Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

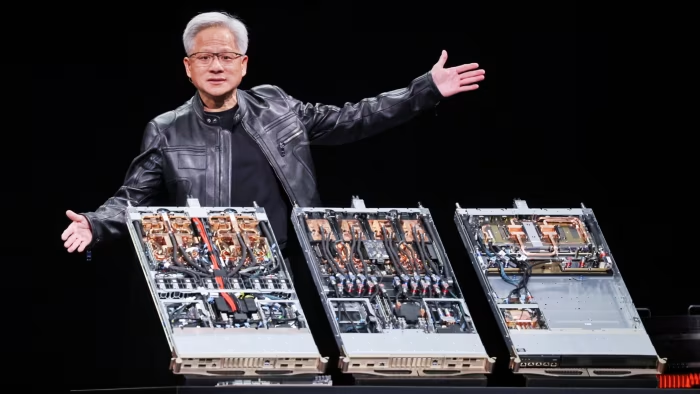

China is going to win the artificial intelligence race, says Jensen Huang. At first glance, it is easy to assume Nvidia’s billionaire founder is just talking his book. Nvidia does stand to gain the most from any narrative that encourages the US to step up its investment in AI or ease regulatory restrictions on its development, thus boosting demand for Nvidia chips. But does he have a point?

Not long ago, about a fifth of Nvidia’s data centre revenue came from China. Its fortunes depend on a steady stream of orders for its chips from governments, cloud providers and AI research labs around the world. The fear of China pulling ahead in AI reinforces that demand.

Still, Huang’s warning may hold some truth. AI development has started shifting from being limited primarily by high-end chip availability to being constrained by electricity supply.

A GPT-4 model can use up to 463,269 megawatt-hours of electricity per year, according to research by academics at the University of Rhode Island, University of Tunis and Providence College. That is more than the annual energy consumption of more than 35,000 US homes. This demand reflects the expanding share of AI workloads in data centre electricity consumption. Global use of electricity by data centres is projected to more than double by 2030, and will reach about 1,800 terawatt-hours by 2040, enough to power 150mn US homes for a year, according to Rystad Energy.

As a result, the price and availability of power will increasingly determine the pace of AI progress. Here, China has a head start. Last year, it added a record amount of renewable energy capacity, mostly from new solar and wind installations. Solar power alone expanded by about 277 gigawatts, while wind contributed about 80GW, bringing total new renewable capacity to more than 356GW, far exceeding total capacity in the US.

This renewable surge is part of a bigger plan. Beijing has linked industrial policy to its efforts to reinforce the national grid, developing large solar projects in Inner Mongolia, expanding hydropower in Sichuan and building high-voltage transmission lines to move cheaper inland electricity to coastal demand centres.

Local authorities are also granting preferential electricity rates to companies such as Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance to boost local AI computing. These subsidies help to offset the lower efficiency of domestic chips from Huawei, allowing China to train AI models at a lower overall cost.

Meanwhile, in the US, wholesale electricity costs have been rising, with prices today as much as 267 per cent higher than five years ago in areas near data centres. But investment in many types of renewable projects, including large-scale wind and solar, fell in the US during the first half of the year, reflecting policy shifts and regulatory uncertainty. The White House has also detailed an executive order ending subsidies for wind and solar power.

Some argue that China’s energy advantage cannot fully compensate for its lag in chips and models. Indeed, Nvidia’s H100 and Blackwell graphics processing units remain ahead of Chinese alternatives such as Huawei’s Ascend 910B in terms of memory bandwidth and performance.

That imbalance would have been critical in the hardware-dominated phase of technological competition, when access to advanced chips powering computers and smartphones determined who led entire industries. The US, for example, curbed Huawei’s ascent by restricting its supply of high-end chips starting in 2019.

Yet the difference today is that energy has now started to scale faster than transistors: chip performance gains have slowed to single digits while China’s renewable generation continues to expand at double-digit rates each year. Declining electricity costs expand the amount of computation that can be purchased for the same budget, and expanding grid capacity allows models to be trained more frequently for longer durations.

The race to master AI is new but it is part of a centuries-old story. Throughout history, every technological superpower has risen on the back of cheap energy. Cheap, abundant coal powered Britain’s Industrial Revolution. In the US, oil and hydroelectric power fuelled its dominance in manufacturing and military technology during the 20th century.

The battle to control AI is often framed as a contest for chips and the controls that govern them. But power will belong to those who can keep the AI models running.

june.yoon@ft.com