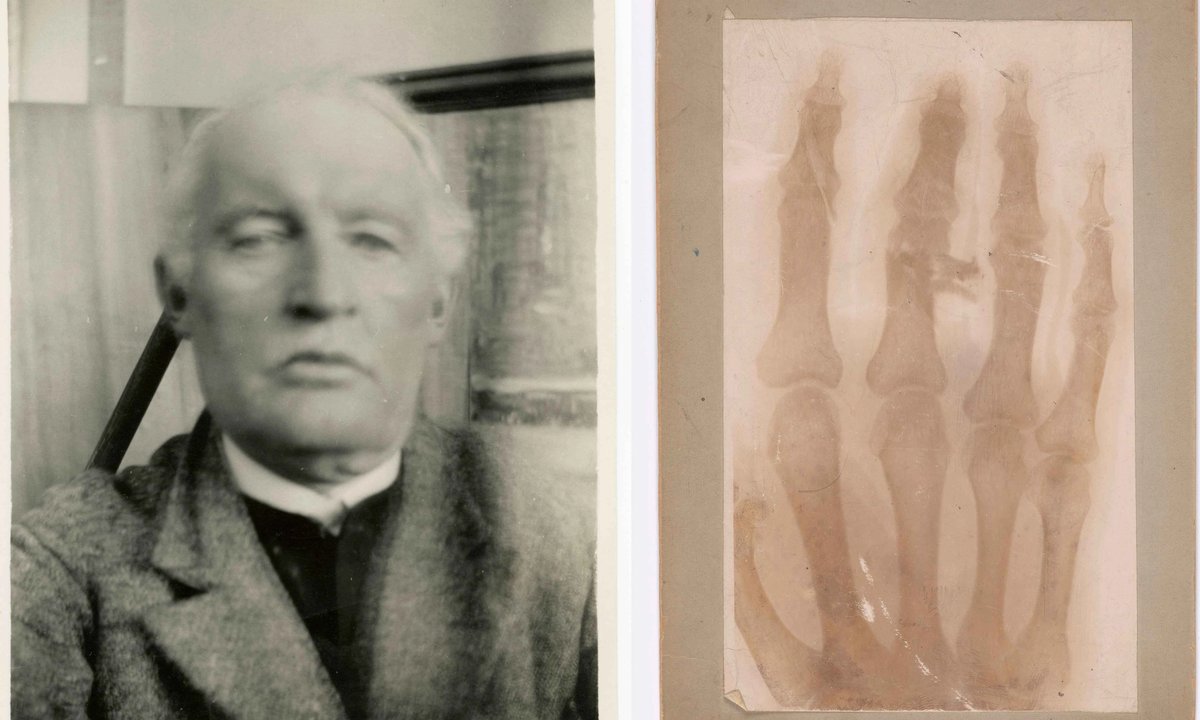

In September 1902, after an altercation with his fiancé Tulla Larsen, Edvard Munch was admitted to Norway’s national hospital to remove a bullet from his left hand. Exactly who pulled the trigger remains unclear, but the resulting surgery inspired him to paint On the Operating Table (1902-3), depicting a prone, emasculated naked body observed by a nurse, three doctors and an audience of medical students. A large red blob of blood hovers in the foreground, taking on a life of its own—suggestively shaped like a head a heart or even a uterus. The traumatic injury was also the subject of one of the very first medical X-Ray photographs, in which the bullet can be seen lodged in the artist’s ring finger.

The disquieting pairing of this gory painting and the X-ray image of Munch’s skeletal hand form a dramatic opening salvo to Lifeblood, a fascinating exhibition at Munch museum which offers new perspectives on Munch and his work by juxtaposing his paintings, drawings and prints with evocative objects from the history of healthcare, all of which in various ways pertained directly to the artist himself.

Edvard Munch, On the Operating Table (1902-3) Photo: Juri Kobayashi. Courtesy of Munchmuseet

Munch is already well known for his emotive depictions of illness, death and emotional distress. What this show and these attendant artefacts strikingly reveal, however, is how his work also intertwines with an intense lived experience of illness and a closely personal involvement in medical developments of the time.

During Munch’s lifetime, innovations such as x-ray photography, anaesthesia, germ theory, antibiotics and contraceptive devices revolutionised the perception of the body, and from an early age the artist took a keen interest in medical developments.

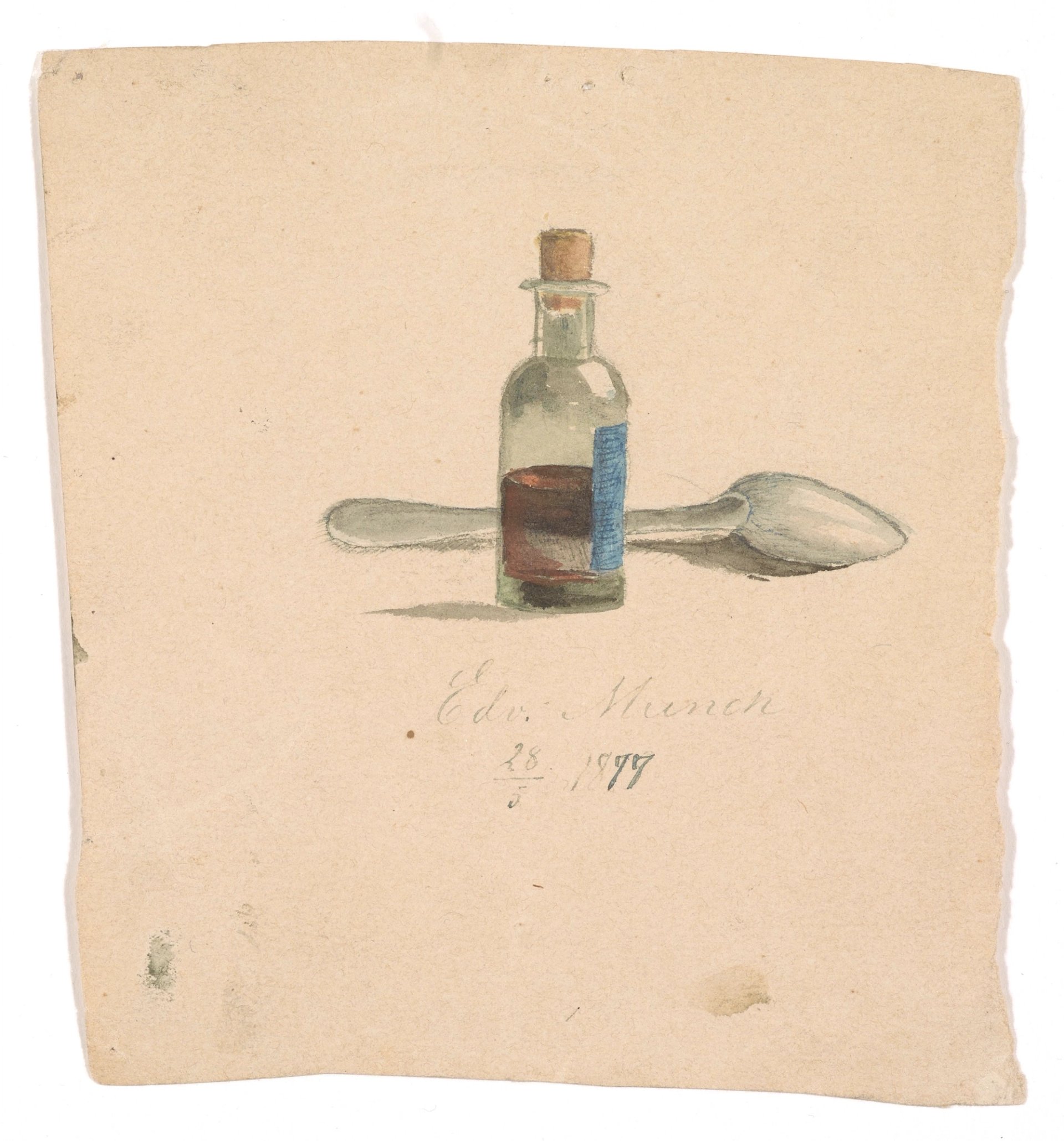

His father and his brother were doctors and as a child, Munch ran errands to the pharmacy and accompanied his father to the hospital and on home visits. Lifeblood includes several exquisite tiny watercolours a 12-year-old Munch made of bottles and jars and the interior of an apothecary’s shop, shown with some of the objects he would have encountered in these places, including a jar of arsenic painted with a warning skull and a blue glass bottle of “tinctura antihysterica”. Also featured are medical shopping lists as well as some of an apparent abundance of family letters discussing health and treatments—including a touching exchange between his parents about getting young Edvard vaccinated against smallpox.

Edvard Munch, Medicine Bottle and Spoon (1877)

Photo: Tone Margrethe Gauden. Courtesy of Munchmuseet

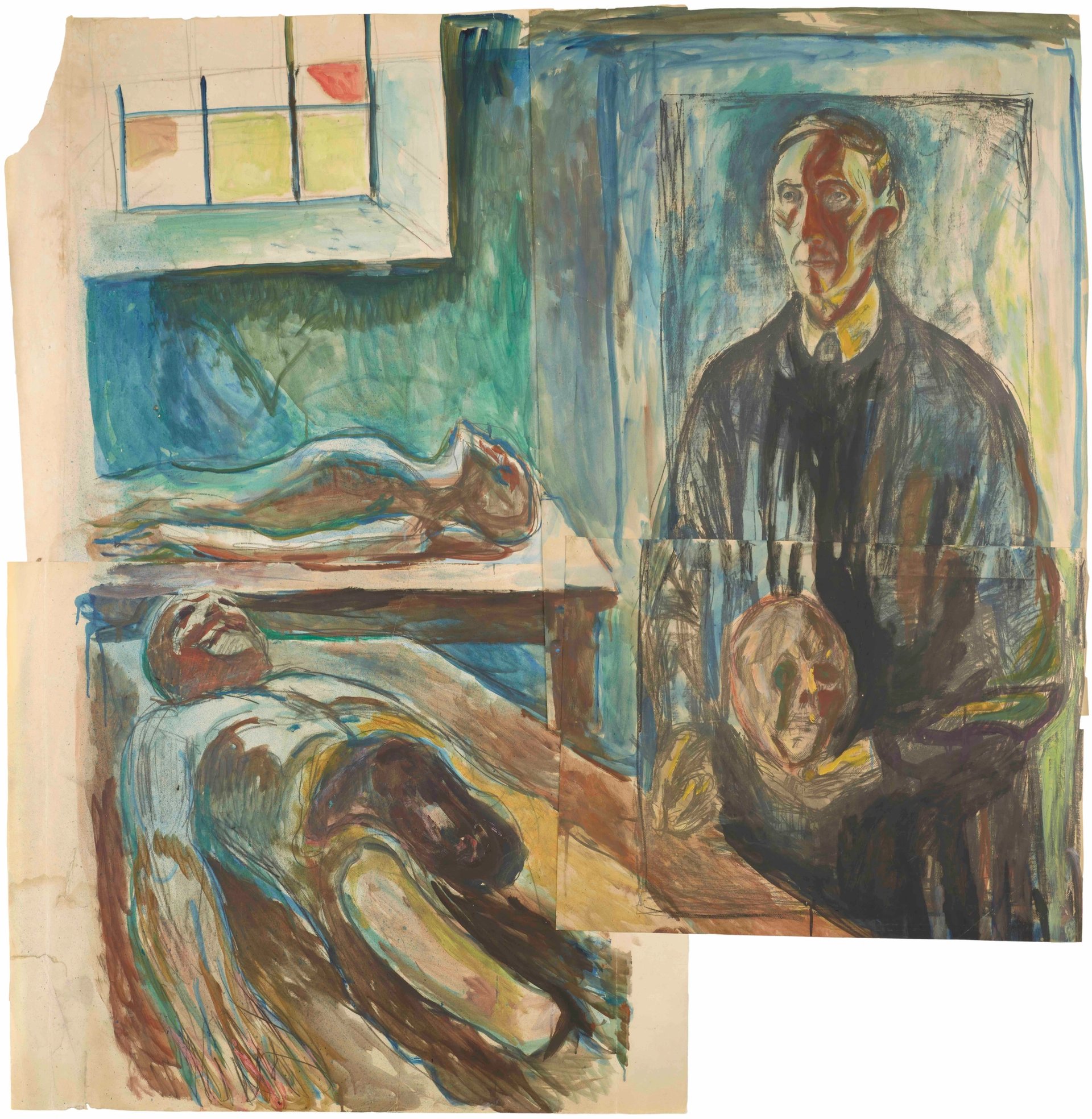

Munch maintained close relationships with doctors throughout his life, which allowed him to visit the homes of people who were sick and enter medical institutions. He would sketch and paint patients, doctors and nurses, along with loved ones gathered around a death bed. The intensity of Munch’s direct encounters with sick rooms, as well as his own experiences of illness and death, inspired some of his greatest works, many of which are included in Lifeblood. They include his original version of The Sick Child (1885-6), which—although always associated with the artist’s memories of losing his sister Sofie to tuberculosis—was also modelled on Betzy Nilsen, a distinctive red haired girl whom he had encountered on a house visit with his father.

Lifeblood roots these works in a harsh reality by bringing them into contact with many objects related to tuberculosis, which, despite improving diagnostic techniques, was still running rampant through Europe at the time. Munch would have known the mask and early stethoscopes shown here very well, and would have also been familiar with the blue glass sputum bottles, used for discrete coughing—a means of avoiding the stigma of the disease. These objects take on even stronger resonance today, in light of the recent Covid-19 pandemic.

The “black angels“ in Munch’s work

Munch was haunted by Sofie’s death and also that of his mother, who died from tuberculosis when he was five. Later he lost his brother Andreas, who succumbed to pneumonia at the age of 30. From early childhood and throughout his life Munch himself also suffered from recurrent and often serious respiratory disorders, along with many other ailments, for which he repeatedly sought treatment in various hospitals, sanitoria and spas.

He declared that “disease and insanity and death were the black angels that stood by my cradle.” One of the most powerful juxtapositions in this exhibition is that of his Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu of 1919—which shows the ashen faced artist gasping for breath—beside a case containing his breathing equipment. The oxygen tank, hoses and two masks, which Munch acquired the following year, were the very latest in modern breathing apparatus of the time—and he used them until his death from pneumonia in 1944.

Installation view of Edvard Munch: Lifeblood showing Munch’s Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu of 1919 beside a case containing his breathing equipment

Photo: Ove Kvavik

Munch’s constant dread of lung disease went hand in hand with his fear of mental illness; he worried, for example, that he and his siblings had inherited their father’s melancholy and nervous nature. Munch’s sister Laura was in and out of psychiatric institutions for most of her adult life and in 1908-9 Munch himself was admitted to a “nerve clinic” in Copenhagen, following a breakdown caused by his excessive drinking. Personal concerns also meshed with artistic interest: Munch met several psychiatrists in Paris in the 1890s who gave him access to hospitals, enabling him to observe and depict different forms of mental distress.

The many works addressing mental health in Lifeblood confirm that Munch regarded emotional suffering with empathy as well as curiosity. The accompanying material, however, also highlights how he engaged with a gendered perception of mental ill health, in which women are depicted in institutions as pitiable victimised figures while men appear in broodingly contemplative states of mind, associating them more with free-spirited creativity and genius.

A barred window from Gaustad psychiatric hospital, where Munch’s sister Laura was incarcerated, is built into one of the walls of the exhibition, offering views in and out of the surrounding rooms. This artefact—along with a basic table loom used for occupational therapy—hints at how different the hospital was from the comfortable accommodation and personalised care on offer at Munch’s private Copenhagen clinic. There, in premises more resembling a hotel than a hospital, the artist received the latest in electrical therapy, and turned his bedroom into a studio, subsequently painting two full length portraits of the clinic’s owner, the flamboyant Dr Daniel Jacobson.

Installation view showing a view through a barred window from Gaustad psychiatric hospital, where Munch’s sister Laura was incarcerated

However, Lara is still given voice—and agency—through the skilled, intricate band weaving which she sold from Gaustad, as well as through some of the detailed letters she sent home. The letters, reminding family members of appointments and taking a keen interest in household matters, highlight how Lara was an active and engaged carer—and far from a passive victim.

For Munch and his contemporaries sexual health was another major cause for fear, as well as a source of stigmatisation for women. The artist was famously afraid of syphilis and a multitude of mixed messages emanate from his brooding 1895 Madonna, which depicts a femme fatale framed by, but also separated from, a decorative border featuring swimming spermatozoa—while a glowering foetus crouches in one corner of the work. This lithograph—and another series of vampiric women depicted by Munch and his contemporaries—shares a space with a vitrine containing various contraceptive devices, including packets of “Venus” and “Casanova” condoms.

Munch’s profound fear of sexually transmitted disease and its consequences is given chilling expression in his painting Inheritance (1897-99) in which a pallid sickly newborn, their chest speckled with blood, sprawls on the lap of a mother, who coughs into a handkerchief. Munch claimed the painting was influenced by a visit to the St Louis syphilis hospital in Paris, where he apparently witnessed a mother receiving the news that her baby was fatally infected with the disease.

While there, Munch also viewed the hospital’s extensive collection of hyper-real wax models taken from casts of syphilitic babies and diseased adult body parts. Some of these models are now on loan to this exhibition and, viewed in conjunction with Inheritance, make for terrifying and tragic viewing.

A modern message

Throughout the exhibition it becomes increasingly clear that Munch was not only deeply interested in matters of healthcare but that he also saw his art as sharing some of the same aims and aspirations as modern medicine. Munch called his art his “lifeblood” and it is an apt choice of exhibition title. “When I paint illness” he wrote in his 70th year, “it is a healthy reaction that one can learn from and live by…” Elsewhere he continued this healing theme, stating that “in my art I have tried to explain life and its meaning to myself. My intention has also been to help others clarify their own lives.”

At the same time, however, Munch’s feelings about medicine were also deeply ambivalent and nowhere is this more strongly expressed than in the preponderance of skeletons that, right from the beginning, populate both Munch’s work and this exhibition.

Edvard Munch, Anatomy Professor Kristian Schreiner (1928–32)

Photo: Ove Kvavik. Courtesy of Munchmuseet

One of the show’s final exhibits is a lithograph self portrait, Dance of Death (1915), in which the artist cuddles up to a grinning skeleton who rejects his advances. As Munch jokingly quipped to his friend, the anatomy professor Kristian Schreiner: “Here we are, two anatomists sitting together; an anatomist of the body and an anatomist of the soul.” Thanks to this exhibition and its deftly selected artefacts we are given greater insight into his remarkable explorations of both.

- Edvard Munch: Lifeblood, Munch museum, Oslo, until 21 September