Dr Paul E Mullen and his family were living near Dunedin, New Zealand when, one evening in November 1990, they heard gunfire. The shots continued into the night, followed by the distant sound of police and ambulances. At 9pm, a hospital colleague…

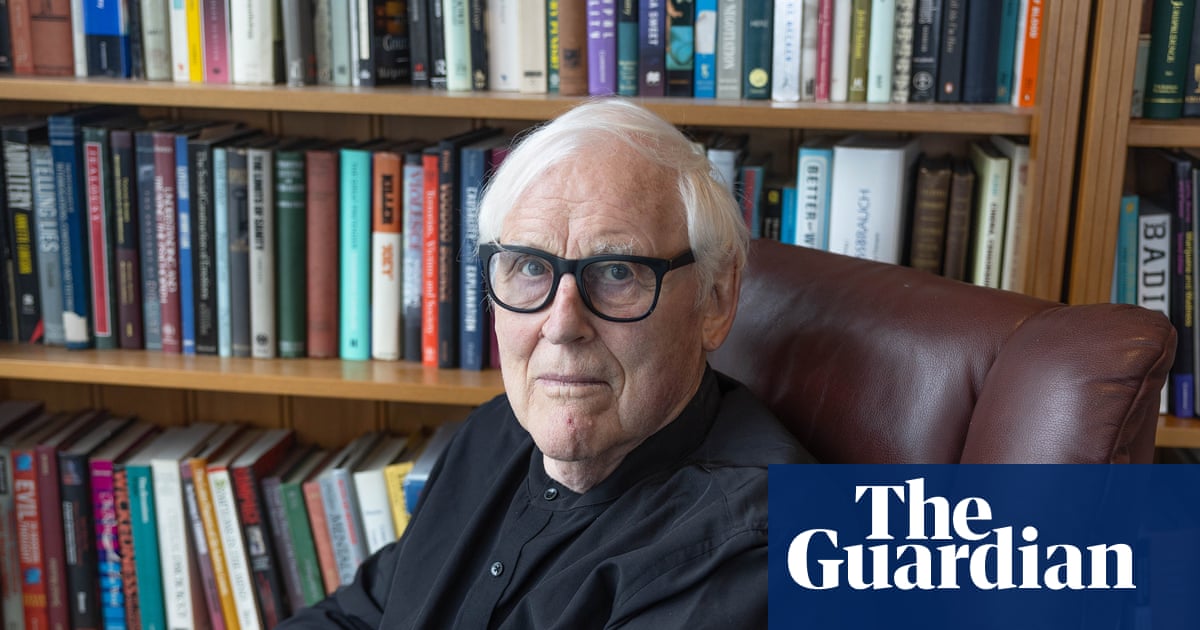

‘They’re not wolves – they’re sheep’: the psychiatrist who spent decades meeting and studying lone-actor mass killers | Australian books