Confidentiality

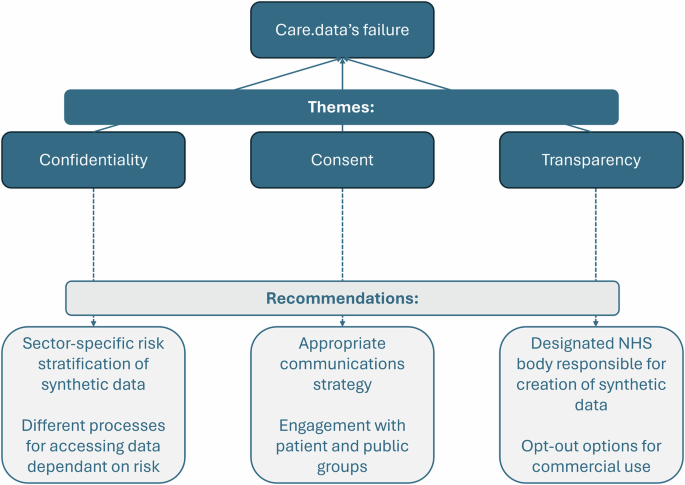

The risk of breaching patient confidentiality through re-identification became a key tenet that opponents of care.data, including medConfidential, built their opposition on despite its legality10. Although pseudo-anonymisation removes identifiers from data, there remains a risk of re-identification. Due to this, pseudo-anonymised data is bound by UK General Data Protection Regulation laws that apply to personal data11. Furthermore, aside from public stakeholders, professional groups, such as the British Medical Association (BMA) and RCGP also raised concerns about the impact of confidentiality concerns on the patient-doctor relationship and how this would negatively impact patient care. NHS England’s failure to reassure the public and professional bodies that the risk of re-identification was low enough to warrant data sharing contributed to the abandonment of care.data. Although synthetic data differs from pseudo-anonymised real-world data, both have risks of re-identification and therefore confidentiality is a critical consideration for synthetic data policy.

Utilising privacy metrics to differentiate synthetic datasets into different risk categories (e.g., low, medium and high) would help policymakers adequately mitigate for risks, and act to reassure public and professional bodies regarding reidentification risk. Set thresholds of privacy risk should be agreed to at a national level by cross-functional teams, bridging technical knowledge with sector-specific insights, led by the relevant government department. Low-fidelity data has the lowest risk of re-identification, and would require much less stringent requirements than current NHS data access processes, allowing for greater data sharing without compromising privacy. For example, as part of an NHS pilot, low-fidelity synthetic data made from Hospital Episode Statistics aggregate data is currently publicly available to download12. Medium risk synthetic datasets have a higher re-identification risk and could therefore utilise additional safeguards, such as Trusted Research Environments (TREs). This type of risk stratification also serves as a design criterion for generating organisations as if TREs cannot be supported, then low-fidelity synthetic data would be prioritised for generation. For synthetic datasets with the highest re-identification risks, identical processes needed for real-world data access should be followed. Given this, organisations who need high-fidelity synthetic data may instead choose to focus on real-world data acquisition, as the requirements for access would be the same.

Consent

A significant critique of care.data surrounded the failure of adequately consenting patients in a move that was seen by many as a violation of patient autonomy13,14. Strategies suggested by NHS England to obtain informed consent included posters to be displayed at GP practices and leaflets posted to homes15. The obvious issue with these includes assumptions that they will be read, as well as exclusionary impacts on patients for whom written text is not accessible (i.e., language barrier, literacy levels). Furthermore, the circulated unaddressed leaflets were often mistaken for junk, and households who opted out of junk mail deliveries were missed altogether16. Of those that did receive and read the leaflet, it was fedback that there was no mention of care.data by name and a lack of detailed risk information, including the possibility of re-identification, as well as details of opting-out16.

For synthetic data efforts to be successful, public acceptance is key. Although data sharing initiatives may be lawful, legal authority does not always equate to social legitimacy17. Carter et al17 explore this further, arguing that data sharing initiatives rely on a ‘social contract’ that requires trust and transparency in managing data, so that patients continue to consent to its use for research. Patients must understand what synthetic data is, both the risks and the benefits and their rights as data subjects. Without proper provision of information, synthetic data initiatives are likely to face contestation similarly to care.data, because of a breakdown in the social contract necessary for data-sharing initiatives to succeed. Therefore, meaningful engagement with Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement groups should be prioritised by policymakers.

Transparency

A significant critique that contributed to the abandonment of care.data centred on the backlash from the lack of transparency about who would be able to access data15. In response to these concerns, the Care Act 2014 was amended to prohibit data release to certain commercial companies (i.e., marketing and insurance)10. Although research has shown that public concern about commercial use of health data reduces when conditions are applied, such as data access requests having a clear public benefit, care.data’s clarifications came too late18. More recently, NHS plans for data sharing through a federated learning platform have also faced obstacles, largely due to the controversy surrounding the award of a contract to Palantir, a multibillion-dollar US tech company19.

In light of care.data’s transparency failures, synthetic data initiatives must clearly communicate to patients who the intended users are prior to roll out. To safeguard the interests of patients and garner trust, external organisations that request access to medium and high fidelity synthetic data should also go through a process where their rationale for data use is vetted to ensure it is for public benefit. Furthermore, patients should be able to opt out of synthetic data generation from their real data, with the ability to choose if commercial entities should be given access. This would help ease concerns amongst individuals who oppose commercial access, respecting patient autonomy and allowing patient choice.

In response to the current federated learning controversies stemming from NHS England awarding Palantir a £480 million contract to create and run the platform, synthetic data initiatives must be transparent in who is creating the data19. A designated public body within the NHS would be best served to have ownership of creating and managing access to synthetic data, in a move that would reassure the public and avoid the current controversies seen amongst other privacy-enhancing technology (PET) initiatives. Where outsourcing is necessary, conflicts of interest must be properly considered and published to ensure partners are considered trustworthy when managing sensitive data. For example, the openSAFELY federated platform, a publicly funded collaborative project, has gained support from the BMA, RCGP, and medConfidential, highlighting that trust in the same technology can be eroded depending on who is managing that platform20.

In summary, synthetic data offers promise in solving issues of data availability and imbalance when developing AI models. For synthetic data initiatives to be successful in a UK context, lessons from previous endeavours, such as care.data must be learned by prioritising patient confidentiality, consent and organisational transparency, with the ultimate aim of improving patient care.