I caught a glimpse of the satellite as it flew over Ireland, just weeks before it bursts into flames.

Nearly two years after being launched into space, Ireland’s very first satellite mission is about to come to a close.

Throughout its lifespan, the tiny cuboid satellite, called EIRSAT-1, sent down troves of data to ground control at University College Dublin (UCD), sharing what it found about the secrets of the universe, while setting up the precedence for more student-led Irish space projects to come.

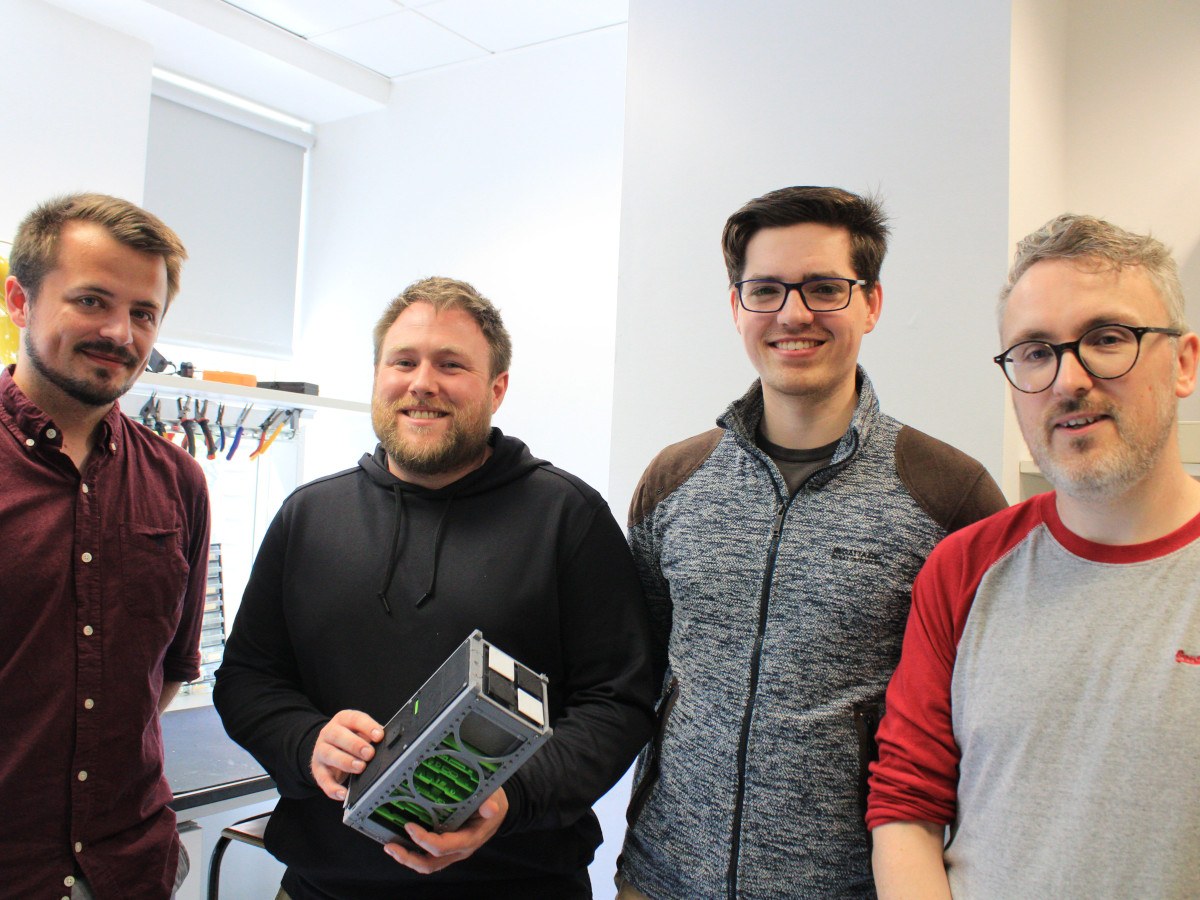

Recently, SiliconRepublic.com visited mission control at UCD – a small office laden with computers – to meet with the team behind the project.

“It’s the first Irish satellite and something that we’re very, very proud of,” says Dr David Murphy, the satellite’s systems engineer and a research fellow at the UCD C-Space, Centre for Space Research.

The EIRSAT-1, or Education Research Satellite-1’s story began back in 2017 through the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Fly Your Satellite! program.

The UCD-led project received support from Queen’s University Belfast and a number of Irish space tech companies.

In its time, the satellite detected nearly a dozen gamma ray bursts and a few solar flares, and the team tells SiliconRepublic.com that they are already developing newer projects that build on what they learnt from this small – yet large – leap into Ireland’s achievements in space science.

Late last week, UCD announced another ESA-funded space project which is set to send a swarm of satellites to the Earth’s orbit to detect more gamma ray bursts. Murphy has been working on this new project, called Comcube-S, for a while now.

The making of

Over the years, more than 60 people, comprising of students and early-career researchers, helped create EIRSAT-1. At its tail end, the project has about 10 active contributors.

Nearly six years of development went into building and testing the EIRSAT-1, including several months where the team had to work remotely as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

They received support from various government agencies through grants, as well as through Prodex, an ESA programme that supports university space projects.

Using this, they were able to fund their research, test the spacecraft and provide scholarships for their contributors.

However, after some unavoidable legislative setbacks and launch delays later, the satellite finally took to space in late 2023 on the ESA’s Vega-C rocket.

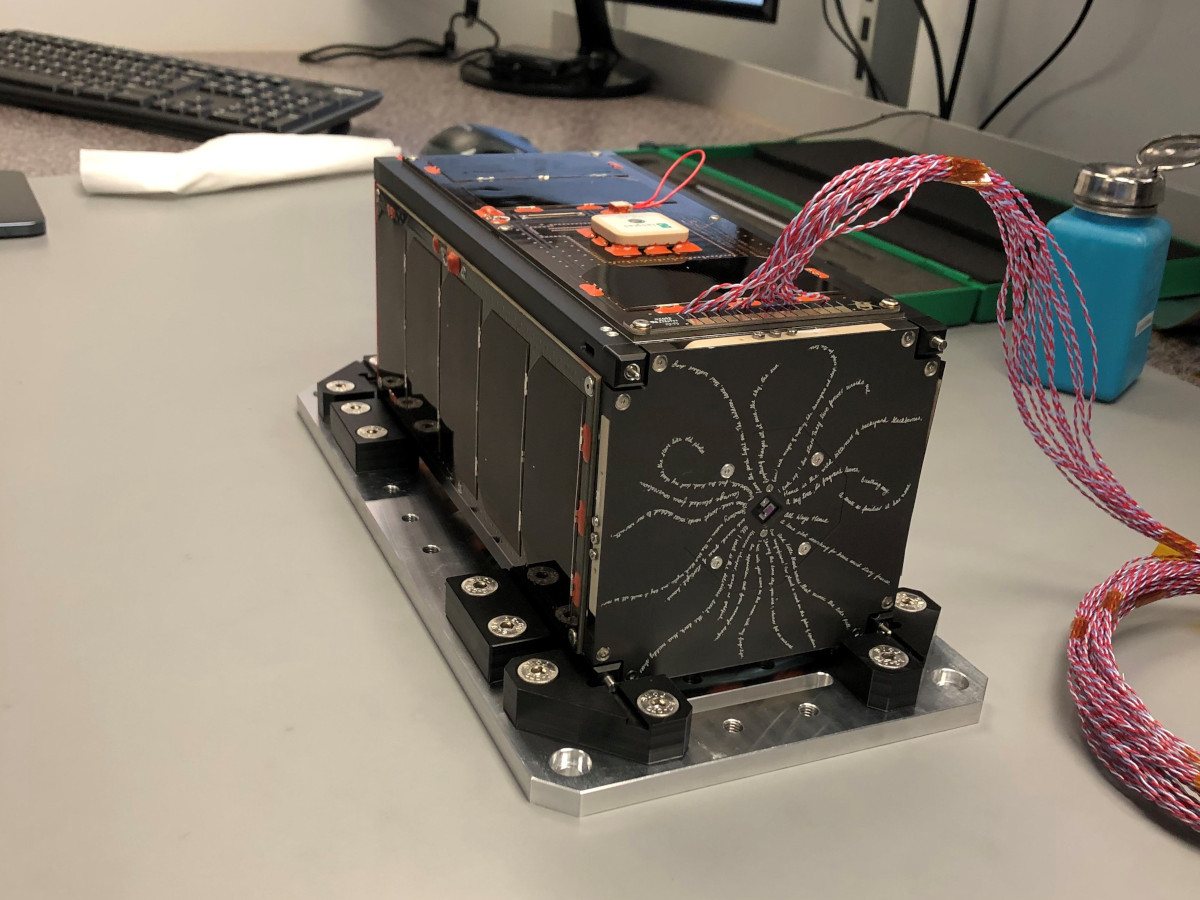

EIRSAT-1. Image: ESA

The EIRSAT-1 has a length and width of about 10.6cm and a height of 22.7cm. Inside its small aluminium body, the spacecraft is fitted with parts that help navigate and orient itself and collect data and send it back down to Earth.

A few of these complex parts include a magnet worker that lines the satellite to Earth’s magnetic field, a “very, very cool” antenna deployment mechanism, as pointed out to me by Murphy, a gamma ray detector and a sun sensor, which shows the accurate angle between the sun and the spacecraft.

The satellite is covered on all sides with solar panels. Some of its body is anodized – or coated with a protective oxide layer – which ensures that the aluminium parts do not cold weld with parts of the rocket.

Using this tiny complicated box floating alone in space, the scientists at UCD were able to detect around a dozen gamma rays – up from two when I last spoke to Murphy near Christmas last year. They also detected two solar flares.

“[Gamma rays] are the most luminous explosions in the universe,” Caimin McKenna, a current PhD student in the Space Science Group at UCD tells me. These rays are produced by the hottest and most energetic objects in the universe such as neutron stars and supernova explosions.

McKenna, 25, was pursuing his undergraduate degree when calls were put out for students to join the EIRSAT-1 programme.

Although, after the first few successful sightings, gamma ray detection “turned into work”, the team told me, laughing. Still, they were excited for more.

Interception

Our conversation was briefly diverted when the EIRSAT-1 neared Ireland overhead at around 12:40 pm that afternoon.

Each day, the satellite sends data it collects while flying over the country via two on-ground communication systems – one above the UCD building we were at, and one in a goat farm in Co Kerry.

The small control room is fitted with several computers. On one monitor, I could see the tiny satellite approaching Ireland, while on a larger one on the wall, I could see faint red bands, which got darker and more prominent as the satellite neared us.

EIRSAT-1 control room, UCD. Image: Suhasini Srinivasaragavan

The two-way communication happens through amateur radio frequency bands. The team sends audio tones to the spacecraft, which it can decode into commands, sending back the requested data.

“Essentially, it’s sending beeps and boops,” Murphy tells me. The beeps and boops contain troves of scientific data. “It’s like a constant stream of data down from the spacecraft to us.” The EIRSAT has made hundreds of such rounds.

However, less than two years after being thrusted into space on a rocket, this tiny spacecraft wandering the Earth’s orbit is set to burn up in the atmosphere. “It’s essentially spiralling down to Earth”, Murphy tells me. “We’ve got weeks left now”.

“It’s sad on one side that you know, it’s burning up and it’s only been about a year and a half since we launched,” Dr Joe Thompson, the project’s chief engineer tells me.

“But on the other side, we have to be very happy with how successful it all was. It’s surpassed all of our expectations.”

Although, the team isn’t entirely sure when the satellite will burn up. “At some point, I think a bunch of people are just going to be sitting around in the room wondering ‘Is this the last time we talked to her?’,” Thompson says.

While the team is sad to see “her” go, they tell me that they’ll do something to commemorate the journey and its end.

All Ways Home

The EIRSAT-1 story isn’t just a victory for the dozens who developed and launched the spacecraft. It’s a win for the wide-eyed ones among us who stare up at the sky wondering what it all means.

It’s a win for Ireland, which has showcased the calibre of its academic prowess, creating the precedence for a potential space program of its own one day – hopefully.

It also gave bragging rights to Thompson’s nephew who told his class that “uncle joe” went to California to launch a rocket.

Although the brains behind the project were sitting at UCD, EIRSAT-1 received support from school children across the country who poured their creativity to design special mission patches.

A few design submissions for the EIRSAT-1 mission patches. Image: Suhasini Srinivasaragavan

12 DEIS secondary school students, along with contributors from UCD, also wrote a poem, entitled ‘All Ways Home’ which is etched onto the side of EIRSAT-1.

All Ways Home

A lone pilot searching for home amid starry frescos,

And little blood waves that mimic the tide-pull.

Our insignificance! Our planet a crumb on the fabric of spacetime,

Sharing the same sky, you and I, wherever feet are anchored.

I will write your name on the moon with my fingertips,

An apparition cast from memory’s design.

Universe-whisper, orange as goldfish.

All I want is the delicious scent, the dark blue muddy shoes

and ruined grass of starlight, home.

Strawberry moon in the cloudless, blue black mystic, one day it could all be rain.

Those wind-swept words; voices clutched to our warmth,

Courage plucked from conversation.

Breezebreath, feel the blush dust my cheeks, the stars like old photos.

Leave the porch light on. The children dance, their mothers sing.

Everything changes all at once, the sky, the sun.

Bound with images of mystery, like lemongrass and sleep, except for the tree.

I look up. I see stars. They live forever inside me.

Home is the wild bitterness of backyard blackberries,

A bay tree, its fragrant leaves,

Breathing easy,

A smell so familiar it has none.

Don’t miss out on the knowledge you need to succeed. Sign up for the Daily Brief, Silicon Republic’s digest of need-to-know sci-tech news.