On November 29, 1972, a fire broke out in the high-rise Rault Center, in downtown New Orleans. As firefighters struggled to reach the blaze and television cameras rolled, five women trapped in a beauty salon on the 15th floor had to make an impossible decision: remain in the burning building, or leap.

One by one, they jumped, aiming for the roof of a neighbouring six-storey building. Four of the women died.

At the time, a 46-year-old engineer and fellow New Orleanian had been toying with an idea that might have saved them. The tragedy spurred John T Scurlock into action.

He wanted to engineer an inflatable cushion that could provide a safe landing for people plunging from great heights. But to do it, he needed the help of his sons.

First, he got them to push 45kg (100-pound) rolled-up pieces of vinyl off the top of his office building and onto the cushion he had designed below. The vinyl was attached to an accelerometer, which helped John calculate the weight the cushion could absorb at different speeds.

Once he was confident it was safe, it was time for the next step: having his sons jump off the roof.

“We were like 10, 12, 14 years old, and we were jumping off a building into a big airbag. It was a lot of fun,” recalls Jeff Scurlock, now 66.

‘Space pillow’

The following year, John patented the safety air cushion, the huge, inflatable pad still used today by fire brigades from New York to Tokyo to rescue people from fires and deaths by suicide.

But it was not his first invention. In fact, his life-saving inflatable was drawn from his earlier invention: the ubiquitous fair attraction known by many different names – the bouncy castle, moon bounce, bounce house or space walk, depending on where you are bouncing.

In the Scurlock home, it was known as the “space pillow”.

A year after John filed a patent for the core of what would become the space pillow, he started working at a NASA facility in New Orleans. It was 1961, and NASA had opened its doors three years earlier in response to the Soviets pulling ahead in the space race with the launch of the world’s first satellite, Sputnik 1.

The US space agency was abuzz with projects exploring the possibility of spaceflight, and by 1960, it had developed an interest in designing a crewed, inflatable space station, thought by many to be a necessary first step in reaching the moon.

Large, rigid space stations would require multiple rocket trips to bring up the parts, but plastic inflatables were considered light, strong and easy to transport. An inflatable space station could be launched into space with a single booster and unfurl once in orbit. (A meteorite-resistant inflatable space module was sent up to the International Space Station in 2016, and NASA engineers are hoping to build a semi-permanent moon habitat out of inflatables.)

John found himself in the middle of this innovation, which continued even in his spare time, when he would sketch designs for and stitch his proto-space pillow, using a commercial sewing machine he set up in a pit in the ground of his garage so he could haul the heavy vinyl material towards him as he stitched.

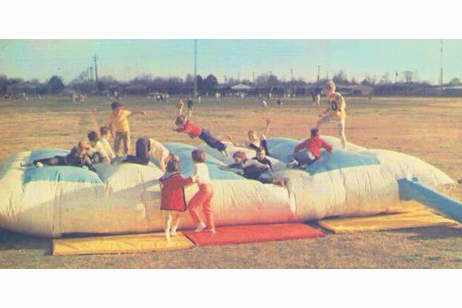

When he assembled an early, homemade space pillow for his young sons to play with in the backyard, it soon became a massive hit with the local children.

“We were very popular kids then, because we had one permanently in our backyard,” says Jeff. “The whole neighbourhood would come and jump on it.”

Jeff says it was his mother, Francis, who recognised how much children loved the inflatable and got the idea to market it. Eventually, John left his job to concentrate full-time on the “space pillow”.

Inflatable solutions

In 1968, they started selling the invention to fairs around the country. But the safety risks were serious. “It was a nightmare, safety-wise,” says John’s grandson, Mials, 35. “It had no support, no netting, no way to keep you on it.”

When a carnival worker broke his neck and died, the company was “sued out of existence”, Mials says.

No longer a small backyard venture, the design needed protective features.

John set to work designing improvements: the space pillow grew columns, cushioning walls, netting around the sides and a roof, making it far safer. In 1972, the last year man walked on the moon, the family launched a new company, called Space Walk Inflatables, to manufacture and rent inflatables in the Louisiana city of Kenner.

Today, the global bounce house market is worth $4bn, driven by the popularity of rentals.

But as his invention ballooned in popularity, John also turned his attention to solving problems with heavy-duty inflatables.

Inflatable engineering is deceptively complex and requires answering mathematical questions to turn a 2D fabric into a 3D shape, says Dr Benjamin Gorissen, a professor of inflatable mechanics at KE Leuven in Belgium.

John loved numbers, recalls Mials, and was “a guy who could do the math”. He filed patents on several structures, including one intended for underwater pipe welding for offshore oil platforms, which resembles a human heart with someone working inside.

“Whatever news article would happen, he’d be in his office, sketching out a solution,” says Mials.

Jeff recalls his father reading about sunken submarines in the newspaper, and then working on an invention that could help to resurface them.

Up until John’s death in 2008, “he never really stopped working”, says Jeff. His last creation in his 80s was a giant inflatable palm tree, a kind of air sculpture meant to provide shade over a 2.8 square metre (30sq ft) area.

John did not set out to build a business empire, Jeff and Mials, who now run the business, note. Though bouncy castles remain the core of their business, the Scurlocks continue to produce safety air cushions, which have a more complex structure. Their most heavy-duty product is certified for 20 storeys, or 200 feet (60m).

Since it was invented, the safety air cushion has saved thousands of lives around the world, but it all began with an early, devoted pioneer urging his children to jump off the roof.

This article is part of ‘Ordinary items, extraordinary stories’, a series about the surprising stories behind well-known items.