Using psychedelics to treat psychiatric diseases has become less controversial as scientists continue to reveal their underlying mechanisms. In a new eNeuro paper, researchers led by Pavel Ortinski, from the University of Kentucky,…

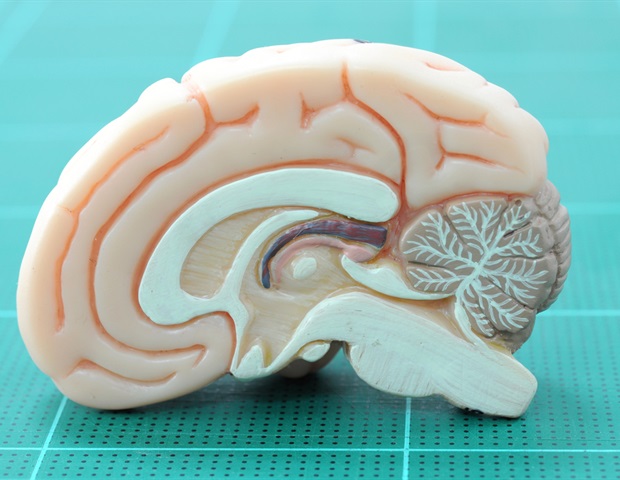

Exploring the role of the claustrum in psychedelic-induced memory enhancement