A stolen glance across a crowded room, a shadowy figure slipping through a doorway, a lover hidden behind a curtain – adultery has long been a drama of secrecy. From Renaissance masterpieces to tabloid snapshots, the act of romantic betrayal has not only shaped personal lives but also left its mark on art history. Painters across the centuries have turned this most intimate of transgressions into art, inviting viewers to become voyeurs of passion, guilt and desire.

Historically, artistic representations of adultery have been used to raise questions about the importance of love and sexual desire in marriage. Artists have also used their works to explore themes of culpability and punishment, and to explore the consequences of infidelity for the families of the adulterers.

Renaissance and Baroque artists picked up on the theme of adultery by depicting episodes from the Bible. Portraying scenes that were set in eras during which the punishment women faced for adultery was death, artists including Rembrandt, Rubens and Tintoretto, explored religious disciplinary processes and the difficulties of pronouncing moral judgments.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Rembrandt’s The Woman Taken in Adultery (1644) tells the story of how Christ’s compliance with Jewish law was put to the test by a council of Pharisees (members of a biblical Jewish sect who were fanatic about obeying religious laws), who bring an adulteress before him.

The punishment for her crime according to Mosaic law was to be stoned to death. Christ’s response, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her,” emphasised the moral hypocrisy of the men who stood as judges.

National Gallery

Although the figure of Jesus is prominent in the painting, the adulteress is central. She appears penitent, dressed in white and bathed in light – a striking contrast to the dark male figures that surround her.

That is not to say women were always portrayed as vulnerable. Throughout early modern Europe (circa 1450-1800), perceptions of women were heavily influenced by biblical figures such as Eve.

Women were largely believed to be the more lustful sex, weaker and more likely to succumb to temptation, and to be more deceptive and manipulative than men. The German Renaissance painter, Lucas Cranach demonstrated this belief in The Fable of the Mouth of Truth (1534).

The painting depicts another married woman surrounded by men who are scrutinising her. But in this case, she is not repentant. Instead, she is trying to trick her way out of receiving any punishment for her infidelity with the help of her lover, who is masquerading as a fool.

Germanic National Museum

Certain artistic genres were employed to publicise and critique changes to laws regarding adultery and divorce. For centuries, church courts dealt with marital disputes and adultery in Britain.

A full divorce (that allowed both parties to remarry) was only possible by act of parliament, which made it unobtainable for all but very wealthy men.

The art of divorce

After the Matrimonial Causes Act was passed in 1857, divorce became a matter for the civil courts, and therefore a viable option for a greater proportion of British society.

Several pre-Raphaelite artworks, including Augustus Egg’s Past and Present series, depicted the damage that infidelity and subsequent divorce could have on the family unit. Egg’s work emphasised that women, who were often ostracised and cut from their social and familial networks after divorce, were punished more severely than men for their transgressions.

Tate Britain

Satirists including James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson chose very different devices to critique laws concerning adultery when they ridiculed “Criminal Conversation”, a civil suit that was introduced in the early 18th century, and only ended with the 1857 Act.

“Crim con” allowed a man to sue his wife’s lover for robbing him of her affections and domestic support. If his suit was successful, the husband could claim financial compensation from his rival, sometimes to the tune of tens of thousands of pounds.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, such suits were most often pursued by members of the landed gentry and the aristocracy. Moreover, as they were heard in the Court of the King’s Bench, which was open to journalists and the public, the salacious details of the affairs were published in newspapers and pamphlets.

National Portrait Gallery

Crim con suits were much deplored by contemporary moralists. They emphasised the impropriety of a man receiving money from another man for the sexual services of his wife, as well as the debauchery of some elite husbands, who were viewed as being culpable and complicit in their wives’ affairs.

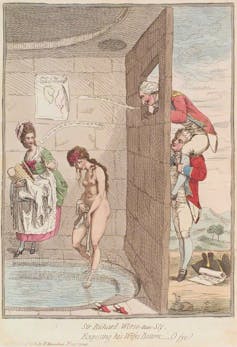

The crim con trial of Worsley versus Bisset in February 1782 attracted a considerable amount of publicity and was depicted by several of London’s best satirists. A story about the affair that inspired many satirical prints had been discussed at length in court. Lady Worsley had been enjoying a dip at Maidstone bathhouse, when her husband allegedly hoisted her lover, Captain Bisset, on to his shoulders, so that he could see her naked body.

The notion that Worsley was a voyeur who had pimped his wife out for his own delectation was so popular that it even influenced the judge, who awarded him a humiliating one shilling in damages.

The satires were meant to entertain and titillate their audiences, but they also raised awareness of the apparent profligacy of the ruling elite. Representations of the adulterous liaisons of celebrities, including military heroes like Admiral Lord Nelson, politicians like Charles James Fox, actresses like Mary Robinson, and even royals, such as George IV, were used to highlight their moral corruption, and they provided much fodder for activists demanding political reform.

The history of adultery in art draws attention to the intersections between personal relationships and the public realm. Even today, when consensual relationships between adults are not formally policed, affairs continue to prompt public discussions about private morality, ideal marriages and the suitability of casting judgment. We continue to enjoy the opportunity to moralise while being entertained by the salacious portrayals of other people’s affairs.