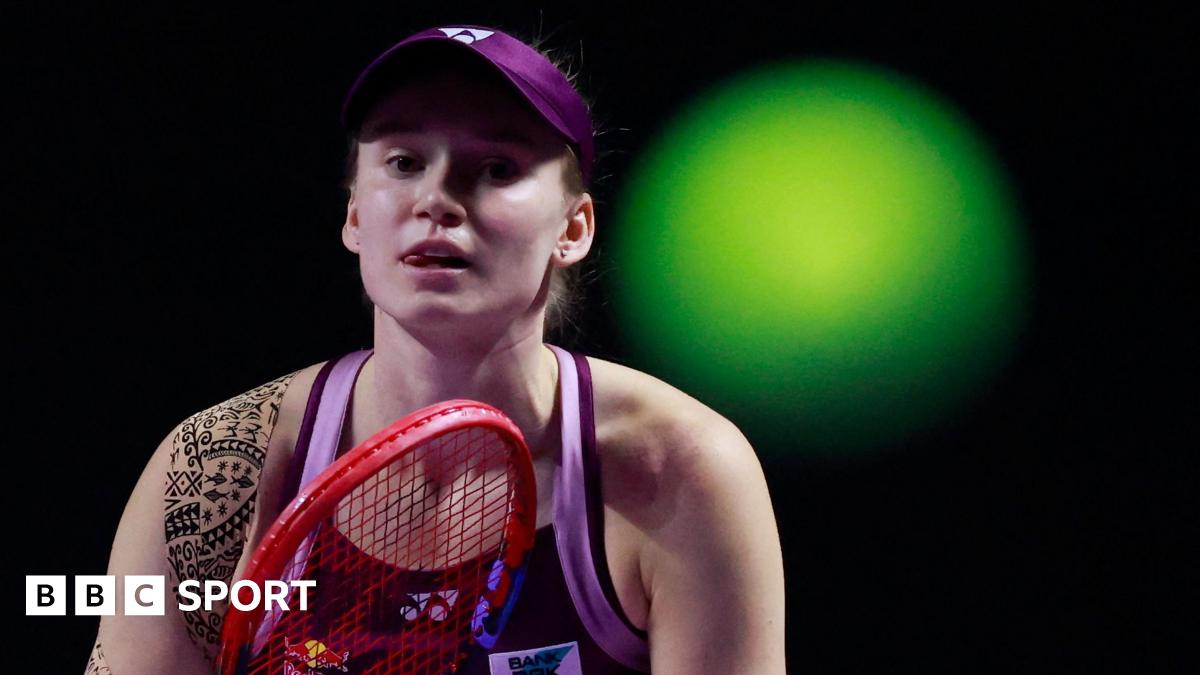

Elena Rybakina completed a clean sweep of her group at the WTA Finals with a straightforward victory over late call-up Ekaterina Alexandrova.

The sixth seed, who sealed her progression to the semi-finals on Monday, continued her momentum with a…

Elena Rybakina completed a clean sweep of her group at the WTA Finals with a straightforward victory over late call-up Ekaterina Alexandrova.

The sixth seed, who sealed her progression to the semi-finals on Monday, continued her momentum with a…