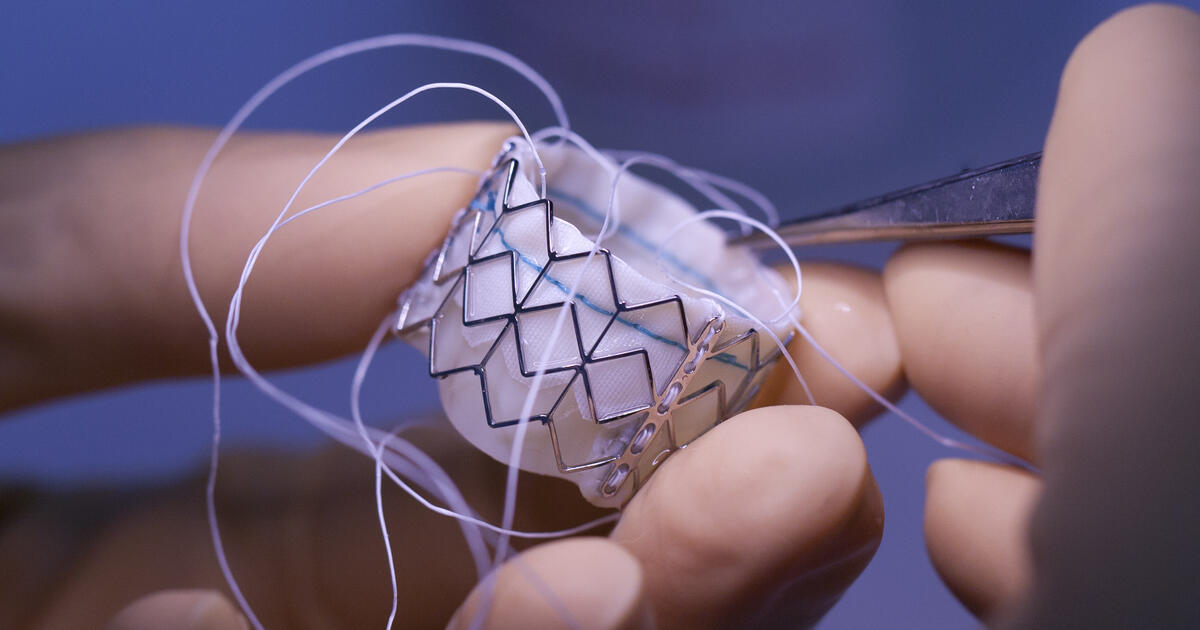

The Paris Central Division of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) ruled (40-page / 1.68MB PDF) that companies in the Meril Life Sciences group (Meril) infringed a European patent relating to a prosthetic heart valve and a delivery assembly. The patent, a third-generation divisional patent, belongs to US-based Edwards Lifesciences Corporation (Edwards). The patent was found to be valid as amended by an auxiliary request and the court granted an injunction prohibiting Meril from supplying a rival valve product in the UPC contracting member states in which the patent is in force. However, the injunction does not apply to all versions of Meril’s valve.

As Meril is the only manufacturer of an extra large version of the type of valve at issue, the Paris court considered there would be a public interest in exempting those versions of the product from the scope of the injunction. This is because it acknowledged that some patients who suffer from aortic stenosis – where the aortic valve into the heart is narrowed – and who would need an extra large valve to be implanted to address the condition could be left without an adequate treatment if those products were included within the scope of the injunction. The court reiterated that to rely on such a public interest defence, “it is essential to demonstrate that [it] is the sole available treatment method or that it represents an improvement upon a known treatment method, resulting in a notable enhancement in patient care”. The exemption in the present case only extends until such time as another equivalent treatment becomes available.

Sarah Taylor of Pinsent Masons, an expert in life sciences patent litigation, said the case provides lessons for businesses on both sides of a patent dispute.

“Injunctions remain an important remedy in a finding of infringement, but they may, in some circumstances, be limited for reasons of public interest,” Taylor said. “Businesses defending against an injunction should take the opportunity to narrow the reach of injunctions where there may be a real public interest reason for doing so. Those seeking injunctions should be aware that such relief may be limited where no alternative treatment method is available.”

The proceedings before the Paris court were initiated by Meril, as part of a long-running dispute between the parties. It asked the court to revoke Edwards’ patent, claiming that it was invalid for added matter, lack of novelty and lack of inventive step. Edwards filed an application to amend the patent and a counterclaim for infringement. After the parties had filed their written pleadings, Edwards requested, and was granted, leave to amend its counterclaim to explicitly extend it to cover Meril’s new heart valve product and delivery system. The court ultimately rejected Meril’s revocation action, maintained the patent as amended by an auxiliary request and upheld Edwards’ counterclaim for infringement.

In assessing the patent’s validity, the Paris court endorsed case law that the Munich Central Division developed last year on the question of inventive step.

Patents can only be obtained for inventions if those inventions are, among other things, new, not obvious, and have an industrial application. To pass the obviousness test, applicants must be able to show that their new product or process delivers an inventive step – i.e. there is a substantive technical advance that someone skilled in the relevant area would not be able to work out easily using their own know-how and information available to them.

Last year, in a case between Amgen on the one hand and Sanofi and Regeneron on the other, the Munich Central Division said that the question of whether there has been an inventive step taken should be assessed holistically.

The first step, it said, is to determine a “realistic starting point” in the prior art that would have been of interest to the skilled person considering a similar “underlying problem” as that which the patent claimed to solve. It said this ‘realistic starting point’ may be one of several and does not need to be the most promising starting point.

The next stage, the Munich court determined, is to ask whether it would be obvious for the skilled person to arrive at the claimed solution in the patent from the ”realistic starting point”. If the skilled person would be motivated to consider and implement the claimed solution in the patent as a next step, then the patent is obvious.

Taylor said the Paris court took the same approach in the Meril v Edwards case, confirming the need for a ”holistic” assessment, and highlighted guidance the court provided on what could constitute a ”realistic starting point” when assessing inventive step.

The court said: “A realistic starting point is a document ‘of interest’ for solving the objective problem. In this regard, it may be assumed that realistic starting points, in general, are the pieces of evidence which disclose the main relevant features as those of the challenged patent and for that reason have constituted the basis for the developing of the inventive idea and/or which address the same or a similar underlying problem.”

Taylor said, however, that the ”holistic approach” backed by the UPC in this case differs from the “problem-solution approach” used by the European Patent Office (EPO) to assess the question of inventive step, which requires the identification of the closest piece of prior art. It had been expected that the UPC would adopt this strict problem-solution approach, and while some divisions of the court have, others, including the Paris Central Division in this case, have deployed the holistic approach. UPC Court of Appeal clarification will ultimately be required to determine binding UPC case law on the issue, but Taylor noted that this difference could have “some implications for identifying the relevant starting point for solving the underlying problem and potentially any experts the parties may want to instruct”.

Taylor said, though, that the different approaches did not lead to a different outcome in the context of the dispute between Meril and Edwards, noting that Meril had lodged parallel opposition proceedings before the EPO before which its arguments pertaining to inventive step were also unsuccessful.

In the context of the parallel EPO proceedings, Taylor said it was noteworthy that the Paris court had exercised its discretion not to ‘stay’ its proceedings – that being, wait for the EPO proceedings to conclude before deciding the dispute before it.

“Clients with proceedings at the EPO and UPC should bear in mind the UPC’s discretion to stay/not stay proceedings,” Taylor said. “The bar to granting a stay is high, with the court keen to meet its aim of reaching a final decision within 12 to 14 months of proceedings being issued and willing to decide matters independently.”

In the present case, in exercising its discretion against a stay in this case, the Paris court considered the fact that neither party had requested a stay, which the court took as implicitly demonstrating the parties’ interest in a prompt decision by the court. Furthermore, at the time the Paris court was informed of the pending opposition proceedings before the EPO, the UPC proceedings were already at an advanced stage – the written phase had concluded, the interim conference had been held, and the oral hearing was imminent. The Paris court also observed that any stay of the proceedings would have the effect of postponing a decision in the infringement action, thereby frustrating Edwards’ interest in a swift protection of its exclusive right.

Taylor highlighted that it took Edwards less than a year from the point it extended its infringement counterclaim to obtaining an injunction against Meril from the Paris court, an injunction which also covers Meril’s new valve product. She said the speed at which the UPC can operate to grant patent rights holders such relief, and the front-loaded nature of UPC proceedings, is something businesses need to factor into their litigation and commercial strategy and planning.

“Parties should collate relevant information as early as possible to ensure written pleadings can be prepared and submitted in the short time frame,” Taylor said. “Additional evidence and information should be considered, collected and prepared early if a public interest defence may be brought into play. Thought should also be given to the approach the UPC may take to assessing inventive step, especially if there are also parallel opposition proceedings at the EPO – the identification of a ‘realistic starting point’ for solving the objective problem is important for the UPC, although it is debateable whether the two ‘different’ approaches are all that inconsistent.”

The European patent at issue in this case is part of a wider family of patents in the longstanding dispute between Edwards and Meril in relation to heart valves. Edwards was successful in pursuing infringement claims against Meril in relation to another of its patents relating to some of Meril’s heart valve products before the Munich Local Division of the UPC last year.