Anita Lasker-Wallfisch has spent an entire century on this earth, and does not fear death. After all, she’d often looked it in the eye when she was deported to Auschwitz simply for being a Jew. It was the largest and most notorious of the Nazi concentration and extermination camps. There, around 1.1 million people were killed on an industrial scale, reports DW.

Lasker-Wallfisch survived because she could play the cello.

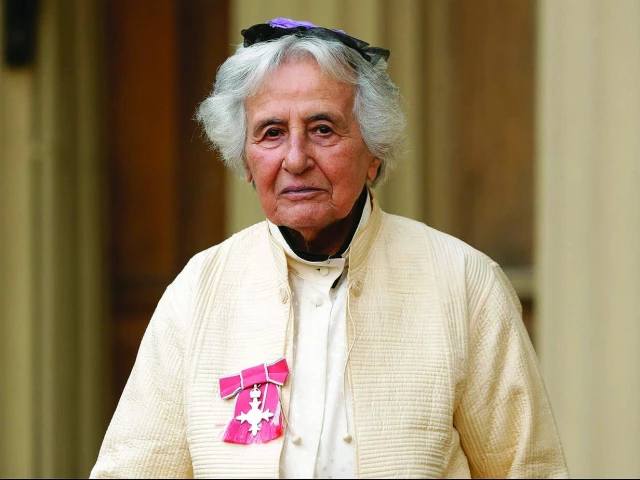

For decades, she has raised her voice against antisemitism, right-wing extremism and racism as a dedicated witness to history. She has told scores of schoolchildren unsparingly how the Nazis systematically marginalised Jews and ultimately murdered them. She feels it is a duty “that those who survived must serve as voices for the millions who were silenced.” That’s why she has also taken part in the Dimensions in Testimony project, in which interactive holograms enable Holocaust survivors to answer questions even after their deaths.

Lasker-Wallfisch and her sister, Renate, had to work as forced laborers at a paper factory. She used this opportunity to forge documents for other forced laborers from France, enabling them to return to their homeland. In 1943, when the two sisters tried to flee with forged passports, they were imprisoned. Five months later, they arrived separately at Auschwitz.

Because Lasker-Wallfisch could play an instrument, she was assigned to the girls’ orchestra at Auschwitz. “The cello saved my life,” she later said. When the forced labourers left the camp in the morning and returned in the evening, the orchestra played music for them to march to. On Sundays, the girls performed for the SS.

“Not a single one of us believed we’d make it out of Auschwitz in any other way than up the chimney,” were her words. In 1944, when Soviet troops were advancing on Auschwitz, Lasker-Wallfisch and her sister were moved to the extremely overcrowded concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, where people died of hunger, thirst and disease. “Auschwitz was a camp that systematically murdered people,” she later wrote in her memoirs, “in Belsen, you just died.”

A long silence

In September 1945, she testified against the Lasker-Wallfisch at Bergen-Belsen before a British military court. It would be a long time until Lasker felt able once again to speak of her experience.

She emigrated to Britain in 1946. In London, she became a founding member of the English Chamber Orchestra and played in this ensemble until the turn of the century. She married pianist Peter Wallfisch, who, like her, was from Breslau. He had emigrated to Palestine as part of he Kindertransport (German for “children’s transport”) — an organised rescue effort of mainly Jewish children from Nazi-controlled territory. The couple did not speak to their children about the past. When her daughter, Maya, asked her mother why she had a phone number tattooed on her arm, she responded “I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

After many decades, Lasker-Wallfisch was ready to tell her story. Her book Inherit the Truth 1939-1945: The Documented Experiences of a Survivor of Auschwitz and Belsen was published in 1996. It made her internationally known as a witness to history.

In 2018, on the German Day of Remembrance for the Victims of National Socialism, Lasker-Wallfisch gave a fiery speech in the country’s parliament, the Bundestag, admonishing people not to forget. She said she perceived an increasing societal sentiment to leave such things in the past. Lasker-Wallfisch continued, “What are we meant to draw the line under? What happened, happened, and it cannot be expunged by drawing a line.”

Now Lasker-Wallfisch is turning 100. A concert is being held in her honour in London. Dignitaries from all over the world are coming to congratulate one of the last living witnesses of the Holocaust. Her daughter Maya, son Raphael, grandchildren and great-grandchildren will also toast her. But what’s important to the centenarian isn’t the extravagant celebration. What Lasker-Wallfisch desires above all is that the poison of hate and antisemitism be eradicated once and for all. A wish that is, unfortunately, not so easy to fulfill.