The China-US trade ceasefire broken down

A recent Reuters article broke down the essence of the trade ceasefire agreement between the US and China as following:

1. Tariff reduction on Fentanyl related Chinese goods

The US will halve the 20% tariff on Chinese goods related to supplies of fentanyl opioid precursor chemicals coming from China. The reduction to 10% on the duties first imposed in February will cut the overall US tariff rate on Chinese imports to about 47% from 57%, according to US officials.

That total includes duties of approximately 25% imposed on Chinese imports during Trump’s first term in the White House, a reduced 10% “reciprocal” tariff imposed in April, and previous “Most Favoured Nation” tariff rates.

2. Pause on China’s rare earth export controls

China agreed to a one-year pause on export controls after introducing an export ban on rare earth minerals and magnets earlier this year. Rare earth minerals play a vital role in the production of cars, planes, and weapons, and have become Beijing’s most potent and powerful leverage in its trade war with Washington. Those controls would have required export licenses for products with even trace amounts of a larger list of elements and were aimed at preventing use in military products.

The White House stated that China will also issue general licenses for the export of rare earths, gallium, germanium, antimony, and graphite, benefiting US end-users and their suppliers. The White House said that amounted to “the de facto removal of controls China imposed in April 2025 and October 2022.”

China also agreed to suspend all retaliatory tariffs it has announced since March 4, including duties on US chicken, wheat, corn, cotton, sorghum, soybeans, pork, beef, aquatic products, fruits, vegetables, and dairy products.

3. The Trump administration’s Export controls paused

The US agreed to a one-year pause on an expanded Commerce Department blacklist of companies prohibited from buying US technology goods, including semiconductor manufacturing equipment, a move aimed at averting the use of subsidiaries and other firms to bypass export controls.

The expanded blacklist would have automatically included firms more than 50% owned by companies already on the list and would have had the biggest impact on Chinese companies, banning US exports to thousands more Chinese firms.

4. China commits to soybean purchase

The White House stated that China agreed to purchase at least 12 million metric tons of US soybeans in the last two months of 2025, and at least 25 million metric tons of US soybeans in each of the following three years, as well as to resume purchases of US sorghum and hardwood logs.

5. Trump administration pauses new port fees

Beijing agreed to remove measures it had taken in retaliation for Washington’s Section 301 investigation of China’s dominance in the global maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sectors, and to remove sanctions imposed on various shipping entities.

The Trump administration agreed to a one-year pause for the new port fees imposed on Chinese-built, owned, and flagged ships. The fees, aimed at reviving US commercial shipbuilding, could have added millions of dollars to the cost of each voyage to US ports, with shipping lines, freight forwarders and shippers breathing a loud sigh of relief after the announcement was published.

The port fees took effect on October 14, along with 100% tariffs on Chinese-built ship-to-shore cranes. They quickly disrupted cargo flows, pushing up container rates as shippers sought to avoid China-linked vessels. China has imposed its own fees on US-linked ships, including those from global shippers with 25% US ownership.

The White House stated that it would negotiate with China on the issue in the meantime, while continuing talks with South Korea and Japan on revitalising American shipbuilding.

6. Cooperation on fentanyl trafficking

China agreed to take “significant measures” to end the flow of fentanyl to the US, including moves to halt the shipment of certain precursor chemicals to North America and strictly control exports of other chemicals worldwide.

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent told Fox Business Network this week that working groups from the two countries would “set very objective measures” in the coming weeks on reducing flows to measure success in curbing the deadly opioid blamed for tens of thousands of US overdose deaths every year.

When Trump first imposed the fentanyl-related tariffs, officials in his administration said they were wary of ongoing promises by China to help, and that the tariffs would remain in place until Beijing had taken concrete measures. [3]

Global trade reconfiguration gives birth to the US+1 mega-trend

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic, the term “China+1” became the hot supply chain take on ensuring a decreased reliance on China as the predominant production and assembly factory of the world.

10 months after the Trump administration took office, it is now clear that the persistent use of tariffs as a geopolitical and trade tool has given birth to an emerging US+1 trend across the world.

As no surprise, China is leading the way in terms of further diversifying its exports to ensure a lesser reliance on the US, recording a decrease in its exports of a whopping -16.9 % during the first nine months of 2025. This trend is even more remarkable given that China recorded a total export growth of 7.1%, proving the resilience of China’s exports.

Source: Reuters

It will naturally be a “forever” discussion whether it is in fact China succeeding in easing reliance on US exports, or whether it is in fact US importers seeking a safe tariff harbour and diversifying imports further. However, with an estimated US economic growth of only 1.8 % in October, economic indicators support the notion that China has gotten the long end of the trade-war stick so far.

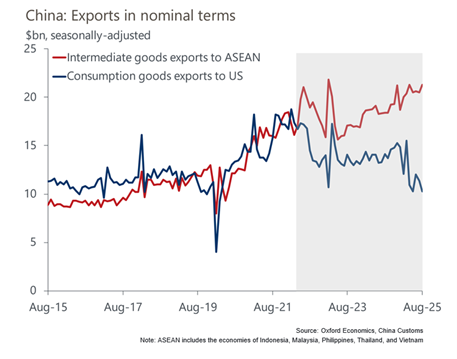

The Chinese method has been simple yet effective, and in essence, can be explained as diversifying from developed to emerging markets. It can be fairly argued that this development has been ongoing for years; however, it is clear that the recent trade war has accelerated this development. A recent report from Oxford Economics untangled this effect further, noting that China in recent years has steadily increased exports to ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), Latin American and African countries with especially exports to ASEAN countries driving the growth. [4]

Source: Oxford Economics

The timing of this trend is no coincidence, with China reacting immediately to the first round of the US trade war during Trump’s first period in office.

In particular exports of vehicles, communication equipment, and electrical machinery to emerging markets, such as those in ASEAN and Latin America, have risen sharply due to both supply chain diversification and rising local demand for China’s electric vehicles.

The US and Northeast Asia still represent about 32% of China’s total export value (versus 45% in 2017), but their dominance is rapidly fading. This year’s tariff increases have reinforced these redirections. Since February, export growth to ASEAN, India, Africa, and Latin America has been nearly double the pace of contraction in direct shipments to the US, suggesting and confirming that new trade links are gaining traction faster than older ones are eroding.

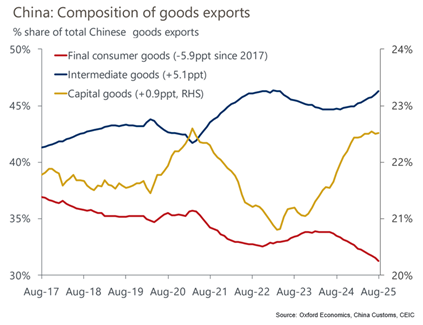

China pivots away from “Final Consumer Goods Production” label

Breaking the trend further down, it is also clear that while China still holds the title as the “Factory of the World”, it is steadily increasing its exports of intermediate and capital goods. China has been widely recognised as a “final assembler” economy; however, Chinese manufacturers are shifting towards being a key supplier of intermediate products.

Source: Oxford Economics

Since the mid-2010s, other economies have become increasingly reliant on Chinese-made inputs, especially in green industries such as solar and EV mobility.

The implications of China’s multi-year pivot from final consumer goods to capital and intermediate goods means that it is increasingly difficult for global manufacturers to exclude Chinese components and thereby reduce reliance on China. An increased presence in upstream production also makes demand for Chinese exports relatively insulated to tariff shifts.

What the does 2026 crystal ball hold following the US and China trade ceasefire

While lessons learned so far in 2025 indicate that we cannot count on any agreement being definitive, it is likely that there will be a widespread positive effect from the trade war ceasefire. Shippers around the world and not least in the US need a form of stability if the US economy is to kick back into gear.

Neither China, nor US seem to have appetite on an intensified and prolonged trade war and our assessment is that the current status quo, very likely will be the long-term solution. The threat from China of restricting US access to rare earth minerals is so profound and impactful that the US administration has no upside in increasing trade tensions, and conversely China needs a steady and strong export to the largest consuming country in the world.

Accordingly, we also expect a healthy uptick in demand during Q1 much to the relief of both ocean carriers and airlines which you can read more about further down.

The Hamas-Israel ceasefire is a fragile peace with continuous tensions

The ceasefire between Israel and Hamas holds, but the situation remains fragile. Despite diplomatic progress, logistical challenges and security concerns continue to delay the full return of hostages’ remains and the delivery of humanitarian aid.

While Israel and Hamas are committed to the ceasefire terms, including the return of bodies, hostages and the facilitation of aid, the recovery efforts face significant delays due to destroyed infrastructure and ongoing restrictions. Humanitarian organisations report that aid deliveries are still insufficient to meet Gaza’s needs, with key facilities struggling to operate due to limited access.

Reports say that both sides are under pressure to fully comply with the terms of the ceasefire, but with the ongoing internal instability in Gaza and limited progress in easing the humanitarian crisis, the ceasefire remains fragile.

The Houthis have stated that they will refrain from targeting any vessels while the ceasefire holds. However, carriers show no immediate signs of resuming routing through the Red Sea, citing continued concerns about the longevity of the ceasefire. Operationally, it would be very disruptive for ocean carriers to resume Red-Sea routing and then have to change back again later.

We anticipate that, while the ceasefire is long-awaited positive news not only for the people in Gaza and Israel, but also for the broader shipping industry, shipping lines are expected to maintain Cape of Good Hope diversions for at least the next 6 months and well into 2026.

IMO Net Zero Framework vote postponed for a year

As the IMO continues its efforts toward a global climate framework for the shipping sector, the deal is now facing mounting political resistance. While there was initial momentum in favour of the proposal, growing pressure from the US and Saudi Arabia had intensified ahead of the October meeting in London. Both nations lead the push to block the agreement.

Prior to the meeting, Trump made his opposition clear, denouncing the proposed global CO2 levy on shipping as a “fraud tax” and declaring that the US would not comply. In the run-up to the vote, the US administration threatened sanctions, tariffs, port levies, and visa restrictions against countries that supported the deal. This stance had prompted the US to join forces with Saudi Arabia and other oil-producing nations seeking to convince member states to reject or abstain from the vote. “It’s like dealing with the mafia,” a source described as a veteran of IMO negotiations told the Financial Times. “It’s bully tactics. They don’t need to tell you exactly what they’re going to do to you, just make it clear that there will be consequences.” [5]

On 17 October, the IMO announced that members had voted to postpone the Net Zero Framework vote for another year – effectively leaving the initiative in limbo, and supporters of the deal left the meeting disappointed and frustrated. Concluding the conference, the IMO Chairman Harry T Conway stated: ”Delegates, we meet in one year’s time. There is no other business to be discussed.” [6]

The outcome marks a clear setback of the industry’s climate ambitions and, in the short term, a missed opportunity to implement uniform global regulation – “a precondition to securing a level playing field in a global industry,” as Maersk noted in its statement. [7]

While few container shipping lines have commented on the decision publicly, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) voiced frustration that the states failed to agree on a path forward, stressing that the industry needs clarity to make long-term investment decisions. Hapag-Lloyd reaffirmed its own decarbonisation targets but warned that the already limited supply of green fuel may be negatively impacted by the decision.

While only a few container shipping lines have commented on the decision publicly, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) voiced frustration that the states failed to agree on a path forward, stressing that the industry needs clarity to make long-term investment decisions. Hapag-Lloyd reaffirmed its own decarbonisation targets but warned that the already limited supply of green fuel may be negatively impacted by the decision.