Participant characteristics

A total of 147 medical oncologists completed the survey, corresponding to approximately 11% of the estimated 1340 medical oncologists practicing in Türkiye [4]. The median age of participants was 39 years (IQR: 35–46), and 63.3% were male. Respondents had a median of 14 years (IQR: 10–22) of medical experience and a median of 5 years (IQR: 2–14) specifically in oncology. Nearly half (47.6%) practiced in university hospitals, followed by 31.3% in training and research hospitals, and the remainder in private or state settings (Table 1). In terms of academic rank, residents/fellows constituted 38.1%, specialists 22.4%, professors 21.1%, associate professors 16.3%, and assistant professors 2.0%. Respondents were distributed across various urban centers, including major cities such as Istanbul and Ankara, as well as smaller provinces, reflecting a broad regional representation of Türkiye’s oncology workforce.

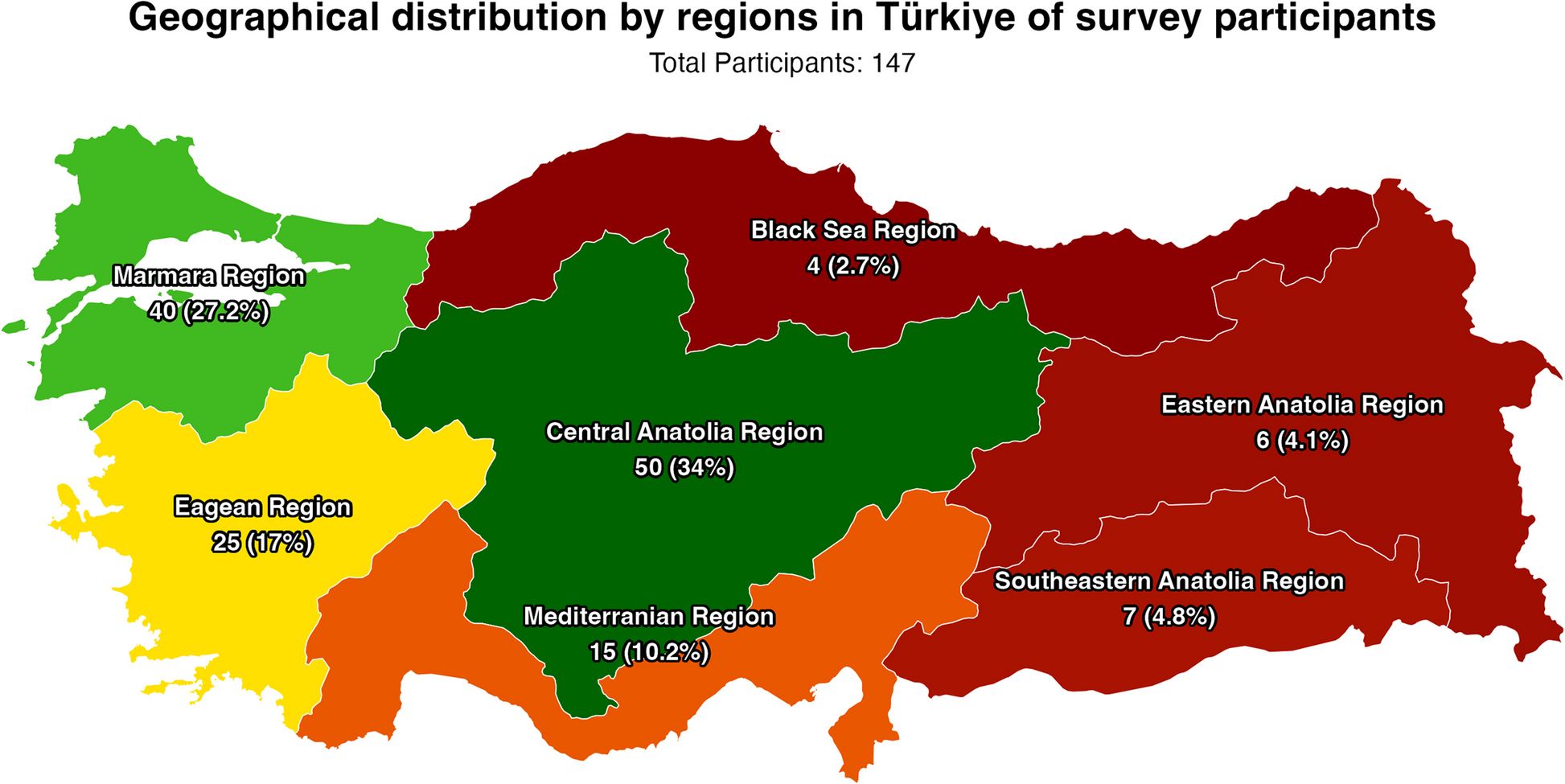

Most of the participants completed the survey from Central Anatolia Region of Türkiye (34.0%, n = 50), followed by Marmara Region (27.2%, n = 40), Eagean Region (17.0%, n = 25) and Mediterranian Region (10.2%, n = 15). The distrubution of the participants with regional map of Türkiye is presented in Fig. 1.

Geographical Distribution of Participants by Regions of Türkiye

AI usage and education

A majority (77.5%, n = 114) of oncologists reported prior use of at least one AI tool. Among these, ChatGPT and other GPT-based models were the most frequently used (77.5%, n = 114), indicating that LLM interfaces had already penetrated clinical professionals’ workflow to some extent. Other tools such as Google Gemini (17.0%, n = 25) and Microsoft Bing (10.9%, n = 16) showed more limited utilization, and just a small fraction had tried less common platforms like Anthropic Claude, Meta Llama-3, or Hugging Face. Despite this relatively high usage rate of general AI tools, formal AI education was scarce: only 9.5% (n = 14) of respondents had received some level of formal AI training, and this was primarily basic-level. Nearly all (94.6%, n = 139) expressed a desire for more education, suggesting that their forays into AI usage had been largely self-directed and that there was a perceived need for structured, professionally guided learning.

Regarding sources of AI knowledge, 38.8% (n = 57) reported not using any resource, underscoring a gap in continuing education. Among those who did seek information, the most common channels were colleagues (26.5%, n = 39) and academic publications (23.1%), followed by online courses/websites (21.8%, n = 32), popular science publications (19.7%, n = 29), and professional conferences/workshops (18.4%, n = 27). This pattern suggests that while some clinicians attempt to inform themselves about AI through peer discussions or scientific literature, many remain unconnected to formalized educational pathways or comprehensive training programs.

Self-assessed AI knowledge

Participants generally rated themselves as having limited knowledge across key AI domains (Fig. 2A). More than half reported having “no knowledge” or only “some knowledge” in areas such as machine learning (86.4%, n = 127, combined) and deep learning (89.1%, n = 131, combined). Even fundamental concepts like LLM sand generative AI were unfamiliar to a substantial portion of respondents. For instance, nearly half (47.6%, n = 70) had no knowledge of LLMs, and two-thirds (66.0%, n = 97) had no knowledge of generative AI. Similar trends were observed for natural language processing and advanced statistical analyses, reflecting a widespread lack of confidence and familiarity with the technical underpinnings of AI beyond superficial usage.

Overview of Oncologists’ AI Familiarity, Attitudes, and Perceived Impact. (A) Distribution of participants’ self-assessed AI knowledge, (B) attitudes toward AI in various medical practice areas, and (C) insights into AI’s broader impact on medical practice

Attitudes toward AI integration in oncology

When asked to evaluate AI’s role in various clinical tasks (Fig. 2B), respondents generally displayed cautious optimism. Prognosis estimation stood out as one of the areas where AI received the strongest endorsement, with a clear majority rating it as “positive” or “very positive.” A similar pattern emerged for medical research, where nearly three-quarters of respondents recognized AI’s potential in academic field. In contrast, opinions on treatment planning and patient follow-up were more mixed, with a considerable proportion adopting a neutral stance. Diagnosis and clinical decision support still garnered predominantly positive views, though some participants expressed reservations, possibly reflecting concerns about reliability, validation, and the interpretability of AI-driven recommendations.

Broadening the perspective, Fig. 2C illustrates how participants viewed AI’s impact on aspects like patient-physician relationships, social perception, and health policy. While most believed AI could improve overall medical practices and potentially reduce workload, many worried it might affect the quality of personal interactions with patients or shape public trust in uncertain ways. Approximately half recognized potential benefits for healthcare access, but some remained neutral or skeptical, perhaps concerned that technology might not equally benefit all patient populations or could inadvertently exacerbate existing disparities.

Ethical and regulatory concerns

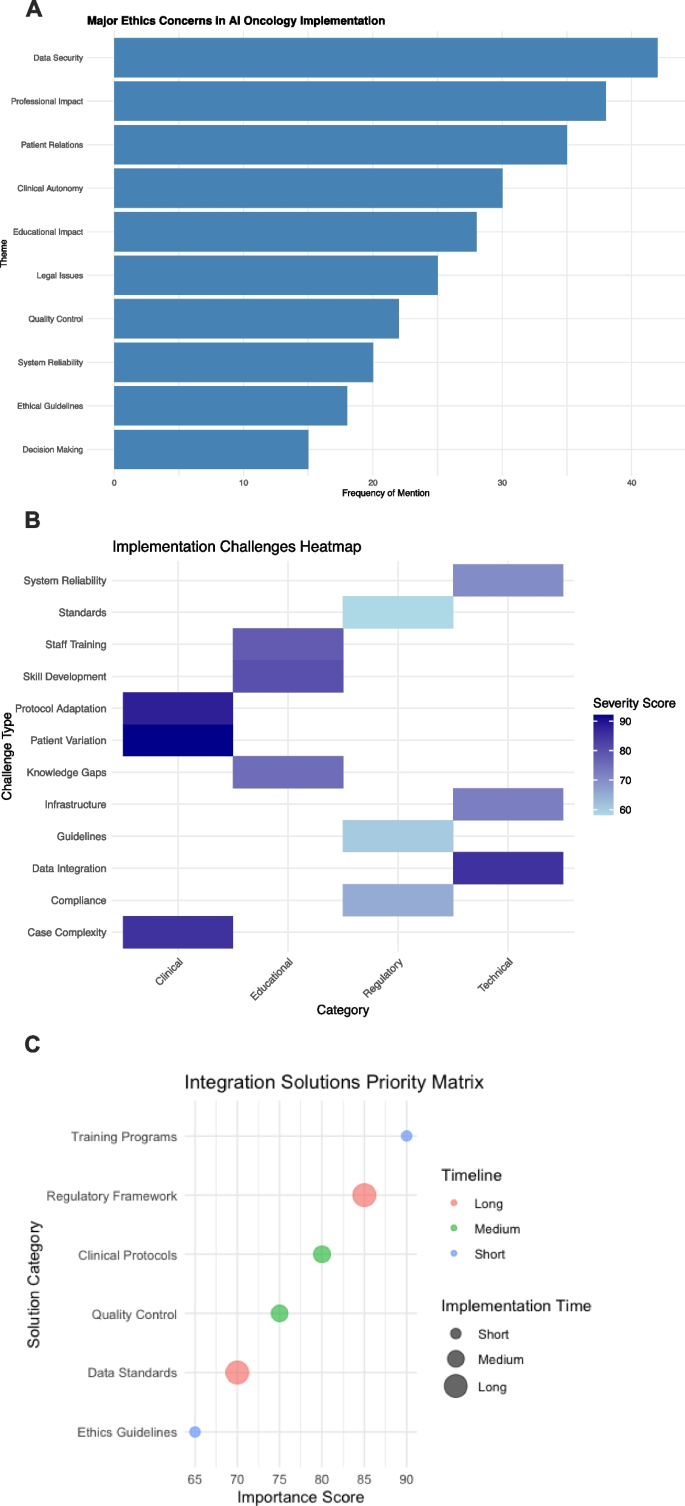

Tables 2 and 3, along with Figs. 3A–C, summarize participants’ ethical and legal considerations. Patient management (57.8%, n = 85), article or presentation writing (51.0%, n = 75), and study design (25.2%, n = 37) emerged as key activities where the integration of AI was viewed as ethically questionable. Respondents feared that relying on AI for sensitive clinical decisions or academic tasks could compromise patient safety, authenticity, or scientific integrity. A subset of respondents reported utilizing AI in certain domains, including 13.6% (n = 20) for article and presentation writing, and 11.6% (n = 17) for patient management, despite acknowledging potential ethical issues in the preceding question. However, only about half of the respondents who admitted using AI for patient management identified this as an ethical concern. This discrepancy suggests that while oncologists harbor concerns, convenience or lack of guidance may still drive them to experiment with AI applications.

Ethical Considerations, Implementation Barriers, and Strategic Solutions for AI Integration. (A) Frequency distribution of major ethical concerns, (B) heatmap of implementation challenges across technical, educational, clinical, and regulatory categories, and (C) priority matrix of proposed integration solutions including training and regulatory frameworks. The implementation time and time-line is extracted from the open-ended questions. Timeline: The estimated time needed for implementation; Implementation time: The urgency of implementation. The timelime and implementation time is fully correlated (R.2 = 1.0)

Moreover, nearly 82% of participants supported using AI in medical practice, yet 79.6% (n = 117) did not find current legal regulations satisfactory. Over two-thirds advocated for stricter legal frameworks and ethical audits. Patient consent was highlighted by 61.9% (n = 91) as a critical step, implying that clinicians want transparent processes that safeguard patient rights and maintain trust. Liability in the event of AI-driven errors also remained contentious: 68.0% (n = 100) held software developers partially responsible, and 61.2% (n = 90) also implicated physicians. This suggests a shared accountability model might be needed, involving multiple stakeholders across the healthcare and technology sectors.

To address these gaps, respondents proposed various solutions. Establishing national and international standards (82.3%, n = 121) and enacting new laws (59.2%, n = 87) were seen as pivotal. More than half favored creating dedicated institutions for AI oversight (53.7%, n = 79) and integrating informed consent clauses related to AI use (53.1%, n = 78) into patient forms. These collective views point to a strong desire among oncologists for a structured, legally sound environment in which AI tools are developed, tested, and implemented responsibly.

Ordinal regression analysis of factors associated with AI knowledge, attitudes, and concerns

For knowledge levels, the ordinal regression model identified formal AI education as the sole significant predictor (ß = 30.534, SE = 0.6404, p < 0.001). In contrast, other predictors such as age (ß = −0.1835, p = 0.159), years as physician (ß = 0.0936, p = 0.425), years in oncology (ß = 0.0270, p = 0.719), and academic rank showed no significant associations with knowledge levels in the ordinal model.

The ordinal regression for concern levels revealed no significant predictors among demographic factors, professional experience, academic status, AI education, nor current knowledge levels (p > 0.05) were associated with the ordinal progression of ethical and practical concerns.

For attitudes toward AI integration, the ordinal regression identified two significant predictors. Those willing to receive AI education showed progression toward more positive attitudes (ß = 13.143, SE = 0.6688, p = 0.049), and actual receipt of AI education also predicted progression toward more positive attitudes (ß = 12.928, SE = 0.6565, p = 0.049). Additionally, higher knowledge levels showed a trend toward more positive attitudes in the ordinal model although not significant (ß = 0.3899, SE = 0.2009, p = 0.052).

Table 4 presents the ordinal regression analyses examining predictors of AI knowledge levels, concerns, and attitudes among Turkish medical oncologists.

Qualitative insights

The open-ended responses, analyzed qualitatively, revealed several recurring themes reinforcing the quantitative findings. Participants frequently stressed the importance of human oversight, emphasizing that AI should complement rather than replace clinical expertise, judgment, and empathy. Data security and privacy emerged as central concerns, with some respondents worrying that insufficient safeguards could lead to breaches of patient confidentiality. Others highlighted the challenge of ensuring that AI tools maintain cultural and social sensitivity in diverse patient populations. Calls for incremental, well-regulated implementation of AI were common, as was the suggestion that education and ongoing professional development would be essential to ensuring clinicians use AI effectively and ethically.

In essence, while there is broad acknowledgment that AI holds promise for enhancing oncology practice, respondents also recognize the need for clear ethical standards, solid regulatory frameworks, comprehensive training, and thoughtful integration strategies. oncology care.