BBC

BBCIt was 17 August 2000 and a group of people were huddled around a computer screen in the BBC TV newsroom, when suddenly there came a collective gasp. One of the group turned around and announced, very solemnly: “Nasty Nick’s gone.”

Nick Bateman – a housemate in the UK reality TV show Big Brother – was found to have attempted to “manipulate” his fellow contestant’s votes, and was asked to leave the reality TV house. It would become front-page news.

The saga prompted a nationwide moral debate, not only about the incident but the very existence of the show.

Writing for the London Evening Standard one TV critic accused Big Brother’s top executive Peter Bazalgette of “smearing excrement over our screens”.

A reviewer from The Herald newspaper denounced the housemates as “fakers, chancers, dullards, no-marks, and dimwits”.

Yet Britons voted with their feet (or their remote controls). Some 10 million people tuned in for the finale on 15 September – marking the start of a major cultural shift.

Press Association

Press AssociationNow, 25 years on, reality TV is one of the most popular genres on screens in the UK.

The Traitors attracted more than 10 million viewers for the opening episode of third series in January. And Love Island UK may have seen audiences shrink since its episode peak of six million in 2019, but it has still been renewed 10 times.

For years, the dark sides of reality TV have been unpicked. There have been concerning, in some cases devastating, impacts on the contestants of certain shows, which has rightly prompted change.

As for critics, some have continued to dismiss many reality TV shows as superficial escapism, at best – or, at worst, harmfully divisive.

Listen closely, however, and a small clutch of psychologists and social experts are quietly starting to tell a different story – one that suggests that the impact of watching reality TV might not be as bad for brains (or social consciences) as it may seem.

Getty Images/ Press Association

Getty Images/ Press AssociationSome suggest that it could help viewers build a better grasp of perspectives outside our realm of experience, or even overcome biases.

“Reality TV has historically been more diverse demographically than other forms of media,” says Danielle Lindemann, a sociology professor at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania.

“[It] casts a spotlight over patches of the social landscape that we don’t always see, so in that way, it can be a tool for greater social understanding.”

A glimpse behind the curtain

The UK Big Brother, based on a Dutch television series of the same name, brought together a group of 10 strangers in a house in London.

For 64 days, contestants were sealed off from the outside world and their every move filmed, with viewers voting out roughly one person each week until a winner was handed the £70,000 prize.

What was truly innovative wasn’t the competition format but the connection between the audiences and the ordinary people whose lives inside the house played out on screen.

“That didn’t exist before,” says Dr Jacob Johanssen, associate professor of communications at St Mary’s University, who researches the psychological effects of reality TV.

“For the first time, viewers started seeing ordinary people on television who weren’t celebrities, which is a very different phenomenon.”

ITV/PA Wire

ITV/PA WireToday reality TV covers a broad spectrum — from fly-on-the-wall dramas that document the lives of friends (The Only Way is Essex, Geordie Shore, Made in Chelsea) to competition-based shows (Survivor, The Traitors, Love Island) that revolve around the ‘reality’ of contestants’ lives.

But its power remains the same – each offers a glimpse into the dramas of real peoples’ lives – a chance to see behind the curtain.

“You do see lots of unfiltered, raw emotions… in these different programmes,” continues Dr Johanssen. “If we see them in real life, usually that would happen in the private sphere, certainly not in public.”

‘People feel less isolated or alienated’

Dr Johanssen has worked on the reality show Embarrassing Bodies, which features patients consulting with doctors, aiming to destigmatise common health complaints.

As he sees it, “even though there are lots of problematic aspects to it, it made people aware there are different kinds of body types, there are different conditions people might have.

“It perhaps made people feel less isolated or alienated.”

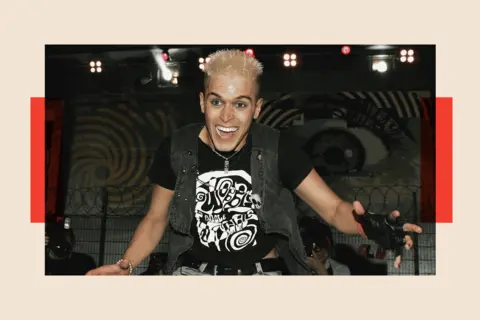

The same can go for disability awareness. Pete Bennett, the winner of the 2006 series of Big Brother, was a livewire personality who won over the public, also happened to have Tourette’s syndrome.

His appearance on the show felt groundbreaking at a time when disability awareness and representation in the UK was nowhere near current understanding – and it gave enough screen time for a mass audience to both be introduced to Tourette’s, but also warm to Pete.

“I’d get bullied a lot with Tourette’s,” Pete explained of his time before Big Brother. “I couldn’t really go out and enjoy myself without being ridiculed or started on because of my ticks.”

But he adds: “I’ve never been bullied since leaving the house.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThen there are the conversations about uncomfortable, and sometimes controversial, subjects that contestants have delved into too – in some cases a lightning rod for national discussions.

Over the years, several Love Island contestants have been accused of “gaslighting,” a potential form of coercive control, which is a criminal offence. It has prompted much discussion on social media, in one instance leading Women’s Aid to release a statement.

Prof Helen Wood of Lancaster University, who researches and advises on the ethics and practices of reality TV, recalls a separate discussion about domestic abuse and argues that raising this can be a positive.

“I remember a big debate about Love Island and whether it allows… a conversation on what domestic abuse looks like?” she says. “For some audiences that could be triggering, for some audiences that could be helpful.”

Insights into social cues… and deception

Faye Winter was 26 when she appeared on Love Island. She worked as a lettings manager at the time, but lamented there were, as she saw it, “no fit men in Devon”, where she lived, so she applied for the show and joined the 2021 series.

Quickly, she partnered up with Teddy Soares, a financial consultant originally from Manchester.

“From a girl’s standpoint, they’re going to have to get used to me stirring a few pots and causing a bit of a ruckus,” he told ITV after signing up.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe promised ruckus soon materialised, after Faye was shown a clip in which Teddy admitted to being sexually attracted to another contestant.

Her heated, expletive-filled shouts, in which she called Teddy two-faced, prompted almost 25,000 complaints to Ofcom.

Some considered her response disrespectful and an “overreaction”. Yet other viewers strongly identified with her.

“I got a lot of trolling for it,” she later told a newspaper. “[But] I got a lot of people who said they’ve been through it”.

Dr Rosie Jahng, an associate professor of communications from Wayne State University in Michigan, believes that the insights offered by reality TV into social cues, body language, and deception, can be valuable.

“It becomes like testing a moral boundary – we start to ask, ‘what would I do in that situation?’”

When reality TV becomes ‘constructed’ reality

Understanding how others react in situations can in itself be informative, or prompt self-reflection. But what happens when reality TV deviates away from documented reality to a murkier type of “constructed” reality?

A former Made in Chelsea cast member previously explained how it worked when she was on the show.

“The producers spoke to us on the phone for hours every week,” Francesca “Cheska” Hull, who appeared from the first series, previous said in an interview.

“They’d come on nights out with us. They put us in situations that created drama.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe stressed that scripts weren’t used but added, “You knew the conversations you had to have”.

On the surface, at least, this seems to deviate from the idea of following raw emotions. But psychologists have suggested that even constructed reality can have benefits.

“It can potentially offer benefits to viewers and society because it can lead to wider conversations about the world we want to live in,” argues Dr Johanssen. “For instance when it comes to problematic or unethical behaviour or questions of gender identity and inequality for example.”

The darker side of reality TV

The experiences of people who appear on the shows, however, raises an entirely different set of questions.

“We have to separate out the value of a show sparking a conversation and what’s happening to participants,” explains Prof Wood. “A lot of shows, especially early shows, were about putting people in very difficult situations that were trauma-inducing.”

During the 2007 series of Celebrity Big Brother, actress Shilpa Shetty found herself at the centre of a race and bullying row, after a fellow contestant called her “Shilpa poppadum”.

The incident sparked a national conversation about racism.

Press Association

Press Association“With the Shilpa Shetty case… there were lots of complaints where people felt someone was being bullied or not being treated well on screen,” says Prof Wood.

“I think that moment enabled a sort of shift. We don’t want to see that anymore.”

More recently, some Love Island contestants have spoken about their experiences of poor mental health following the show, as well as struggles with the relentless scrutiny.

A UK parliamentary committee carried out an inquiry into reality TV in 2019, and said its “decision to launch the inquiry into reality TV comes after the death of a guest following filming for The Jeremy Kyle Show and the deaths of two former contestants in the reality dating show Love Island”.

PA Media

PA Media“We’re still not there in terms of whether participants are completely adequately cared for,” argues Dr Johanssen, who submitted evidence to the inquiry.

“They have no agency or control over the edit, or what an episode looks like, how somebody is portrayed.”

However, Love Island’s producers have said they’ve learned how to better support the cast and crew. Revised welfare measures have been introduced including specialised social media training for contestants, as well as video training and guidance on topics including coercive behaviour and avoiding discriminatory language.

Ofcom also established new rules to protect those appearing on TV and radio reality shows, following a steady rise in complaints over the welfare of guests — saying broadcasters must “properly look after” contributors, particularly those who might be at risk of “significant harm” as a result of taking part.

“A lot of the broadcasters are saying to us that there’s a shift in mood,” adds Prof Wood, who is working on a research project looking at care practices in UK reality TV.

“They want participants… to get something better out of it than they would have in the past.”

Reflecting society back at itself – or shaping it?

The question that remains, however, is what the collective impact is. Is reality TV just holding up a mirror to society, or could it really play an active part in shaping it?

Prof Lindemann believes that there are examples of positive connections between the material on reality shows and how viewers engage with the world.

Even as far back as 2011, it was found to be having an effect on behaviour.

Press Association

Press AssociationShe points to one US study which found that girls who watched dating shows like Temptation Island, The Bachelor, or Joe Millionaire were more likely to talk with one another about sex.

In 2014, a paper was published, cowritten Melissa Kearney an associate professor of economics at the University of Maryland, that drew links between a reduction in teenage birth rates in the US, and the airing of a reality series on MTV called 16 and Pregnant, which offered a brutally honest look at life for pregnant teenagers.

This show “was not specifically designed as an anti-teen childbearing campaign,” wrote the authors, “but it seems to have had that effect by showing that being a pregnant teen and a new mother is hard.”

They concluded: “We find that media has the potential to be a powerful driver of social outcomes.”

One decade on, that certainly hasn’t changed. Which makes reality television a powerful tool. In some cases that tool is powerful for the worse – but just sometimes, it really could shape those watching it for the better.

Top picture credit: ITV/PA Wire

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.