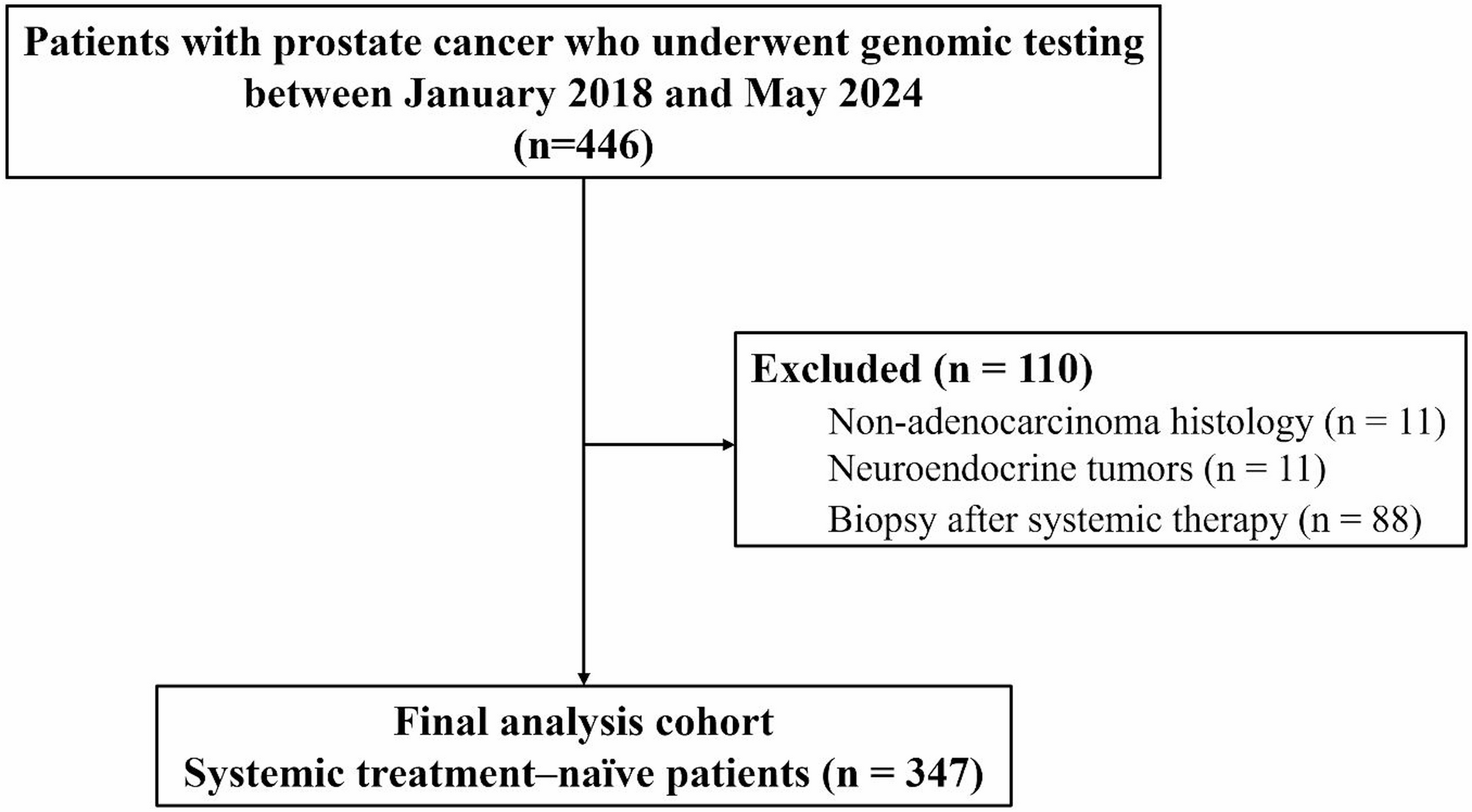

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between IDC-P/ICC and HRR mutations in a real-world cohort of 347 patients with prostate cancer. We further assessed the association between IDC-P/ICC and other molecular alterations, including MMR status, MSI, and TMB. Our study revealed that the presence of IDC-P/ICC was not associated with HRR mutations or MMR status. Notably, mutations in HRR were linked to a younger age and a higher Grade Group, yet they showed no correlation with IDC-P/ICC status or metastatic stage.

IDC-P and ICC are histologically distinct entities but exhibit similarly aggressive clinical courses, both being associated with advanced disease stages, recurrence, and poor outcomes [24, 25]. Although the 2019 ISUP consensus recommends that IDC-P and ICC be reported separately due to their distinct diagnostic and prognostic implications, in real-world practice, this distinction can be challenging because of overlapping morphologic features [21, 26]. Accordingly, the NCCN guidelines recommend germline testing for patients with either IDC-P or cribriform morphology, reflecting their shared clinical significance and association with genetic mutations [11]. At our institution, consistent with contemporaneous diagnostic practice during the study period, IDC-P and ICC were evaluated morphologically without the use of routine basal cell immunohistochemistry and were reported together rather than separately. While this approach reflects actual clinical practice, it differs from current consensus recommendations and may have introduced variability in histologic classification, which should be considered a limitation of our study.

Additionally, our data revealed discrepancies between biopsy and prostatectomy findings. While most IDC-P/ICC cases were detected on biopsy, approximately 13% were identified only on prostatectomy specimens, and one case was positive on biopsy but negative on prostatectomy, suggesting sampling variation or intratumoral heterogeneity. These findings align with prior studies showing the limited sensitivity of biopsy. Ericson et al. [27] reported a sensitivity of 56.5% with no added benefit from MRI fusion, and Masoomian et al. [28] found that biopsy detected IDC-P/ICC in only 26.9% of cases compared with 51.8% at prostatectomy, corresponding to a sensitivity of 47.2%. More recently, Bernardino et al. demonstrated that false-negative biopsies were associated with higher pathological stage and increased risk of biochemical recurrence [29]. Taken together, these results highlight that prostate biopsy has limited sensitivity for IDC-P/ICC detection, as reflected by the 13% underdetection rate in our cohort. This reinforces that biopsy IDC-P/ICC status alone is insufficient to guide genetic testing and underscores the need to integrate additional clinical and pathological factors.

Contrary to previous studies suggesting a link between IDC-P/ICC and HRR mutations [7,8,9], our multivariable analysis revealed that IDC-P/ICC is not a significant predictor of HRR mutation status. These findings are in line with those of recent studies [30, 31]. Mahlow et al. [31] concluded that pathologic patterns alone are insufficient to predict HRR mutations in advanced prostate cancer. While their study included only six IDC-P cases, our larger cohort of 254 patients with IDC-P/ICC provides robust support for their conclusions. Lozano et al. [30] found no significant differences in IDC-P/ICC between germline BRCA2 (gBRCA2) carriers and non-carriers. However, they discovered that bi-allelic BRCA2 loss in primary prostate tumors was independently associated with both IDC-P and cribriform morphologies. They proposed that tumors with a gBRCA2 mutation and intact second allele may preserve some BRCA2 function, potentially preventing these histologies. Our study extends these findings by examining a broader spectrum of HRR genes, showing that somatic HRR mutation status is not indicated by the presence of IDC-P/ICC. Since our cohort primarily consisted of metastatic cases, it is important to note that while some non-metastatic patients were included, further studies are required to fully understand the role of IDC-P/ICC in localized prostate cancer. With HRR gene mutation prevalence around 25% in metastatic disease [32] but less than 10% in localized disease [33], the consistent lack of association between IDC-P/ICC and HRR mutations across studies raises questions about the appropriateness of relying on cribriform pattern status as a trigger for genetic testing, particularly as outlined in current NCCN guidelines [11].

Another potential explanation for the discrepancy between IDC-P/ICC and HRR mutations lies in our limited understanding of IDC-P pathogenesis and its underlying molecular events. The pathogenesis of IDC-P can vary, with most cases resulting from retrograde spreading of adjacent aggressive prostate cancer into ducts, but de novo IDC-P can also occur [2]. These different origins might contribute to the observed variability in HRR gene alterations in IDC-P/ICC. The heterogeneity in IDC-P origins could explain why our study and others have found inconsistent associations between IDC-P/ICC and not only HRR but also other mutations. Contrary to previous studies’ results [9, 10], our data do not show a statistical difference in MMR mutations between IDC-P/ICC positive and negative groups (2.8% vs. 1.1%, P = 0.687). Additionally, another potential poor prognostic marker, MSI-high status, was also not significantly different between the two groups (1.1% vs. 1.2%, P > 0.999). These findings prompt us to reconsider the use of IDC-P/ICC as a sole indicator for genetic testing and suggest that a combination of clinical and pathological factors may provide better stratification for identifying patients who would benefit from comprehensive genomic profiling. Given the relatively low prevalence of IDC-P/ICC, future research would benefit from multicenter collaborations with centralized pathologic review of specimens for genetic testing. Such large-scale efforts could provide more definitive insights into the relationship between IDC-P/ICC and molecular alterations.

HRR mutations occur not only in metastatic disease but also in locally advanced or regional diseases. Our study found that HRR gene mutations are associated with high Grade Groups and younger age at diagnosis, regardless of metastatic status. While current guidelines focus on metastatic disease for recommending genetic testing, emerging evidence suggests HRR status may provide valuable prognostic information even in localized disease [22]. With PARP inhibitors now showing efficacy in metastatic prostate cancer [13,14,15,16], there is potential for their application in localized disease as well [34]. This evolving landscape underscores the need for a more stratified approach to genetic testing in prostate cancer. Based on our study, a combination of younger age and higher Grade Group may be good indicators for genetic testing, rather than relying solely on a single morphological factor.

The major limitations of this study are its retrospective, single-center design, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader populations. Additionally, the lack of a standardized NGS testing protocol introduces potential selection bias, as genomic testing was performed at the discretion of the treating physician and was most often applied to patients with aggressive clinicopathological features, rather than uniformly across all prostate cancer cases. Furthermore, as we collected somatic NGS test data, the results cannot be directly applied to germline findings. Another limitation is that IDC-P and ICC were assessed morphologically without routine basal cell immunohistochemistry and were not reported separately, which may have introduced variability in classification. Despite these limitations, our study provides real-world evidence of the correlation of IDC-P/ICC with HRR, MMR, MSI, and TMB, which are important predictors in the era of molecularly targeted systemic treatments.