Fresh from the successful completion of its XB-1 flight test campaign earlier this year, TIM ROBINSON FRAeS talks to Boom Supersonic founder and CEO, Blake Scholl.

Boom Supersonic Founder and CEO, Blake Scholl. (All: Boom Supersonic)

AEROSPACE: What was your reaction on completing the XB-1 flight test campaign? Relief, satisfaction, elation at proving the sceptics wrong?

SCHOLL: Probably all of those. I think I was most buoyed by how much positive reaction there was outside of the company. It got noticed a lot more and there was a lot more excitement than I anticipated. One of my favourite things were the pictures and videos that came out of classrooms with kids glued to the screen watching it. There’s one I saw where a little girl was jumping up and down the moment it went supersonic and it just spoke to me very deeply. Somewhere, in one of those classrooms, there’s a chief engineer for Overture Three, for the hypersonic Overture and I just haven’t met them yet. Of course, the first mission is to bring back supersonic flight and to make it available for everybody. But the second mission is to be inspiring. If we can do that, it’s going to help rejuvenate aviation, inspire more great young people to go into the sector. That will pay dividends decades out. Somewhere around the ‘70s, we quit doing new, exciting things, and the result was a whole generation of young people who never went into aerospace.

AEROSPACE: It was great to see this transparency with live streaming the flight test – especially for a piloted supersonic demonstrator that did not have an ejection seat. Did you have any qualms about that?

SCHOLL: We didn’t stream the first flight for basically that reason. Nor did we have any guests or media; we didn’t tell anybody what was going to happen. The safety culture is very important to me and to Boom, and one of the crucial things is preserving the team’s ability to make their own go/no-go decisions and avoiding pressure like that, regardless of whether anybody was watching. In fact, that happened on the first flight. It was originally going to be about a week earlier than it actually was. We were under pressure to fly, but I would get in front of the team every morning and say we know it’s about time to go, but if you find a problem with the aeroplane, we most definitely want to know. We might say a four letter word, but then we’re going to say ‘thank you’, and then we’re going to say, ‘what do you need to fix it’? It turned out that was exactly what happened. The day before the planned first flight, one of our young, early career engineers said, ‘Hey, I was going through data on the drag chute’, which is really just back-up equipment and we didn’t expect to ever need it. She said, ‘I think we need to fix it.’ I said a four letter word and then said, ‘thank you for telling me. How do we get behind you and support you in fixing this?’ Her name is Grace, and we celebrate her.

AEROSPACE: What was the biggest lesson you learnt from XB-1?

SCHOLL: There’s a lot you can learn about supersonic aeroplanes by reading papers and books, but there’s a lot you can learn only by doing it. We learned what it takes to really execute a supersonic programme from scratch, to build an aircraft and to put a human on board. We learned where the real challenges are, the real break points in the technology and the cultural challenges. We learned how to build a safety culture. I’m very proud of that. For Overture, we originally started out targeting Mach 2.2 or 10% faster than Concorde. On paper, that seemed very feasible but, as we went to do it, we found out the hard thing that you won’t read about in books is that a long, skinny aeroplane, with a delta wing that is even more slender than Concorde leads to significant low speed challenges. Landing gear packaging gets much harder with a Mach 2.2 aircraft than a Mach 1.7 one because it is hard to fit it in this fuselage. We backed off the 2.2 goal to 1.7 which really means a 15 or 20 minute longer flight across the Atlantic. I hate that, but it results in a much more buildable aeroplane, low-speed handling gets easier and complying with the latest-generation take-off and landing noise standards gets much easier. Thermal management gets much easier. We are eventually going to build an aircraft that will fly faster than Concorde, mark my words – but we found a pragmatic place to start, thanks to everything we learned from XB-1. The whole point of XB-1 was to learn and Overture got much better as a result of it.

AEROSPACE: Boomless cruise was big news from the flight test. Was that something that was expected or just a happy discovery?

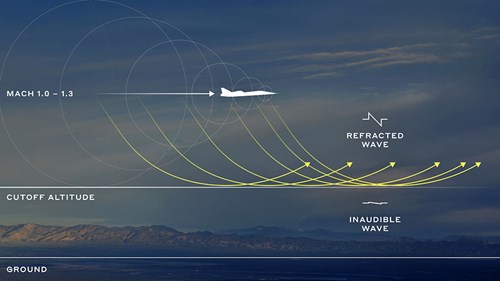

SCHOLL: We weren’t banking on it. We didn’t invent that – people have known about Mach cutoff for decades but if you can make it happen at a shallow enough angle and a high enough altitude, it makes a U-turn in the atmosphere, refracts upwards and never touches the ground. However, to do this, you need to have good enough weather data to calculate what the speed needs to be on any given day. You also need enough power to break the sound barrier at a sufficiently high altitude so that the bottom of that ‘U’ doesn’t touch the ground. Plus you need engines that are efficient enough to maintain transonic speeds without losing too much range.

Originally, we were working with Rolls-Royce but the transonic performance was not there and the highest altitude versus sound barrier was 20,000ft. Initially we decided to focus on overwater supersonic flight and come back to the overland thing later but then, along the way, we switched to our own engine and there are many benefits to that. Firstly, we get a fully optimised, custom-built aircraft and engine combination. I would meet with the engineering team regularly to discuss how the optimisation was going and in every meeting it seemed that this transonic performance was just getting better. XB-1 breaks the sound barrier because of the engine and aircraft combination; it just happens that it was easy to do it and achieve boomless cruise.

Then I thought ‘wait a minute, maybe we should rerun the maths?’ So I called an emergency engineering meeting. Everybody came in on a Saturday and I said, ‘can you rerun the maths into the Symphony engine without changing anything. Can we do boomless cruise?’ We ran the maths in the meeting and it worked – we didn’t have to do anything, it just worked. So actually, we sort of just lucked into it. This is one of many things about Overture that we never could have had if we hadn’t made our own engine.

AEROSPACE: What engine did Rolls-Royce offer?

Boom’s Symphony engine is now being built.

SCHOLL: It was going to be a scaled-up version of the three-spool core advanced Trent. However, it came with downsides because the Trent cores are optimised for a subsonic flight profile where you only need full power for take-off and then you throttle back to cruise. So, for example, the cooling architecture in the core, the hollow turbine blades, doesn’t provide much cooling flow because they’re only hot for a little while. Meanwhile, our engine will stay hot for the entire flight and take-off is actually when they’re coolest.

Now that we’re designing the engine in-house, we were able to run studies much, much faster. We looked at about a dozen different engine designs with the same basic architecture, but we’re tuning core size and fan size. We were able to generate what’s called an engine deck to test those variables and the team can just press a button and have a whole aircraft/engine combination ready for the mission simulator. We can then evaluate the aircraft through a complete mission profile to take off, climb out, accelerate, cruise, descend and land, assessing how efficient and quiet it was from a take-off and landing noise perspective.

By evaluating a lot of different engine designs quickly (which we never could have done with a third-party engine provider), we were able to find a much better design and enable boomless cruise.

It also enables a breakthrough in the passenger cabin that we haven’t shared yet. There was a breakthrough the team had about 18 months ago for a passenger cabin concept, that no one’s ever going to believe you could do. When we first looked at it, it cost 1,000 miles of range – but we got the 1,000 miles back through this engine optimisation and the passengers will get something great.

AEROSPACE: What are your recruitment priorities as you scale up and move to engine testing?

SCHOLL: We are about to grow, albeit modestly. I am a big believer in keeping the team small. For XB-1 a legacy company would have needed 500 engineers, maybe 5,000. We did it with 50 people, including engineers, technicians and pilots. I think when Overture flies, one of the most astonishing things will be how small the team was. We have a concept at Boom we call the talent distillery. It’s hard to find enough people from legacy companies who are both really good and are going to fit at a start-up culture that’s about moving fast and being innovative. What we do is build the core of the company out of young people. We find the best and the brightest – sometimes it’s interns, sometimes people graduating. Sometimes we go and rescue somebody out of Boeing at the start of their career! Those are the young spirits. Then we get just a few people with some experience that are still open-minded, and we make those people the mentors, the advisers. I think this formula really works and it means we’re building our next generation of leaders.

AEROSPACE: Are you utilising AI tools in the development of Overture?

SCHOLL: We have some custom AI tools that we can drop all the certification documentation, regulations and advisory circulars into and it writes a certification document. As an example, it takes a couple of minutes to generate a 100-page lightning strike test plan. Then it takes an engineer about three hours to review it and edit it. Previously, that would take about a month.

AEROSPACE: Why will Boomless Cruise work for Boom, if it did not work for Concorde and overland flight before?

SCHOLL: If you talk to retired Concorde pilots they’ll say they did [boomless cruise] sometimes, but it was by accident. They couldn’t do it reliably or efficiently as they didn’t have the weather data. Also the aircraft didn’t have the performance to do it efficiently – Concorde would have been in afterburner to achieve it, and that would cut the range in half.

AEROSPACE: What about noise regulations around airports? Surely that will be an issue too?

Supersonic take-off and landing noise restrictions have now been ratified by ICAO.

SCHOLL: It’s fundamental but we are going to meet the same, most stringent noise levels that apply to latest-generation aircraft. ICAO just ratified this earlier this year – with Chapter 14 noise levels that will apply to subsonic aircraft, and there’s now a Chapter 15, which sets supersonic take-off and landing noise standards globally. Applied to supersonic airliners it allows them to fly with advanced procedures to minimise noise and it turns out actually you can make the aircraft quieter. We’ve got something called the variable noise reduction system (VNRS) which is really just automated procedures on take-off and landing that configure the aeroplane to minimise the noise footprint on the ground. This means we can meet the same noise footprint. The FAA has been supportive, but we’re grateful that we have got support in Europe as well. We’re doing everything we can to create an aircraft that is easy for ATC, easy for airports, easy for airlines and easy for the community.

AEROSPACE: Is there a minimum launch number for Overture?

SCHOLL: We already cleared that number a long time ago. We had 130 aeroplanes on order and pre-order – that is the first five years of production. After that, every major international airline is just going to say ‘we need a supersonic airliner or else I can’t compete.’ We are putting zero energy into sales at the moment; if airlines call us, we tell them we’ll call them back later. We’re just focused on building the aircraft for now.

AEROSPACE: What do you say to those who question the business case for supersonic air travel? We have high-speed wi-fi now and lie-flat beds that didn’t exist in Concorde’s day.

Boom is promising a ‘never before’ seen feature for its passenger cabin.

SCHOLL: We haven’t unveiled it yet, but we have something very wonderful for the cabin and very different from Concorde. You had to duck to get onto Concorde but our cabin will be two inches taller than a narrowbody – so a 95th percentile male can step on board without bumping his head. It has not got a flatbed because it’s a three or four hour flight and you sleep much better at home than you sleep on any flying flatbed. The thing to remember here is if you are just shaving 15-20 minutes off flights it doesn’t matter – but what we’re doing is we’re turning ‘red eyes’ into daytime flights. From the US to Europe, instead of flying overnight and trying to sleep on the aeroplane, you catch a morning flight from the US, and even with the time difference, you can get to Europe in time to make a late afternoon meeting or dinner. It saves you a whole night, and you’re much better rested because you slept at home.

Concorde was great technology but the wrong aircraft. It was a 100 seat aeroplane with, adjusted for inflation, £20,000 return tickets. It is very hard to find a route where you can fill 100 seats at £20,000, so it’s not economically compatible with very many routes.

Since then, the market has got a lot bigger. The travel demand today is many times greater than it was in Concorde’s heyday and that just makes everything easier. The other thing is we shrank the number of seats, so it’s much easier to get a good load factor. People often say Concorde was too small but actually the reverse is true. We’ve been very thoughtful about making sure Overture is the right aircraft. It has 64 seats, the economics work out that this can support business class fares, more like $5,000, making it economically compatible with more routes.

AEROSPACE: What about military variants? You’ve proposed Overture as a supersonic Air Force One.

Could we see a supersonic Air Force One?

SCHOLL: We really zeroed in on what we want to do there and we did some great work with DoD and some great work with Northrop to understand where the aircraft is useful and where it’s not. It’s not a good ISR aircraft and it would make a terrible tanker but it’s really good at moving people and things. The most obvious use case is as an ultra VIP transport. In the US today we have some rusty old 757s that carry around the First Lady, Cabinet members and congressional delegations. Sometimes they even carry around the president – but they go Mach .75, and they’re really old so they are expensive to maintain. Today’s Air Force One (AF1) is a 747 and Overture is obviously much smaller – but for the price of one converted 747 the US government could get ten Overtures. That large aeroplane has to be basically a flying tank, it needs missile defences, countermeasures and who knows what else. However, the reason all of this is needed is because anybody watching knows exactly where the president is – but when the president travels on the ground, he doesn’t travel in a tank; he travels in a motorcade. So why don’t we do the same thing in the air? What if there were five Overtures and the bad guys don’t know which one POTUS is in? If you think of it that way, it could be far safer and more pragmatic to build several AF1s.

AEROSPACE: What about the environmental impact of supersonic flight?

SCHOLL: We’re forward compatible with sustainable aviation fuel, so when there is enough available we’ll be able to run on 100% SAF. However, I think the way the world thinks about CO2 is often wrong. There is only one atmosphere, and it’s all mixed together – yet we go after every source individually. For example, right now aviation contributes around 2.5% of global CO2 and supersonic aviation will start off being a tiny portion of that. On the other hand, the impact from forest fires is about ten times bigger than aviation, we should figure out how to fix those – we’re not thinking holistically about the problem.

AEROSPACE: How serious do you think China is about supersonic airliners?

SCHOLL: They’re really serious. The way to tell is they gave it a product number, C949. The release that was put out is obviously a cartoon and anybody who knows anything about supersonic aircraft knows that one won’t work. But I don’t think it is the actual aircraft. They haven’t figured it out yet. We’re ahead, and if we can stay out of our own way and go fast, we’ll win the race.

AEROSPACE: You revealed the Overture flightdeck last year at the Farnborough – was there any changes or feedback from Concorde pilots and other pilots who trialled it?

SCHOLL: People already love it but, but we can make it so much better. One of my beliefs is that to get the best product, whether we’re talking an engine, flight deck or passenger cabin, requires constant iteration. I found all kinds of things people didn’t love, like the throttle handles which are too big for those with small hands. Meanwhile the Airbus pilots are: ‘where’s the where’s the tray table for my food’? There are many other little details that are not quite dialled in yet, so the final design will lock as late as possible.

I know pilots would love to hand fly this thing, but in the boomless cruise mode in particular you really need the real time weather data feeding the autopilot – so it will be an autopilot selection. It will then pick the fastest quiet speed for the cruising altitude and if there is a better altitude or heading give recommendations to the pilot.

AEROSPACE: What are Boom’s next milestones?

SCHOLL: We are in the process of modifying the engine test facility out in Colorado for Symphony testing and in the first part of the manufacturing process for the prototype core. The first turbine blades came out of the 3D printer in March. Every day I’m approving a purchase order for engine parts and the assembly will start in September or October. The goal is to make ground runs by the end of the year, it’ll be tight, but it’s getting done. Then next year, we’ll do a full-up turbofan. In parallel, we’ve reached firm configuration on Overture, and we’re in the process of refining that now, doing the systems and detailed engineering. Later this year we’ll release the final outer mould line and then that will support the development of the next part. It won’t be long before one of these things will be rolling out.

AEROSPACE: What is going to happen to XB-1 now?

XB-1 ‘Baby Boom’ was a success, but its mission is now complete.

SCHOLL: It is going come back to Denver to sit in our new R&D building. The most awesome thing we’ve built will be in our lobby, and it will inspire the men and women who are working really hard to create everything else. I want them to walk in every day, see it, and remember what this company can do if we work hard and smart, Once we have something better than XB-1, then we’ll let XB-1 go to a museum. I think inspiration really matters. I don’t want to walk into an office building, I want to walk in and see what we’ve done and be inspired by that.