This post was originally published on NCSOFT.com and is republished here with permission.

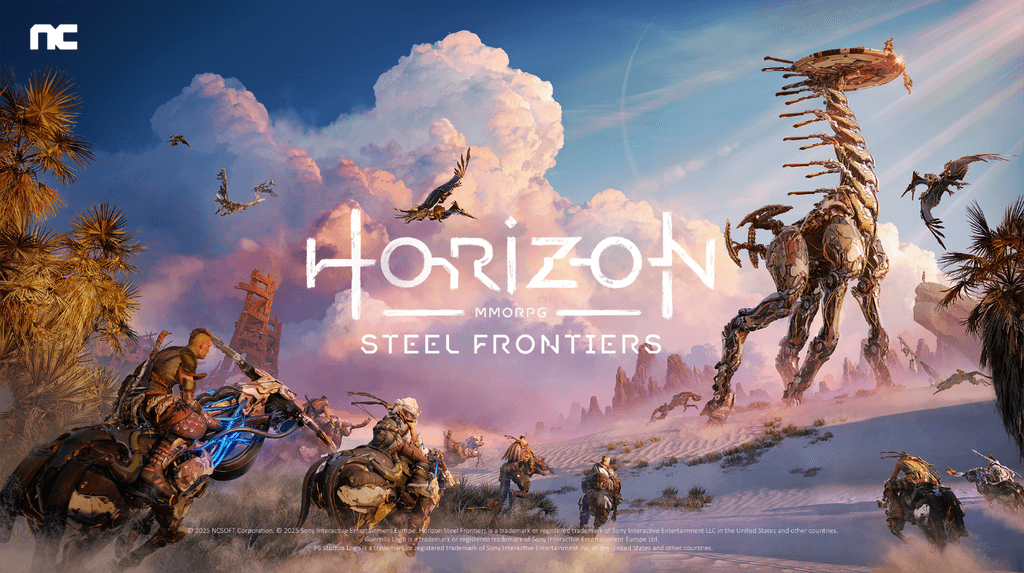

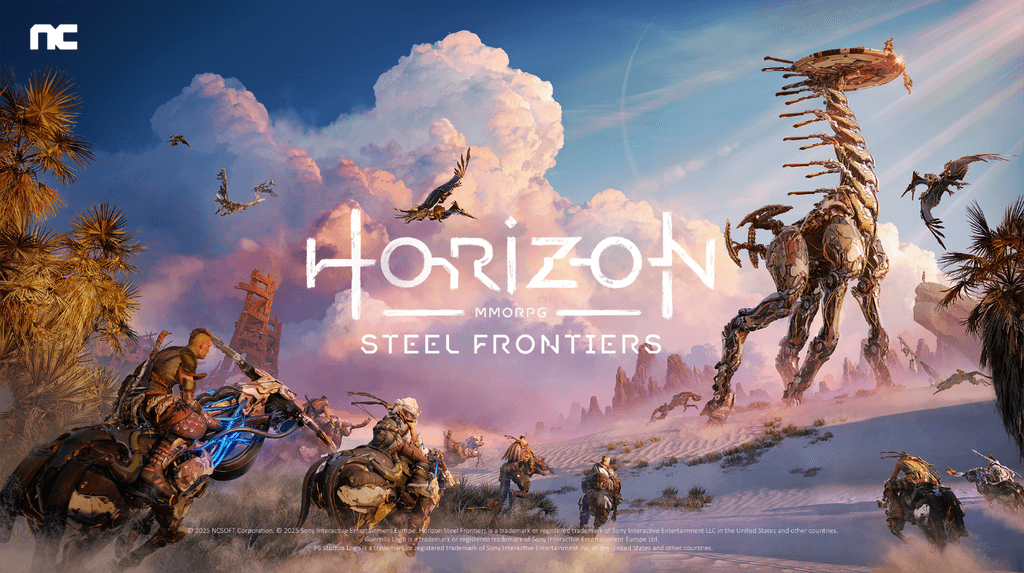

NCSOFT Kicks Off G-Star 2025 with Surprise Announcement and Trailer Showcasing Horizon’s Signature Hunting Action and Advanced Combat…

This post was originally published on NCSOFT.com and is republished here with permission.

NCSOFT Kicks Off G-Star 2025 with Surprise Announcement and Trailer Showcasing Horizon’s Signature Hunting Action and Advanced Combat…