Study design

We adhered to the GUIDED guideline for reporting for intervention development studies when describing the development process in detail [10].

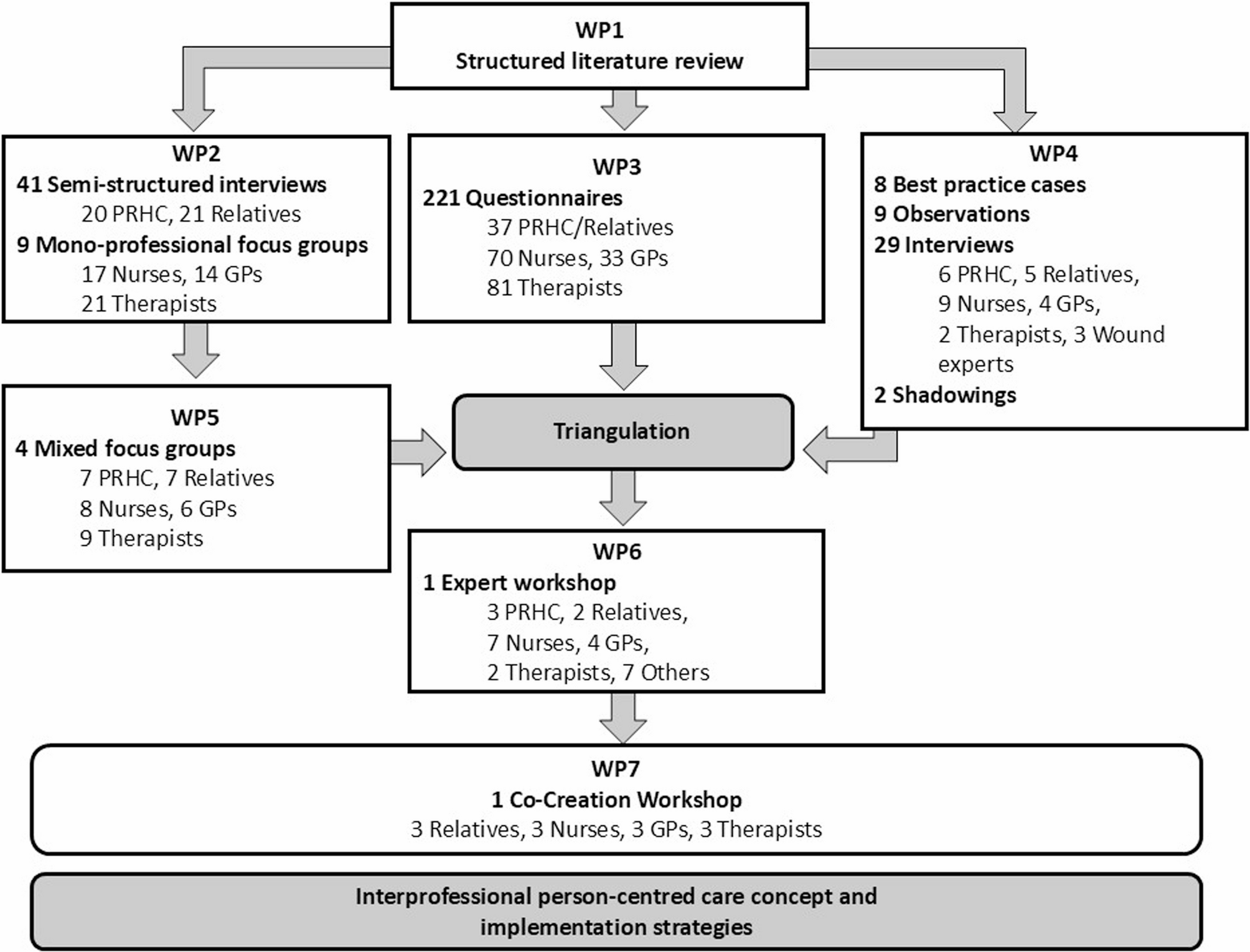

The interprofessional person-centred care concept interprof HOME was developed according to the MRC framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions [11] using a multistep mixed methods approach. This paper describes the development phase, where we consider the core elements of the MRC framework: considering context, developing and refining program theory, engaging interest holders, identifying key uncertainties, refining the intervention, and economic considerations [11]. The development process consisted of six work packages (WP1-6) that were carried out simultaneously or consecutively (Fig. 1), as described in detail in our study protocol [12]. In addition, we conducted a co-creation workshop (WP7). The study took place between May 2021 and September 2023, and the co-creation workshop occurred in October 2024.

Study design for the interprof HOME development, WP = work package

Study setting

The study was conducted in the city and surroundings of Göttingen, Hamburg, Lübeck and Cologne. The researchers of the respective research teams had various areas of professional expertise and experience in general practice, nursing practice, nursing pedagogy and nursing research, public health, organizational and corporate development, medical law, physiotherapy, or occupational therapy. In addition, the study team was supported by a multiprofessional advisory board made up of patient representatives, members of self-help groups and professional carers.

Participants and sampling

Recruitment of participants for interviews (WP2), focus groups (WP2 and WP5), best-practice cases, observations, shadowings (all WP4) and co-creation workshop followed the same procedure: professionals were identified using local registers and invited to participate in the study by letter and later by telephone. The PRHC and relatives were recruited through outpatient nursing services, self-help groups, GPs and therapists. Additionally, professionals identified from local registers were invited to participate in the survey via email, followed by two reminders (WP3). The PRHC and relatives were recruited using notices in care support centres, information in newsletters or websites of caregiving relatives or self-help groups and presentations of the study in meetings of self-help groups. The experts for the workshop (WP6) were invited on the basis of their experiences, the recommendations of the advisory board or professional contact. The researchers contacted them via email or telephone. The eligibility criteria for participants are described in our study protocol [12]. For the co-creation workshop (WP7) patients, relatives, registered nurses, GPs and therapists were invited to discuss the components of the interprof HOME concept after WP6. They were purposefully recruited with regard to heterogeneous characteristics (gender, age, and residence).

Data collection and analysis

Step 1: identifying existing evidence and theory

Initially, existing evidence was synthesized by carrying out two literature reviews.

Literature review (WP1)

First, a literature review of professional providers’, PRHC’, and relatives’ perspectives on collaboration and communication over the previous 10 years was conducted. The research questions were: (1) What is the perspective of general practitioners/professional caregivers from outpatient care services/therapists on cooperation/communication with other caregivers? (2) What is the perspective of PRHC/relatives on cooperation/communication with professional caregivers? We conducted systematic searches in the Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO for studies published in English or German. The search was performed by different members of the research team, with five separate foci: general practitioners, nursing staff, therapists, relatives, and PRHC. For all searches, we applied a core set of MeSH terms (“Interpersonal Relations”, “General Practitioners”, “Home Care Services”, “Nurses”, “Occupational Therapists”, “Physical Therapists”, “Patients”, “Family”). Search term combinations were adapted according to the respective perspective.

In a second literature review, intervention studies on strategies for promoting interprofessional collaboration in PRHC outpatient care were reviewed. Systematic searches using sensitive search strategies were carried out in the databases MEDLINE (via PubMed), Cochrane Library, CINAHL and PEDro, coupled with manual searches in citations lists of relevant articles. A primary search strategy was initially developed for the MEDLINE database combining major subject headings and freetext vocabulary on the concepts ‘outpatient care’ and ‘interprofessional collaboration’; this strategy was subsequently adapted to the other databases.

Step 2: exploring the perspective of all involved groups

To develop a customised and successful care concept, we used the participatory approach by considering the perspectives of all the groups involved and working with them to enable the inclusion of their different needs and perspectives.

Qualitative interviews and mono-professional focus groups (WP2)

The interprofessional healthcare situation of the PRHC was explored via semistructured interviews (facilitators: BT, RD, CH, AM, US, TH, and LS) with the PRHC and relatives. After obtaining informed consent, trained members of the research team conducted open guideline interviews in face-to-face, online or telephone interviews The results from WP 1 served as the basis for developing the interview guides for WP2. For guidelines for interviews with PRHC and relatives see Supplementary Material 1 in [19]. Monoprofessional focus groups, either with GPs, nurses from outpatient nursing services or therapists, were conducted in the four study centres using video conferences (facilitators: BT, RD, CH, AM, US, TH, AK). For interview guideline for monoprofessional focus groups with nurses, GPs and therapists see Supplementary Material 2 in [19]. The barriers to and facilitators of interprofessional person-centred care were discussed, and first, ideas for improvement were collected.

The interviews and focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed and checked against the audio recording, and the identifiers of persons and locations were replaced with pseudonyms. The interviews and focus groups were analysed per person group using qualitative content analyses in teams of at least two researchers from different centres [20].

Survey (WP3)

In a multicentre survey, PRHC/relatives, GPs, nurses and therapists completed questionnaires on the following four topics: (1) previous cooperation in home care, (2) possibilities of cooperation, (3) starting points for cooperation, and (4) ideas for measures to promote interprofessional cooperation. In order to take into account the perspectives of all those involved in the care of PRHC, we created four different questionnaires. Data were collected anonymously via the “SoSci Survey” online platform [21] and analysed descriptively using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, version 28.0.

Best-practice cases (WP4)

Data on eight home-care constellations considered “best-practice cases”, that is, cases in which all involved actors agreed that collaboration was working particularly well, were collected through non-participatory observation of professionals’ home visits and semi-structured interviews with the PRHC, relatives or close contacts, nurses, GPs, therapists and wound experts (facilitator: MD). To select best-practice cases, we asked professionals (GPs, nurses, therapists) to identify a patient case they perceived as exemplary in terms of collaboration. They then asked the other actors involved (patients, relatives, other professionals) for their consent to participate. If all parties agreed and confirmed the high quality of collaboration, the case was included as a best-practice example. The guiding themes in interview were (1) general overview of the care and collaboration taking place in this specific case, (2) coordination and information exchange between actors involved, (3) home visits of professional actors, (4) space (role/use of living space for care and collaboration), (5) problems, (6) changes in conditions/hospitalization and (7) general idea of (interprofessional and professional/non-professional) collaboration. For the professional actors we also included: (8) differences of this case compared to other cases. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and pseudomized to enable a detailed analysis of the guiding themes. During the observations, notes were taken. During preparation and follow-up of observations, informal conversations were held with the different professional and non-professional actors. In addition, two nurses from outpatient nursing services were shadowed during the workday (18 hours in total) to gain insights into the organization of their daily routines, and notes were taken. A case-based analysis based on principles of grounded theory was conducted for the evaluation proceeding from individual case analyses to a systematic cross-case comparison [22, 23]. We focused on the practices and measures of the individual actors that fostered collaboration and then compared these across the eight cases.

Mixed focus groups (WP5)

Mixed focus groups (facilitators: BT, RD, CH, AM, US, and TH) with samples of representatives from all parties were involved to outline the components of the interprofessional person-centred care concept. The findings of WP1 to WP4 were used as a basis for developing the guideline for the mixed focus groups with the following topics: A: presentation and discussion of barriers and facilitators to collaboration: (1) availability of relatives and professionals, (2) care partnership between relatives and professionals, (3) lack of established processes: fixed contact person, shared (digital) documentation, and communication system and (4) being known and trust; B: presentation and discussion of wishes/ideas for improved collaboration: (1) reducing the burden on patients and relatives regarding care organization and coordination, (2) contact information and appointment coordination, (3) (digital) documentation and communication tools, (4) personal (direct) exchange, (5) interprofessional education and training, (6) fixed contact persons and/or care teams. C: discussion of future interprofessional collaboration in PRHC care: (1) feasibility, (2) implementation strategies, (3) involved actors. The first two topics focus on the content reported in the WPs. The third topic focuses on the needs and preferences of PRHC and relatives in order to ensure person-centred, high-quality healthcare at home. Focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed and checked against the audio record, and the identifiers of persons and locations were replaced with pseudonyms. Analyses were performed using content analyses with a focus of topics and subtopics in the analysis process [20].

In a second step we used joint displays [24] with regard to the identified categories focusing on the areas of action in which interprofessional cooperation needs to be improved, we were able to compare the results of WP5 simultaneously and in relation to the results of the interviews and focus groups (WP2), of the survey (WP3) and best-practice cases (WP4) in a tabular presentation and write a summary of the content. The findings, containing a preliminary list of potential components of the care concept (areas of action), were sent to the experts of the workshop (WP6) in advance.

Step 3: modelling the first version of the concept and implementation strategies

Expert workshop (WP6)

During an online expert workshop, the participants discussed, adapted and combined the components of the care concept that had been drafted. The experts were allocated to four break-out groups focusing on different topics which the preliminary areas of action were assigned to: (1) expansion of the scope of action for the nursing staff and therapists and continuing education to increase competencies in nursing and in medical and therapeutic activities for the professional groups involved in home care as well as for relatives; (2) coordination and planning of joint home visits; (3) communication by telephone, face-to-face communication, documentation and coordination of appointments; and (4) digital communication/documentation systems. Each group assembled a mix of professional and PRHC/relatives perspectives. Within these group sessions, the participants reflected on the relevance and feasibility of these areas and discussed, based on their experiences and presented results, specific measures that should be implemented. For each measure they discussed the aims, involved parties and their roles, occasions and indications for implementation, potential impact on trust-building between PRHC, relatives and professionals, specific wishes and needs of PRHC and implementation considerations. One facilitator and one person taking minutes were present in each digital (breakout) room. The results of the break-out groups were discussed in a subsequent plenary session, leading to a preliminary list of intervention components and associated measures. In a subsequent online survey during the meeting, the participants assessed the relevance and feasibility of these measures. After the results of this survey were discussed, the measures were prioritized by selection of those that were most frequently chosen by the participants in a second live online poll. In this poll, that closed the workshop discussion on the intervention components, each participant could choose up to three measures (one in the area of care coordination, two in the other areas). Thereafter relevant factors for implementation were discussed in four groups via SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis. Additionally, relevant context factors across measures were identified. Finally, implementation strategies were derived and briefly discussed using the CFIR-ERIC strategy matching tool [25, 26]. The expert workshop was conducted over two half-days and was logged and documented.

Step 4: first version of the interprofessional person-centred care concept

The research team refined the components of the care concept through several meetings, considering the findings across all WPs with the main emphasis on the expert workshop. The components of the new interprofessional care concept and the implementation strategy were documented in an intervention protocol according to TIDieR [27] (Additional file 1).

Step 5: modelling the final version of the concept and implementation strategies

Co-creation workshop (WP7)

As the first version of the interprof HOME concept was refined by the research team from the collection of topics from the expert workshop, its suitability for daily use in routine care needed to be proven. We conducted a co-creation workshop in order to explore the relevance, feasibility and robustness of the components. Therefore, a two-day co-creation workshop was held in person at the Department of General Practice in Göttingen, each lasting 4 hours [28, 29]. Here, implementation of the components was simulated against real-life care scenarios. In advance, the first version of the care concept interprof HOME was sent to the participants via email. On the first day, the participants were divided into two subgroups. Each subgroup consisted of individuals from different groups (relatives, registered nurses, GPs, and therapists) to ensure constructive multi-perspective exchange. During the sessions, both subgroups adapted half of the components according to different care scenarios in a simulation game. The findings were documented by mapping methods on both days. On the second day, the interim adapted interprof HOME concept was briefly presented to the (partially new) participants. Now, the two subgroups adapted half of the components again, according to the other care scenario, in a simulation game. In a common session, the subgroup results were analysed, and the new components were consented. These components were sent to the participants for additional comments. Afterwards, the concept was finalized by the research team.