to have broken away from Mars around 10 million years ago have been discovered on Earth to date, supporting the theory that a major collision event took place on the red planet at this time.

This optical microscope photograph of Yamato 000593 shows that olivine in the rock’s interior has been partially transformed into clay minerals. (Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research)

Unlocking the Solar System’s Mysteries

Yamato 000593 is just one of a number of meteorites known to have originated in Mars. The National Institute of Polar Research Antarctic meteorite collection as a whole holds immeasurable value for science. Many of the specimens in the collection are so-called primitive meteorites, formed around 4.6 billion years ago. This is considered to be around when the solar system was formed, meaning that such meteorites may be described as fossils from the origin of our solar system, more or less preserving compounds made from the dust and gas that existed before planets were formed.

Analysis of these meteorites will enable us to answer fundamental questions, like how the sun and the planets came to be formed, and how organic compounds came to give rise to life on earth. Every meteorite is an important piece in the puzzle of the birth of the solar system. The collection will also be extremely important as a control when analyzing the samples collected from the Ryūgū asteroid by the Hayabusa 2 probe. Comparing compounds that have different origins but that date from the time of the solar system’s formation will improve our understanding of the diversity and universality of the system’s material evolution. The Japanese research team continues to search for meteorites in Antarctica, in what is a continually evolving field that promises still further discoveries as analytical technologies improve.

Experience the Scale of the Universe for Yourself

The Yamato 000593 meteorite can be viewed at Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai. More than just an unusual rock, Yamato 000593 is a messenger that was born 1.3 billion years ago on Mars and spent 10 million years travelling through space before reaching Antarctica and being discovered by Japanese explorers. The rock’s interior contains a record of Martian water reserves and the evolution of the solar system.

I would love you to see this fragment of Mars for yourself. Experiencing its presence and texture and the epic story that it contains within will give you a new perspective on the expanse of space, the miracle that is the Earth, and the human spirit of discovery.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Yamato 000593 was discovered by Japanese Antarctic explorers. Courtesy the National Institute of Polar Research.)