A new NASA-backed study has found an unexpected effect of Greenland’s melting ice: the runoff is causing a surge in tiny ocean life. This could have implications for the marine ecosystem and the global carbon cycle.

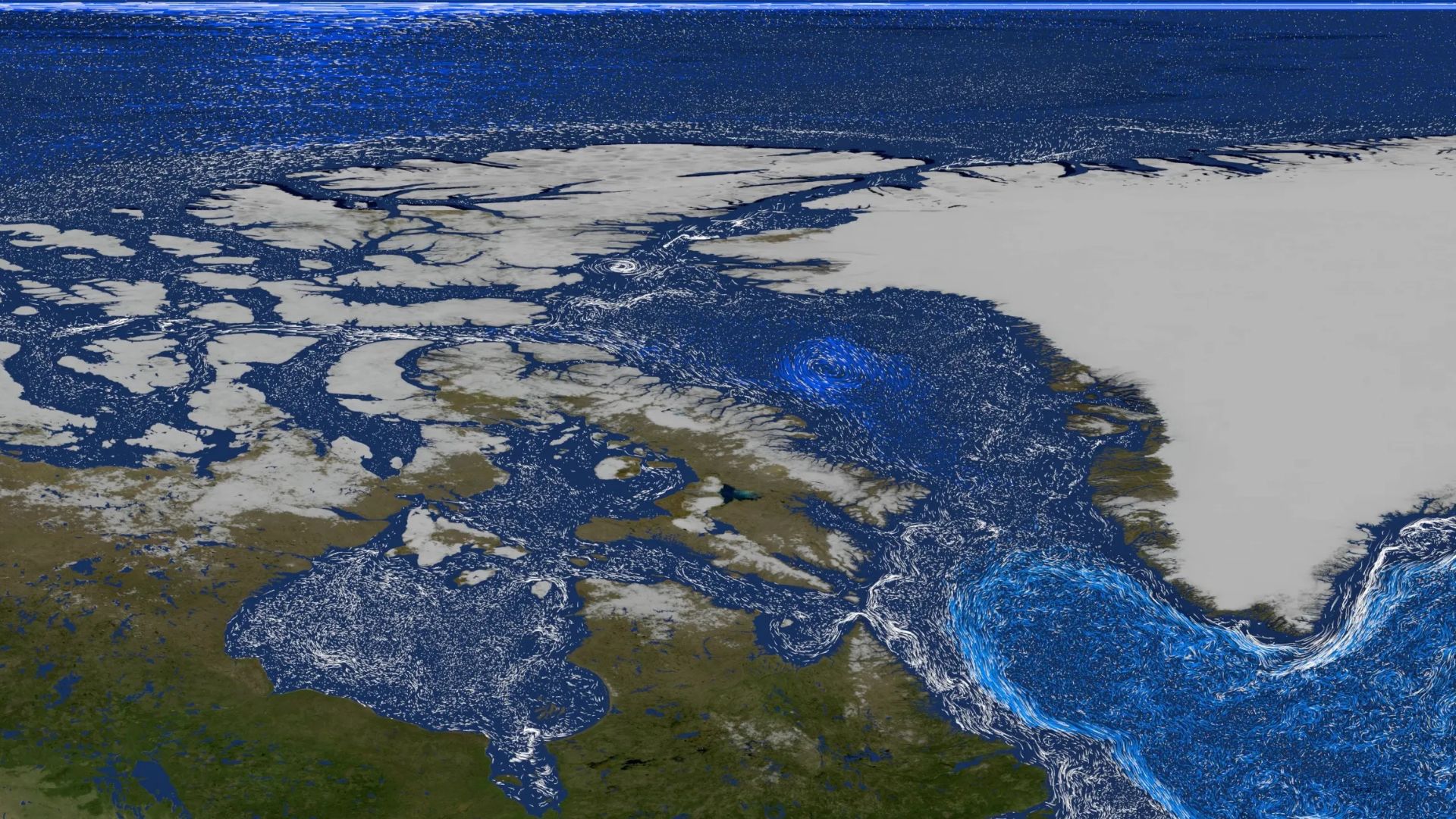

Scientists have used powerful computer models to study the difficult-to-reach ocean waters around Greenland.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge developed the ECCO-Darwin computer model.

This model combines billions of data points to simulate the relationships between ocean physics and marine life, allowing researchers to study how melting glaciers affect the ecosystem.

How is ice melt boosting phytoplankton in Greenland?

Greenland‘s majestic ice sheet is undergoing major changes due to changes in the climatic conditions. It’s mile-thick ice sheet annually loses about 270 billion tons of ice.

The peak summer melt sends over 300,000 gallons (1,200 cubic meters) of freshwater into the sea, particularly from glaciers like Jakobshavn.

This freshwater meets the saltwater below, creating turbulent plumes.

NASA scientists believe meltwater from glaciers acts like an elevator, lifting crucial nutrients like iron and nitrate from the deep ocean to the sunlit surface.

As per NASA, this process boosts the growth of tiny, plant-like organisms called phytoplankton.

However, directly observing this process in Greenland’s remote and icy coastal waters is incredibly challenging.

“We were faced with this classic problem of trying to understand a system that is so remote and buried beneath ice. We needed a gem of a computer model to help,” said Dustin Carroll, an oceanographer at San José State University affiliated with JPL.

Supercomputers and the math of melting ice

The model ECCO-Darwin, which stands for Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean-Darwin, was used to study remote ocean areas.

To solve the massive mathematical problem of simulating how biology, chemistry, and physics interact in a fjord, scientists built a “model within a model within a model.”

The focus was on a single turbulent fjord at the foot of the Jakobshavn Glacier, the most active on the ice sheet.

The team used NASA supercomputers to simulate glacial runoff.

It was calculated that the nutrients carried upward by glacial meltwater could increase summertime phytoplankton growth in the study area by a substantial 15% to 40%.

This finding helps to explain why previous satellite data showed a 57% surge in phytoplankton growth in Arctic waters between 1998 and 2018.

In fact, on June 16, 2024, NASA’s Aqua satellite captured an image of a large phytoplankton bloom in the North Atlantic Ocean. Reportedly, about 800 kilometers wide, the bloom was located east of Greenland and south of Iceland.

Phytoplankton, though smaller than a pinhead, are vital to the planet and the ocean’s food web. These organisms absorb carbon dioxide and feed krill and other small animals, making food for larger creatures like fish and whales.

Scientists are unsure whether this boost in phytoplankton will have a long-term positive effect on marine life and fisheries.

With Greenland’s ice melt projected to accelerate, its effects on the ecosystem—from sea level to the salinity of coastal waters—are still being untangled.

The study team plans to expand its simulations to understand the impact along the Greenland coast and beyond.

The findings were reported in the journal Nature Communications: Earth & Environment.

FAQs

How big is the Greenland Ice Sheet?

Greenland’s ice sheet spans 1.7 million square kilometers, with an average thickness of 2.3 kilometers (1.4 miles), and contains 7% of the world’s freshwater.

What animals live in Greenland?

Greenland’s wildlife includes several well-known Arctic animals like the polar bear, musk ox, Arctic fox, and reindeer, although the number of land mammals is small.