We wouldn’t have gotten Windows 7 if it wasn’t for Windows Vista, and we wouldn’t have gotten Windows 10 if it wasn’t for Windows 8. Windows 10 was first released on July 29, 2015, making it 10 years old, and support ends this year.

The OS will be fondly remembered, for a number of reasons. For one thing, it was the first time Windows was offered as a free upgrade, so that’ll do it. It was also sandwiched between Windows 8, which very few people liked, and Windows 11, which forced increased system requirements for the first time in over a decade.

Windows 10 was a massive success from the perspective of overall adoption and usage. For everything else, it was a spectacular failure. Almost everything that was promised either never shipped, was discontinued, or is currently on the back burner. And it will go down as a monumental achievement for Microsoft.

Recovering from the Windows 8 disaster

There was a lot that needed to be done

The story of Windows 8 is a fascinating one. Apple had released the iPhone in 2007 and the iPad in 2010, and for the first time, consumers were choosing between a laptop and something that wasn’t a computer (we can do the ‘What’s a computer’ thing another time). Prior to that, the cheap alternative to a laptop was a netbook, and now, the industry was being truly disrupted.

The disruption was multifaceted. The iPad had multitouch, yes, and that’s the thing most people focus on as we head into the Windows 8 era. But it also had 10 hours of battery life thanks to its Arm chipset. Moreover, Apple had the App Store, a centralized place to get software that wouldn’t damage your device, while Windows has the wild west of the internet and viruses.

Microsoft set out to reimagine Windows, and all of this led to Windows RT and Windows 8. Windows RT was meant to be what Windows on Arm is today, without the emulated Intel apps. Microsoft genuinely thought app developers were going to remake their apps for what was then called the Windows Store, and in fact, it thought you’d spend most of your time in the metro environment, with the desktop only accessible when you need it.

The Windows 8 desktop, without a Start button

All of this flopped, of course. Microsoft released two generations of the Surface RT, and third-party OEMs quickly scrapped their own Arm tablets. Windows 8, left to desktop users, was a mess. The Start Menu was the Start Screen with giant tiles, some apps had to be controlled with gestures instead of the standard close buttons we’ve seen for decades, and more.

Related

The Surface RT was actually good – Windows RT was what went wrong

Looking back at the decade-old Surface RT, it was actually pretty good. The Windows RT OS, on the other hand, was awful.

Windows 10 set out to fix all of this. The biggest change in the first Technical Preview was that it brought back a Start Menu. Even Windows RT devices, which never got the Windows 10 update, got a special Windows RT 8.1 update with a Start Menu.

The dual metro and desktop environments were gone, as was the dual Internet Explorer browsers. In fact, Internet Explorer was placed in the background in favor of the new Edge browser, originally codenamed Project Spartan.

Store apps could live in windows now, rather than the default full-screen experience, and rather than making a UX that assumed everyone was living on a tablet, the shell automatically adapted if you removed a keyboard from your Surface or folded the display back on your convertible.

And also, a whole lot of promises were made…and broken.

A free upgrade for all

Every Windows 7 and Windows 8.1 user was (and still is) eligible

Windows XP was first released in 2001, but support didn’t end until 2014, bucking the trend of 10 years of life. The date kept getting pushed back. Sure, part of the reason was because new versions had entered the market for things like netbooks, but really, the problem was that too many people were still using Windows XP after a decade.

It was the first version of Windows for consumers that used the NT kernel, and it was the first time consumers were really asking themselves what the value was in buying a whole new PC. Even though Windows 7 was a huge success, XP just wouldn’t go away.

Microsoft’s biggest competitor was itself. It was constantly trying to sell people new products, and the people it wanted to buy them weren’t using products from competitors; they were using older Microsoft products.

This, of course, caused fragmentation, and it introduced a revolutionary new concept. Windows 10 was going to be a free upgrade for anyone running Windows 7, Windows 8.1 (it wasn’t technically available for Windows 8, but Windows 8.1 was a free upgrade for those users), or Windows Phone 8.1.

The system requirements didn’t change either. Every single Windows 7 and 8.1 PC, with an extreme minority that had compatibility issues, could get Windows 10. In fact, Windows 7 hadn’t even increased system requirements from the recommended requirements for Windows Vista.

The goal was to get Windows 10 on over a billion devices within two to three years, something that ultimately took about five years. Those billion devices wouldn’t just be PCs either; it included phones, VR and AR glasses, IOT devices, and more.

To stop competing with itself, Microsoft quite literally gave away the upgrade. You still had to buy a new copy of Windows if you were building a PC, although you could always catch Windows 7 and Windows 8.1 licenses on discounts and use those. The free upgrade was promised to be for a year, but it was never turned off.

The last version of Windows

Windows is a service now

While not actually running Windows 10, Microsoft Band was part of the hardware ecosystem that Microsoft built out

Most people I talk to will point out that Microsoft said Windows 10 was going to be the last version of Windows, but it never actually said that, at least publicly. In the run up to the release, a developer evangelist that worked at Microsoft named Jerry Nixon said that, and Microsoft just never said it was false.

What Microsoft did say was that Windows is a service now, something that sparked endless conspiracy theories about a plan to turn this free upgrade into a paid subscription service, much like Office 365. Yes, the theory was that it was a bait and switch. Microsoft pushes you to upgrade for free, and then starts charging you to continue using your own computer. Those theories were dumb, but they weren’t incredibly rare among enthusiasts on the internet.

The idea behind Windows as a service was that instead of releasing a big new version every 3-ish years, you’d get regular feature updates. These were originally planned for twice a year, and eventually became annual. Microsoft was promising to take more ownership over the lifecycle.

There were a bunch of growing pains. The company constantly had to tweak just how hard it pushed you to install a feature update, and how long it would allow you to hold off. In late 2017, it skipped the preview period to release version 1709 and some people had their files deleted.

There was also a lot more community involvement, which started in September 2014 with the introduction of the Windows Insider Program. Essentially, instead of having internal testers, Microsoft offered Windows 10 testing to anyone that wanted it, and let you file bugs and feature requests in an app that came pre-installed.

This servicing model is still what we see today. Whether the internal plan was for Windows 10 to be the last version or not, I’ve heard mixed stories from folks on the Windows team. Remember, at the time, macOS was still OS X, so it wasn’t crazy to think that it was possible to push feature updates while still keeping the ’10’. The team could have shipped an entirely new shell and just called it a new version of Windows 10.

However, one thing we know, and we know Microsoft knows, is that there’s a huge spike in interest and PC sales with a new version of Windows. Branding matters.

Now, interestingly, the statement about it being the last version of Windows might not have only been true at the time, but it could be true now. Windows 11 is still Windows 10 under the hood. The build number for the most current version of Windows 11, 24H2, is 10.0.26100. While visual and branding changes have been made, Microsoft still hasn’t moved on from Windows 10.

One Windows platform for everything

And the introduction of the Universal Windows Platform (UWP)

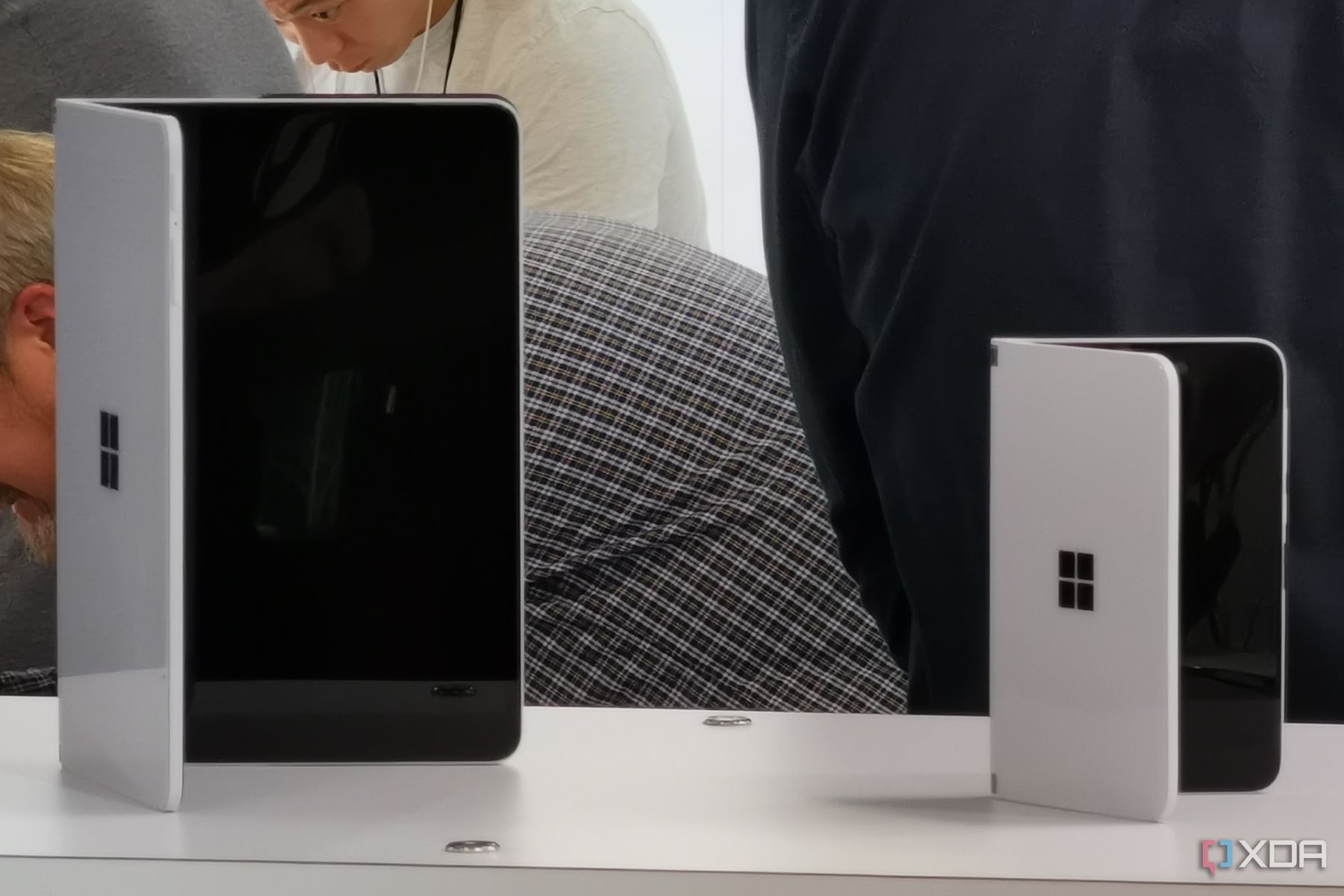

The Surface Neo was going to be a dual-screen device running the new Windows 10X. Both the OS and the device were scrapped.

Today, you probably think of Windows 10 the same way you think of any other version of Windows. It’s a desktop operating system that you use to get to the apps you want to run.

It was originally supposed to be much more than that. As we all remember, Microsoft used to make a platform for phones too, and Windows Phone 8.1 was going to be upgraded to Windows 10 Mobile.

Ahead of Windows 10’s launch, it also announced HoloLens, running a version of the OS called Windows Holographic. Indeed, if you look back at the early demos, it offered a lot of the same experiences that Apple is touting from its Vision Pro today. I tried it, and it was awesome.

Windows 10 was coming to IOT devices too, such as the GLAS Thermostat. It was going to be everywhere, and Microsoft had one app platform for the whole thing.

HoloLens promised a new era of holographic computing

It was called the Universal Windows Platform, or UWP. With it, you could build one app, using responsive design, that could run on all of these devices.

Moreover, there was the Continuum concept. I mentioned earlier that desktop Windows was designed to adapt to whether you were in laptop mode or tablet mode, but it went beyond that. Phones could be plugged into a monitor and used as a desktop PC, so that same UWP app, placed on a larger display, runs as a desktop app.

Think of it like a website, and how it looks different on your phone compared to your PC, yet it’s the same website.

Microsoft expanded on this too, announcing Windows Mixed Reality in 2016. You could plug a headset into your computer and you’d automatically get a shell for that, again, running the same apps.

Today, pretty much all device types are gone, and without that, the value of UWP is gone. All Windows inbox apps have reverted back to their ‘desktop’ counterparts, and while UWP apps still run, the platform is no longer in active development.

Building bridges for developers

Microsoft was ready to embrace all apps

Even before Windows 8 planning, Microsoft knew it had a very real problem. No one was making new software for Windows. Apps were being supported and new versions were being released, but anything new being created was for the web, and beginning in the late 2000s, mobile. As mentioned earlier, that mobile part and Apple’s App Store is what inspired the Store-centric model of Windows 8. In fact, Windows 8.1 had an early version of ‘universal’ apps that allowed you to create desktop and mobile designs, with a shared code base.

With Windows 10 and UWP, there was a broader strategy. By letting people build apps that targeted all form factors, developers would create new apps, at least in theory. And then, each of the various form factors could leverage apps being built for any other one. If you want to build an app for phones, the desktop can take advantage, and vice versa.

By now, Microsoft knew that it couldn’t just wave a green flag and tell developers to start coding for its platform. Many Windows apps are using code that’s decades old and have become increasingly complex. Asking a company to dedicate resources to remaking that app is a big ask.

Terry Myerson, who was in charge of Windows at the time, introduced the concept of bridges, designed to make bringing your app to Windows easier. There were four of them. Project Centennial let developers finally package their desktop apps and put them in the store; they ran in a container so they couldn’t affect other files on your PC. Project Westminster packages hosted web apps for deployment on the Windows Store.

And then there were Projects Islandwood and Astoria. Islandwood let developers recompile their iOS app code into Windows apps, and Astoria ran Android apps on Windows.

Most of these are long-gone now. Astoria was available in some of the Windows 10 Mobile Technical Previews, but it was killed off before it ever shipped broadly. Islandwood just never got very good. Instead of running iOS apps on your device, which would have been impossible, Microsoft tried to build out a suite of APIs that would just use your Objective-C code. It never kept up, eventually made the project open-source, and it’s more or less faded away.

Project Westminster was fine, but it resulted in a lot of low-quality apps. There were and are plenty of apps on the Microsoft Store that are simply wrapped websites, and thhey’re awful when compared with the native apps those services have for iOS and Android.

Then there’s Centennial, which saw the best adoption of the four. The idea was neat. You could package your desktop app to distribute it, and also take advantage of some UWP features like Live Tiles. However, due to the Intel-specific nature of desktop apps, they were limited to desktop PCs. Today, you don’t need a Desktop App Converter, because as of Windows 11, you can upload any old app to the Microsoft Store.

Live Tiles, Cortana, and Microsoft Edge

Even specific features were dropped over time

I always thought Live Tiles were ridiculous. Even on phones, they had the tendency to just be clutter the way that notifications are today (every app wants to spam you with notifications), and they weren’t updated nearly frequently enough. Apple’s Live Activities are what I wanted Live Tiles to be at the time.

First introduced in Windows 8, I always thought they were a bad idea on the desktop, and in Windows 10 with the more condensed Start Menu, they made even less sense. Today, you won’t find them in Windows at all.

It’s the same story with Cortana. That one debuted in 2014 with Windows Phone 8.1 and made its way to the desktop with Windows 10. Microsoft even made a big cross-platform push with Cortana, releasing mobile apps for iOS and Android. There was a Harman Kardon smart speaker, and the Johnson Controls GLAS thermostat that had Cortana built-in.

It was named after the AI companion in the game Halo, but it wasn’t nearly as helpful. Windows Phone was killed off, voice assistants on desktop typically have low adoption, and third-party voice assistants on platforms that have first-party ones baked in have even lower adoption, so eventually, Cortana was discontinued.

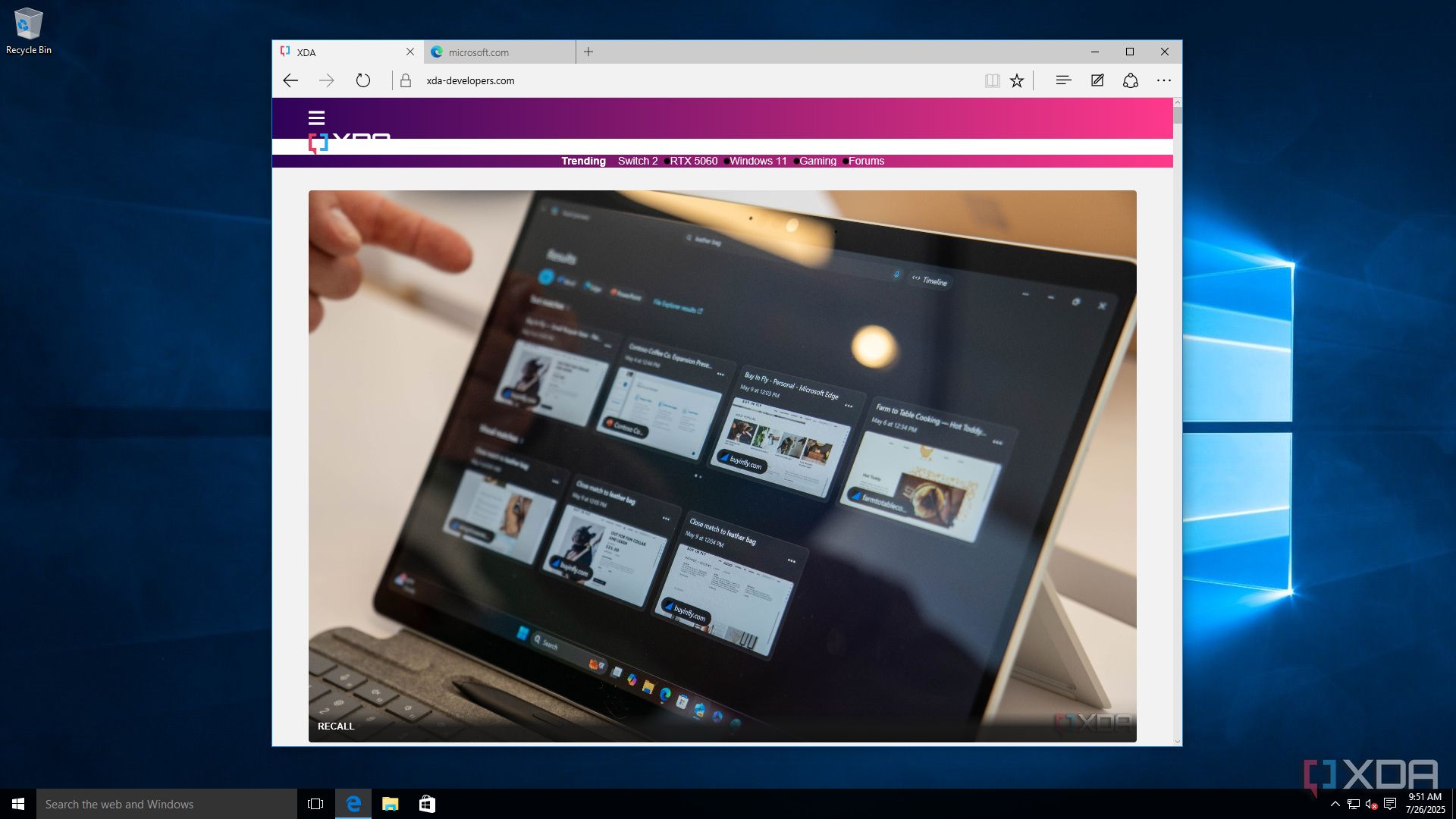

And then there’s Microsoft Edge. I know what you’re thinking. But Rich, I have Edge on my Windows 11 PC right now! Not this Edge.

Six months before Windows 10 launched, Microsoft said it was building a brand-new browser to replace Internet Explorer, codenamed Project Spartan. It promised Cortana built-in, inking for webpages and PDFs, distraction-free reading, and an all-new rendering engine that was going to rely on web standards, something IE hadn’t been the best at.

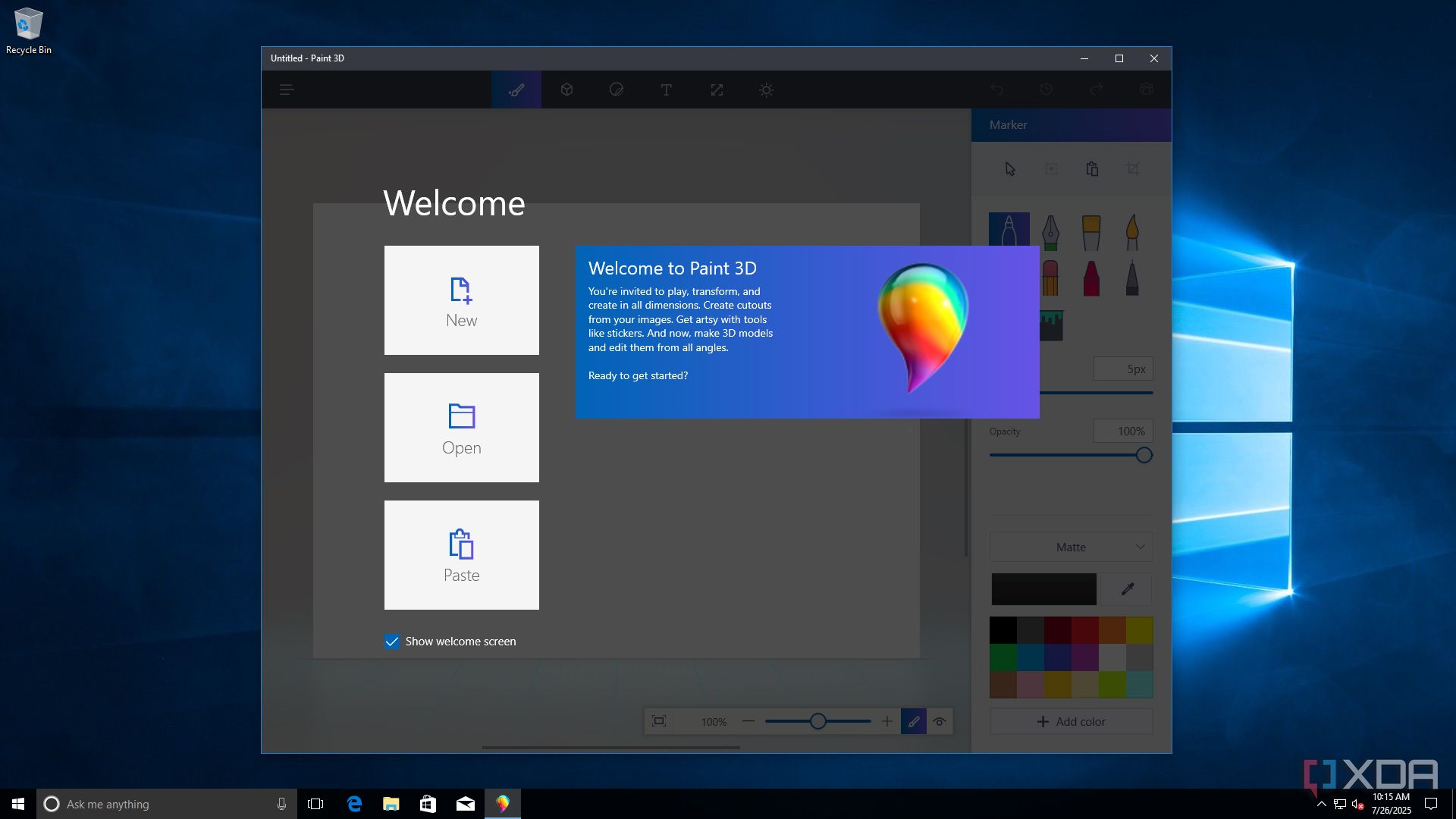

While this came later, Paint 3D was another app that Microsoft launched and later discontinued

It eventually got named Microsoft Edge, and it replaced the crusty old blue ‘e’ logo for Internet Explorer with a fresh new blue ‘e’ logo. The idea behind the logo change was to demonstrate that it wasn’t Internet Explorer, but to also be familiar with people that access the internet by “clicking the blue ‘e’”.

Indeed, Internet Explorer branding had become seriously tainted. Google Chrome had overtaken the lion’s share of browser usage on Windows. And like I just said with Cortana, getting the masses to adopt a third-party product over one that’s built into the OS is extremely hard. People have to hate the first-party product that much.

Unfortunately, Edge didn’t see much success. In December 2018, Microsoft announced that it was going to rebuild Edge from Chromium, effectively making it a de-Googled, Microsoft-ified Chrome. That’s the Edge you see today.

The death of Windows phones

I’ll never forgive them for this

Microsoft was one of the first entrants to the smartphone market, years before the iPhone was introduced in 2007. But of course, with multitouch and later the App Store, Apple disrupted things. With Google entering the market with Android, it had real competition and needed to modernize.

In 2010, Microsoft introduced Windows Phone 7…which was a problem. Windows Phone 7 was based on the same Windows CE that prior Windows Mobile versions were based on, and it was totally unsustainable. When Windows Phone 8 came out in 2012, not a single Windows Phone 7 device got the upgrade, only a Windows Phone 7.8 update that changed up the UI to make it look more like it (similar to Windows RT 8.1 Update 3).

Windows Phone 8 was based on the same NT kernel as Windows, and there was a path forward. In 2014, Windows Phone 8.1 shipped with a bunch of new features, and when Windows 10 was announced later that year, a mobile version was confirmed. The first Windows 10 Technical Preview was available the next day, and a build for phones was going to come later. That should have been the first sign that Windows phones weren’t long for this Earth; Microsoft’s competition was willing to put mobile first.

In January 2015, Terry Myerson promised that Windows 10 would be a free upgrade for anyone running Windows Phone 8.1. In July when Windows 10 shipped, Windows 10 Mobile was still coming later, although you could run the previews. Indeed, at this point, it had been over a year since a flagship Windows phone was made available in the US. I still remember people walking around with the Snapdragon 400-powered Nokia Lumia 830 because that was the best they could get.

In November 2015, Microsoft released the Lumia 550, 950, and 950 XL (it had bought Nokia in 2014), all running Windows 10 Mobile…but it still wasn’t available as an upgrade for existing devices. Finally, Windows 10 Mobile was available as an upgrade on March 17, 2016. Talk about putting a platform on the back burner.

Microsoft also broke its promise of delivering it to all Windows Phone 8.1 devices. A whole bunch of phones were left behind. Moreover, the phones didn’t tell you there was an upgrade. You had to know about it, seek out an app to download, opt in, and then upgrade. It was completely different from how Windows 7 users felt like they were getting spammed and tricked into upgrading to Windows 10.

There were lots of reasons Windows Phone failed. The lack of devices was one of them. The best-selling Windows Phone was the Nokia Lumia 520, a solid 4-inch device that, after a time, you could buy with no contract for $30. It became a race to the bottom. The Lumia 530 had half the storage, a camera with no autofocus, and a worse screen. Then came the Lumia 430 series; yes, there was further to dig to the bottom.

Related

The 7 greatest Windows Phones of all time

The best devices that ran on the best OS

Microsoft saw success in the budget market, and somehow didn’t realize that developers aren’t going to make apps for customers that don’t spend money. Those that did spend money didn’t have a device to buy, with the Lumia 930 being unavailable in the US. Companies like HP entered the market, starting to brand them as 3-in-1 PCs. Of course, they totally weren’t phones anymore, right? Microsoft loses at phones, but not on PCs. So phones became 3-in-1 PCs.

But ultimately, I really think that the failure of Windows Phone was due to a lack of priority from Microsoft. After Windows 10 Mobile version 1703 shipped, people started noticing that version 1709 previews had different version numbers from the PC builds, and they came from a different development branch. I remember a lot of confusion at the time. Were the branches planned to be realigned? There were rumors of an adaptive shell that would run across devices. Maybe this was a gap update while this was being developed?

It never happened. The lame Windows 10 Mobile version 1709 update was the last one, and support ended in December 2019.

And yet, Windows 10 was wildly successful

It’s installed on well over a billion devices

It’s so fascinating to me that despite so many things failing with Windows 10, it was a massive hit. For those on Windows 7, end of life was coming and Microsoft gave them a free upgrade. For those on Windows 8.1, it was a welcome fix for a broken OS.

The Microsoft Store strategy failed, along with the “bridges”. The Universal Windows Platform failed. Live Tiles failed. Cortana failed. The original Edge browser failed. Other Windows 10-specific projects arrived and failed, such as Paint 3D, the UWP Skype app, and OneNote for Windows 10. HoloLens and phone are gone.

And yet, I hear from people every day that say Microsoft can pry Windows 10 from their cold, dead hands.

Part of this is due to some shortcomings in Windows 11, and some of those are by design. Microsoft hadn’t increased system requirements since Windows 7 came out in 2009, and even those were the same as the recommended (not required) system requirements of Windows Vista in 2006.

2020 saw a massive resurgence of the PC industry as more and more people began to work from home, and that sparked Windows 11. This time, Microsoft wasn’t doing it to solve a bunch of problems left behind by previous releases; it was trying to sell new PCs. Windows 11 brought along new requirements for the CPU, TPM, and more. It also only comes in 64-bit for the first time.

Microsoft took a bit longer than its initial projection fo 2-3 years to get to a billion Windows 10 devices, but it got there. Mission accomplished. It solved the issue of competing with itself, and got the masses unified on a modern version of the OS.